Wife of Declaration Signer John Hancock

Dorothy Quincy Hancock Portrait

John Singleton Copley, Artist, 1772

Copley posed Dorothy with a hand to her face in a thoughtful pose. Her silk pink robe and matching stomacher are decorated by a large bow, and the sleeves end in triple ruffles. Her sheer apron is embroidered with large floral sprays. Her hair was probably combed over a roll, and atop this hairdo she wore a dress cap of lace, gauze and ribbon.

Dorothy Quincy, born in Boston on May 10, 1747, was the youngest of ten children of Judge Edmund Quincy and Elizabeth Wendell Quincy. Dorothy spent most of her early years in Braintree, Massachusetts, in a lively household, where John and Samuel Adams, Dr. Joseph Warren, James Otis, and John Hancock frequently visited her father, an ardent patriot. Dorothy was raised at the Quincy Homestead in what is now Quincy, Massachusetts.

Dorothy’s mother was Elizabeth Wendell, daughter of Abraham and Katharine DeKay Wendell of New York, an educated and accomplished woman of high character, with a taste for social life and a liking for the society of young people. Therefore, the Quincy household, with its bevy of handsome girls, had many visitors. After she entered her teens, Dorothy Quincy must have heard alot about patriotism.

John Hancock was born on January 23, 1737, at Braintree, Massachusetts, in a part of town which eventually became the separate city of Quincy. He was the son of a Congregational pastor, and as a young child, Hancock lived a comfortable life.

In 1744, upon the death of his father, the 7-year-old boy came to live with his grandfather, the Reverend John Hancock, at Lexington, Massachusetts, where he spent the next six years. In 1750, he was taken in by his childless uncle Thomas Hancock and his wife Lydia, who lived in Hancock Manor, a looming two-story granite mansion on Beacon Hill. There he became the focus of his Aunt Lydia’s attentions, “the object of her fondest affection on this side of heaven.”

Thomas Hancock owned a firm known as the House of Hancock, which imported manufactured goods from Britain and exported rum, whale oil and fish. His highly successful business made him one of Boston’s richest and best-known residents. The couple became the dominant influence on John’s life.

John was sent to Boston Latin School, then for a business education at Harvard College, where he graduated at the age of seventeen. He then went on to apprentice in Uncle Thomas’ commercial empire, and greatly pleased the old gentleman by his intelligence and attention to his duties. John learned much about his uncle’s shipping business during these years, and was trained for eventual partnership in the firm. Hancock worked hard, but he also enjoyed playing the role of a wealthy aristocrat, and developed a fondness for expensive clothes.

In 1760, John went to England for a year while building relationships with customers and suppliers. Here he had a chance to supplement his education with travel and acquaintance with men of affairs. He listened to the debates of Parliament, witnessed the funeral of George II and the coronation of George III, and picked up a good general knowledge of the English people and their way of thinking.

Back in Boston, John gradually took over the House of Hancock as his uncle’s health failed, becoming a full partner in January 1763. When Thomas Hancock died in August 1764, John inherited the business, Hancock Manor, and thousands of acres of land. John Hancock, at the age of twenty-seven, was one of the wealthiest men of Massachusetts. This placed him in a society of men who consisted mainly of loyalists.

After its victory in the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763), the British Empire was deep in debt, and for the first time Parliament decided to directly tax the colonies, beginning with the Sugar Act of 1764. The act provoked outrage in Boston, where it was widely viewed as a violation of colonial rights, because the colonists had no representation in Parliament, and could not be taxed by that body. Americans, who for 160 years faithfully paid taxes to their respective colonial governments, were, for the first time, expected to pay this additional tax direct¬ly to Great Britain.

Hancock soon became involved in revolutionary politics and his sentiments were for independence from Great Britain. From that time, he began closing out his commercial interests and devoting himself more and more to public affairs. His first office was that of selectman of the town of Boston. In 1766, John Hancock was elected to the General Assembly, having as colleagues such patriotic men as John and Samuel Adams, James Otis, and Thomas Cushing.

Hancock’s political success benefited from the support of Samuel Adams, the clerk of the House of Representatives and a leader of Boston’s popular party, also known as Whigs and later as Patriots. The two men made an unlikely pair. Fifteen years older than Hancock, Adams had a somber, Puritan outlook that stood in marked contrast to Hancock’s taste for luxury and extravagance. Historian William Fowler, who wrote biographies of both men, characterized the relationship between the two as symbiotic, with Adams as the mentor and Hancock the protégé.

Hancock’s popularity grew with everyone except Royal Governor Sir Francis Barnard and his official clique, who held Hancock and Samuel Adams responsible for the constantly growing spirit of opposition to the acts of King and Parliament.

Royal Governor Francis Barnard offered Hancock a commission as Lieutenant in the militia. Hancock, knowing that it was a covert attempt at bribing him, tore up the commission in the presence of many prominent citizens. Consequently when Hancock was elected Speaker of the Assembly in 1767, the Governor vetoed the selection.

At the opening of the next session of the Assembly, Hancock was again elected Speaker, and again it was vetoed. Then he was elected a member of the Executive Council, and that was also denied by the Governor. All this only endeared Hancock to the people. Few figures were more well known or more popular than John Hancock.

Dorothy’s father, Judge Edmund Quincy was an earnest patriot, and their home was the gathering place for such men as the Adamses, Dr. Joseph Warren, James Otis, and others of their rebellious group. John Hancock was a welcome visitor at the Quincy home.

In 1768, Hancock’s sloop Liberty was impounded by customs officials at Boston Harbor, on a charge of running contraband goods. A large group of private citizens stormed the customs post, burned the government boat, and beat the officers, causing them to seek refuge on a ship off shore.

Even more trouble followed Parliament’s passage of the 1773 Tea Act. On November 5, Hancock was elected as moderator at a Boston town meeting that resolved that anyone who supported the Tea Act was an “Enemy to America.” Hancock and others tried to force the resignation of the agents who had been appointed to receive the tea shipments. Unsuccessful in this, they attempted to prevent the tea from being unloaded after three tea ships had arrived in Boston Harbor.

Hancock was at the fateful meeting on December 16, 1773, where he reportedly told the crowd, “Let every man do what is right in his own eyes.” Hancock did not take part in the Boston Tea Party that night, but he approved of the action, although he was careful not to publicly praise the destruction of private property.

Over the next few months, Hancock was disabled by gout, which would trouble him with increasing frequency in the coming years. By March 5, 1774, he had recovered enough to deliver the fourth annual Massacre Day oration, a commemoration of the Boston Massacre of 1770. Hancock’s speech denounced the presence of British troops in Boston, who he said had been sent there “to enforce obedience to acts of Parliament, which neither God nor man ever empowered them to make”. The speech, probably written by Hancock in collaboration with Adams, Joseph Warren, and others, was published and widely reprinted, enhancing Hancock’s stature as a leading Patriot.

During the years immediately preceding the beginning of the Revolutionary War, the British Government constantly watched Hancock and Samuel Adams. They were regarded as dangerous men, who could not be frightened, bribed, nor cajoled.

Parliament responded to the Tea Party with the Boston Port Act, which closed the Port of Boston on March 30, 1774. This was one of the so-called Coercive Acts intended to strengthen British control of the colonies. Royal Governor Thomas Hutchinson was replaced by General Thomas Gage, who arrived in May 1774.

On June 17, 1774, the Massachusetts House elected five delegates to send to the First in Philadelphia, which was being organized to coordinate colonial response to the Coercive Acts.

In October 1774, Gage canceled the scheduled meeting of the General Court. In response, the House resolved itself into the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, a body independent of British control. Hancock was elected as president of the Provincial Congress and was a key member of the Committee of Safety. Under Hancock, they created the first companies of minutemen – soldiers who pledged to be ready for battle at a moment’s notice.

On December 1, 1774, the Provincial Congress elected Hancock as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress. Before Hancock reported to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, the Provincial Congress reelected him as their president.

After attending the Provincial Congress in Concord, Massachusetts, in April 1775, John Hancock and Samuel Adams decided that it was not safe to return to Boston. They expected to be arrested at any time if their whereabouts were known. They decided to stay instead at the church parsonage in Lexington, John Hancock’s childhood home, now the home of his brother-in-law, Reverend Jonas Clarke.

Dorothy Quincy had lost her mother in 1769, and Lydia Hancock, John Hancock’s aunt, had taken Dorothy under her wing. Early in 1775, Judge Quincy was called away from home on business, and Dorothy, left alone in their Boston home, accepted an invitation from Aunt Lydia to pay her a visit at Lexington, where she was staying at the Clarke house.

On the evening of April 18, 1775, Hancock and Adams were also guests of Reverend and Mrs. Clarke, and eight of the twelve Clarke children. Clarke had encouraged the Revolutionaries to use his home as a meeting place and refuge. During the period leading up to the Revolutionary War, his inspiring sermons were a source of inspiration to the citizens of Lexington during the crisis with Britain.

At this time, British General Thomas Gage ordered Hancock and Adams arrested for treason. Through their spies, the British authorities had learned where Hancock and Adams were staying, and it was arranged to take them into custody at the Hancock-Clarke house.

On the night of April 18, 1775, an expedition numbering over 800 Redcoats left Boston, crossed the Charles River in boats, and in the early morning hours of April 19, set out for the small farming town of Lexington eleven miles away.

Around midnight, after everyone had gone to bed, Paul Revere galloped up to the house, which he found guarded by eight men under a sergeant who halted him. “The regulars are coming out!” exclaimed the excited Revere. “Ring the bell!” ordered Hancock from a second-story window, and the bell soon began pealing and continued all night.

Early the next morning, John and Dorothy were forced to part in great haste. By daybreak, one hundred and fifty men had mustered for the defense of the town. Hancock was ready to join the Patriot militia at Lexington, but Adams and others convinced him to avoid battle, arguing that he was more valuable as a political leader than as a soldier. They went back through the rear of the house and garden to a thickly wooded hill where they could watch the progress of events.

At dawn, on Lexington Common, Captain John Parker had gathered a small group of militiamen, numbering about seventy, when the British Regulars arrived. Major John Pitcairn of the Royal Marines commanded the Redcoat advance, and believing the militiamen constituted a threat to his flank, ordered them to lay down their arms. Realizing the impossibility of their situation, Captain Parker ordered a retreat.

At that point a shot rang out. Who fired first has never been established. However, the Regulars responded with two crushing volleys, killing eight and wounding nine militiamen. The retreating men of Lexington managed to fire only a few scattered shots wounding one Redcoat and grazing Major Pitcairn’s horse. Although over quickly, this small engagement would have a lasting and dramatic effect. The Revolutionary War had begun.

Dorothy and Aunt Lydia had remained in the house, and were eyewitnesses of the first battle of the Revolution. Dorothy watched from her bedroom window, and wrote: “Two men are being brought into the house. One, whose head has been grazed by a ball, insisted that he was dead, but the other, who was shot through the arm, behaved better.”

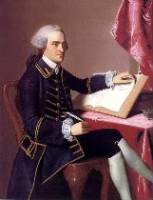

John Hancock Portrait

By John Singleton Copley, c. 1765

Following the Battle of Lexington, Gage issued a proclamation was issued granting a general pardon to all who would “lay down their arms, and return to the duties of peaceable subjects” – except Hancock and Adams. Singling out Hancock and Adams in this manner only added to their renown among Patriots.

A few hours later, Adams and Hancock fled northward to Burlington, Massachusetts. They later moved from place to place, before proceeding to Philadelphia to attend the Continental Congress, which convened the next month.

For a time, Hancock and Adams remained in seclusion to avoid being arrested by General Gage, who intended to have them sent to England for trial. A few days later, Dorothy and Aunt Lydia traveled to Fairfield, Connecticut, where they were guests of Reverend Thaddeus Burr, a leading citizen.

The first word concerning Hancock’s whereabouts during the interim between his escape from Lexington and his arrival at the Continental Congress, appointed to convene at Philadelphia, May 10, 1775, is contained in a long letter to Miss Quincy. This letter gives a rather elaborate account of the dangers and triumphs of his journey.

On May 24, 1775, Hancock was elected the third President of the Second Continental Congress, succeeding Peyton Randolph.

Hancock’s nickname for his fiancee was Dolly. In spite of his many duties as President of the Continental Congress and his other public responsibilities, he wrote to Dorothy frequently when they were separated, always with affection and respect, and in nearly all of his letters he complained because she did not write to him.

On June 10, 1775, Dorothy, still at Fairfield, received this letter from John:

MY DEAR DOLLY: – I am almost prevail’d on to think that my letters to my Aunt and you are not read, for I cannot obtain a reply, I have ask’d million questions and not an answer to one, I beg’ d you to let me know what things my Aunt wanted, and you and many other matters I wanted to know, but not one word in answer. I Really Take it extreme unkind, pray, my dear, use not so much Ceremony and Reservedness, why can’t you use freedom in writing, be not afraid of me, I want long Letters…

John Hancock and Dorothy Quincy were married on August 28, 1775, by Reverend Burr in Fairfield, Connecticut. Two children were born to the Hancocks: Lydia Henchman Hancock, who died when she was ten months old, and John George Washington Hancock, who fell on the ice while skating and died shortly after, at the age of nine, in 1787.

They left at once for Philadelphia, arriving September 5, 1775, where John lived at intervals during the remainder of the session of the Continental Congress. Dorothy seems to have spent much of her time in Boston during that time.

![]()

Signature On the Declaration of Independence

Hancock was president of Congress when the Declaration of Independence was adopted and signed. Hancock and the other delegates signed the official copy of the Declaration on August 2, 1776. On the document proclaiming America’s independence, Hancock’s name is inscribed boldly with flourishes, the mark of a confident, proud man. According to popular legend, Hancock signed his name largely and clearly to be sure King George III could read it without his spectacles, causing his name to become an eponym for signature in the United States.

In October 1777, after more than two years in Congress, Hancock requested a leave of absence due to problems with gout. By this time, Hancock had become estranged from Samuel Adams, who disapproved of what he viewed as Hancock’s vanity and extravagance, which Adams believed were inappropriate in a republican leader. When Congress voted to thank Hancock for his service, Adams and the other Massachusetts delegates voted against the resolution, as did a few delegates from other states.

Back in Boston, Hancock was reelected to the House of Representatives. As in previous years, his philanthropy made him popular. Although his finances had suffered greatly because of the war, he gave to the poor, helped support widows and orphans, and loaned money to friends. In December 1777, he was re-elected as a delegate to the Continental Congress and as moderator of the Boston town meeting.

Hancock rejoined the Continental Congress in Pennsylvania in June 1778, but his brief time there was unhappy. In his absence, Congress had elected Henry Laurens as its new president, which was a disappointment to Hancock, who had hoped to reclaim his chair. On July 9, 1778, Hancock and the other Massachusetts delegates joined the representatives from seven other states in signing the Articles of Confederation; the remaining states were not yet prepared to sign, and the Articles would not be ratified until 1781.

After much delay, the new Massachusetts Constitution finally went into effect in October 1780. To no one’s surprise, Hancock was elected Governor of Massachusetts in a landslide, winning over 90% of the vote. He governed Massachusetts through the end of the Revolutionary War and into an economically troubled postwar period. Hancock avoided controversial issues as much as possible.

Hancock was easily re-elected to annual terms as governor, until his surprise resignation on January 29, 1785. Hancock cited his failing health as the reason, but he may also have been aware of growing unrest in the countryside and wanted to get out of office before the trouble came. The turmoil that Hancock avoided became known as Shays’ Rebellion, which Hancock’s successor had to deal with. After the uprising, Hancock was reelected in 1787, and he promptly pardoned all the rebels. Hancock was reelected to annual terms as governor until his death.

In 1787, delegates met at the Philadelphia Convention and drafted the United States Constitution, which was then sent to the states for ratification or rejection. Hancock, who was not present at the Convention, had misgivings about the new Constitution’s lack of a bill of rights and its shift of power to a central government. In January 1788, Hancock was elected president of the Massachusetts ratifying convention, although he was ill and not present when the convention began.

Hancock mostly remained silent during the contentious debates, but as the convention was drawing to close, he gave a speech in favor of ratification. For the first time in years, Samuel Adams supported Hancock’s position. Even with the support of Hancock and Adams, the Massachusetts convention narrowly ratified the Constitution by a vote of 187 to 168. Hancock’s support was probably a deciding factor.

Hancock was named as a candidate in the 1789 U.S. presidential election. As was the custom in an era where political ambition was viewed with suspicion, Hancock did not campaign or even publicly express interest in the office. Like everyone else, Hancock knew that George Washington was going to be elected as the first president, but Hancock may have been interested in being vice president, despite his poor health. Hancock received only four electoral votes in the election, however, none of them from his home state; the Massachusetts electors all voted for another native son, John Adams, who became the vice president. Hancock was disappointed with his poor showing, but he remained as popular as ever in Massachusetts.

His health failing, Hancock spent his final few years as essentially a figurehead governor.

John Hancock died on October 8, 1793, at the age of fifty-six, with Dorothy at his side. By order of acting governor Samuel Adams, the day of Hancock’s burial was a state holiday. His lavish funeral was perhaps the grandest given to an American up to that time.

Hancock was a vain, flamboyant man, who lived in princely splendor on Boston’s Beacon Hill. Nonetheless, he was a devoted patriot. He risked his fortune in the struggle for independence and performed valuable services for his country. John Adams referred to him as an “essential character” of the American Revolution.

In 1796, Dorothy remarried to Captain James Scott, who had been employed by Hancock as a captain in his trading ventures with England. They lived in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and had no children together.

When Captain Scott died, Dorothy moved back to the Hancock Mansion at 30 Beacon Street in Boston for about ten years, and later lived at 4 Federal Street in Boston.

Dorothy Quincy Hancock died February 3, 1830.

SOURCES

First Shot

John Hancock

Dorothy Quincy

The Freedom Trail

Hancock’s Dorothy Q

John Hancock Biography

Dorothy Quincy Hancock

Wikipedia: John Hancock

XIV Men Of The Revolution

Biography of John Hancock

American Revolution Home Page

1776 President of the Continental Congress