America’s First True Feminist

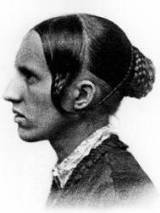

Author, editor, and journalist, Margaret Fuller (1810–1850) holds a distinctive place in the cultural life of the American Renaissance. Literary critic, editor, author, political activist and women’s rights advocate – she was also the first full-time American female book reviewer in journalism. Her book Woman in the Nineteenth Century is considered the first major feminist work in the United States. Her death at sea was a tragedy for her family and colleagues, and the loss of her many talents to womankind, then and now, is immeasurable.

Childhood and Early Years

On May 23, 1810, Sarah Margaret Fuller was the first-born child of Margarett Crane and Timothy Fuller, Jr. of Cambridgeport, Massachusetts. A lawyer and a Republican in Federalist New England, Timothy Fuller was elected to the Massachusetts Senate in 1813 and in 1818 began the first of four terms in the United States Congress, finally retiring to write. Eight daughters and sons were born to the couple, and six grew to adulthood.

After a younger sister died, Margaret was an only child and the focus of her parents’ attention until she was five. Determined to give his daughter the best possible education, her father taught her himself. Margaret remembered:

I was put at once under discipline of considerable severity, and, at the same time, had a more than ordinarily high standard presented to me… [My father] thought to gain time, by bringing forward the intellect as early as possible. Thus I had tasks given me, as many and various as the hours would allow, and on subjects beyond my age; with the additional disadvantge of reciting to him in the evening.

Margaret seemed a sponge for many disciplines, including Latin, begun at age six, English grammar, mathematics, history, music and modern languages. Margaret herself thought the price paid for this early and intensive drilling, sometimes late into the night, was sleeplessness and nightmares as a child and a lifetime of poor eyesight and migraine headaches.

On an irregular basis between 1819 and 1825, Margaret attended the Cambridge Port Private Grammar School, Dr. Park’s Boston Lyceum, and Miss Prescott’s Young Ladies’ Seminary, where her parents hoped she would gain polish in feminine accomplishments. Early instruction and natural brilliance gave her a sense of superiority which classmates interpreted as arrogance. Longing for admiration and companionship, Margaret was socially awkward and unpopular among peers who responded to her with a mixture of awe and ridicule. When her schooling ended, she pursued her studies on her own.

Her ardent spirit and astonishing accomplishments appealed to several young collegians who soon became her intimates. Eliza Farrar, wife of Harvard professor John Farrar, took Margaret on as a project in the improvement of dress and manners and introduced her to visitors like Fanny Kemble and Harriet Martineau. A cluster of girl friends completed a happy social circle as Margaret came into her own in her late teens and early twenties.

In 1833 Timothy Fuller moved his family to a farm in Groton, Massachusetts, where Margaret resented her isolation but set to work on serious writing. She published essays in Boston papers and in the Western Messenger. Her father’s sudden death of cholera in the fall of 1835 threw the family into financial crisis. Margaret struggled to protect her mother’s interests and see to the education and welfare of the younger children. From that time forward, financial difficulties plagued her life.

Fuller was invited to visit Ralph Waldo Emerson and his wife Lydian in Concord, Massachusetts in 1836. Through the Emersons, Fuller met Bronson Alcott, and the innovative educator offered her a job at his Temple School in Boston, which she accepted. But Alcott was soon forced to close his school. The following year she took a teaching position at the Greene Street School in Providence.

In 1839 Fuller moved her family from the Groton farm to a rented house in Jamaica Plain, five miles from Boston. In Elizabeth Peabody’s bookshop, Fuller held several series of Conversations for women of the surrounding area. Women had little opportunity to use their knowledge, and Fuller provided a setting where they could discuss what they knew, free to explore ideas and speak their own thoughts on many topics.

So popular were the subscriptions to these discussions and so spellbinding a conversationalist was Fuller, that she attracted not only the wives of prominent citizens, but also other sympathetic social reformers. The circle included Lydian Emerson, Sarah Ripley, Lydia Maria Child, Elizabeth Hoar, Sophia Peabody (soon to be Hawthorne) and Lydia (Mrs. Theodore) Parker.

Margaret Fuller would engage the participants in discussion before expounding her own views with a clarity of thought and expression that dazzled her listeners. That women could have their own opinions on matters outside their “sphere” proved an intoxicating proposition. These events were very successful and supported Fuller for five years (1839-1844), during which she published her acclaimed translation of Eckermann’s Conversations with Goethe and several shorter pieces.

Literary Career

In 1840 Fuller and Emerson founded The Dial, a literary and philosophical journal for which she wrote many articles and reviews on art and literature. Fuller served as editor for the first two years, working with authors such as Ellen Sturgis Hooper, Caroline Sturgis, Henry David Thoreau, Elizabeth Peabody, and George and Sophia Ripley. Fuller turned editing duties over to Emerson in 1842.

In 1843 The Dial published Fuller’s ground-breaking feminist manifesto, “The Great Lawsuit,” in which she called for women’s equality. She argued that women should be given the freedom to develop to their fullest potential, to approach the ideal, Woman. The result, she hoped, would be wholesale transformation of a society deformed by an imbalance between masculine and feminine principles.

In 1843 Margaret Fuller traveled by train, steamboat, carriage, and on foot to make a roughly circular tour of the Great Lakes. From Niagara Falls to Mackinac Island, west to Milwaukee, south to Pawpaw, Illinois, and back to Buffalo, New York – her journey covered what was then considered the far western frontier in mid-nineteenth-century America.

In 1844, she published Summer on the Lakes, in 1843, her first original book-length work, the product of her Great Lakes trip. In the book she discusses Chicago in some detail, especially lamenting the injustices suffered by Native Americans. Fuller also comments on the difficulties of frontier life for women and on the degradation of the natural environment by industrialization and settlement.

After The Dial ceased publication in 1844, Margaret Fuller moved to New York and joined Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune as literary critic, becoming the first full-time book reviewer in journalism and, by 1846, was the publication’s first female editor. Fuller worked for Greeley, boarding for a time with him and his wife, before moving to a place of her own. The period proved to be one of personal, as well as intellectual growth in Fuller’s life. During her four years with the publication, she published more than 250 columns.

In 1845 Fuller enlarged her Dial essay The Great Lawsuit and published it as Woman in the Nineteenth Century, which became a classic of feminist thought. On finishing it, she described to William Henry Channing “a delightful glow as if I had put a good deal of my true life in it, as if, suppose I went away now, the measure of my foot-print would be left on the earth.”

Woman in the Nineteenth Century revealed Fuller’s enormous knowledge of literature and philosophy as she described the oppression of the female sex through history and advocated equal status for women. Years later Horace Greeley wrote:

If not the clearest and most logical, it was the loftiest and most commanding assertion yet made of the right of Woman to be regarded and treated as an independent, intelligent, rational being, entitled to an equal voice in framing and modifying the laws she is required to obey, and in controlling and disposing of the property she has inherited or aided to acquire… hers is the ablest, bravest, broadest assertion yet made of what are termed Woman’s Rights.

During this time she also engaged in what was likely her first romantic liaison – revealed only years after her death with the publication of her letters to James Nathan – but she increased her awareness of urban poverty and strengthened her commitment to social justice and to the causes that concerned her: prison reform, abolitionism, women’s suffrage and educational and political equality.

In 1846 Fuller sailed for Europe as the first female foreign correspondent for the Tribune. In England she was introduced to Giuseppe Mazzini, the leader of the Italian Unification Movement, she soon embraced the cause of Italian freedom. After traveling in England and France, she settled in Rome in 1847.

No longer the “outsider” she had seemed in New England, she felt at home in Italy, free to express her fullest sense of self. When war broke out, she saw a role for herself “either as actor or historian.” To her the revolution meant freedom and human rights for the laboring class and for women. She sent vivid eyewitness reports to the Tribune.

Fuller also fell in love with one of Mazzini’s lieutenants, the handsome twenty-six-year-old Marchese Giovanni Ossoli, who had been disinherited by his family because of his support for Mazzini. Then in her late thirties, Fuller had survived several unfulfilled love relationships. She enjoyed the attentions of this young man in what soon became a serious attachment.

In the summer of 1848, she retreated to the village of Rieti where her son, Angelo Eugene Philip Ossoli, was born on September 7. It is not clear whether Fuller and Ossoli ever married. The couple were very secretive about their relationship but, after Angelino suffered an unnamed illness, they became closer. Fuller’s letters home had made only oblique references to her personal situation.

Finally, in 1849, she sent a letter to her mother, telling of Ossoli and the birth of their son. The letter explained that she had kept silent so as not to upset her “but it has become necessary, on account of the child, for us to live publicly and permanently together.” Her mother’s response makes it clear that she was aware that a legal marriage had not taken place. Even so, she was happy for her daughter, writing: “I send my first kiss with my fervent blessing to my grandson.”

The couple supported Giuseppe Mazzini’s revolution for the establishment of a Roman Republic in 1849 – Ossoli fought in the struggle while Fuller volunteered at a supporting hospital. Fuller used her experiences to write a book about the history of the Italian Revolution. Although the revolution at first succeeded, Fuller was right in predicting that it would not last. When the pope was restored to power, the Ossoli and Fuller fled to Florence.

There for the first time they lived together openly and were readily accepted by the expatriate colony, including the Brownings, whose baby son was close to theirs in age. Fuller continued to work on her Italian history. For a time she thought of remaining in Italy where they could live inexpensively and she could complete her book. Friends urged her to stay there, uncertain of her reception at home in her new role.

Nevertheless, Ossoli and Fuller decided to return to America with their son. They set sail from Livorno on May 17, 1850. Not long after leaving port, the ship’s captain died of smallpox, and his less competent replacement ran the ship aground less than 100 yards from Fire Island, New York, in the early morning hours of July 19, 1850. Some crew members managed to reach shore, but wind and high surf made it impossible to launch a lifeboat. The ship slowly sank, and Fuller drowned at age 40.

Henry David Thoreau went to search the wreckage, but no trace was found of their bodies or personal effects, including Fuller’s manuscript history of the Italian revolution. A memorial to Fuller was erected on the beach at Fire Island in 1901 through the efforts of Julia Ward Howe. The Fuller family erected a monument to Margaret in their plot at Mount Auburn cemetery in Cambridge.

Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote of Margaret Fuller:

She wore [her] circle of friends, when I first knew her, as a necklace of diamonds about her neck. They were so much to each other that Margaret seemed to represent them all, and to know her was to acquire a place with them. The confidences given her were their best, and she held them to them. She was an active, inspiring companion and correspondent, and all the art, the thought, the nobleness in New England seemed at that moment related to her and she to it.

Margaret Fuller’s major work, Woman in the Nineteenth Century, published in 1845, profoundly affected the women’s rights movement which had its formal beginning at the first Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, New York three years later. Fuller “possessed more influence on the thought of American women than any woman previous to her time.” So wrote Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton in their 1881 History of Woman Suffrage.

SOURCES

PBS.org: Margaret Fuller

Wikipedia: Margaret Fuller

Margaret Fuller’s Summer on the Lakes

Unitarian and Universalist Biography: Margaret Fuller