American Patriot

Image: Hannah Winthrop by John Singleton Copley, 1773

Copley was America’s foremost painter of the 18th century. This portrait represents Copley at the height of his power and exhibits the intensive realism that was the principal characteristic of his work at that time. Copley rendered the varying textures of her muslin cap, silk dress and lace cuffs with remarkable precision. In painting the beautifully reflective tabletop upon which she rests her hands, he demonstrated a degree of technical competence equaled by few of his contemporaries.

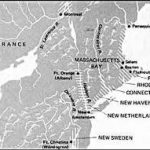

Hannah Fayerweather was the daughter of Thomas and Hannah Waldo Fayerweather, whose descendants came to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630. Although her exact birth date is not known, she was baptized at the First Church of Boston on February 12, 1727.

In 1745, Hannah married Parr Tolman, who died young. In 1756, she married John Winthrop, a great-great-grandson of the John Winthrop who founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Hannah and John Winthrop lived in Cambridge, where her husband was professor of mathematics and natural history at Harvard College and a noted astronomer. The family lived at 93 Mt. Auburn Street, facing the market square that is now called Winthrop Square. Hannah provided a lively account of her life in Cambridge in a series of letters to Mercy Otis Warren and Abigail Adams.

John Winthrop was actively interested in public affairs, was a judge of probate in Middlesex County for several years, was a member of the Governor’s Council in 1773-74, and subsequently gave the weight of his influence to the patriotic cause in the Revolution.

In the mid-18th century, Cambridge was only a village. About 800 people lived within the present city limits, most of them near Harvard Square. What set Cambridge apart was Harvard College, one of only a dozen such institutions in British America. As the oldest and most prestigious, it attracted students from throughout the colonies.

The majority of the town’s residents were descendants of the early Puritan settlers. They worked as farmers, artisans, or tradespeople, worshiped in the Congregational church, and relied on local resources for their livelihoods. Many would fight for independence from British rule.

A smaller group of wealthy families lived on sizeable estates in the village. Some also owned sugar plantations in Jamaica and Antigua in the Caribbean. These families were all members of the Anglican parish of Christ Church, and in the coming conflict would support the Crown. Adversaries labeled them Tories or Loyalists.

Cambridge voters spoke out at an early date against the taxes imposed upon them by the British Parliament. At least two Cambridge residents, John Hicks and Joshua Wyeth, participated in the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773. As punishment, Parliament abolished most elected officials in Massachusetts and replaced them with those appointed by the king.

During the period of the American Revolution, John Winthrop enthusiastically promoted the colonial cause, encouraged munitions production, and advised George Washington and other American leaders.

The Revolutionary War

As April 1775 approached, rumors abounded in eastern Massachusetts: the British army’s next target would be the gunpowder and supplies stored in Concord; John Hancock and Samuel Adams, the patriot leaders who were staying in Lexington, would be arrested.

By Tuesday April 18, 1775, the British were ready to act. After nightfall, the two lanterns burning in the belfry of Boston’s Old North Church alerted Paul Revere and other watchers that the British soldiers (called redcoats or regulars) would arrive by water. Two men rode out of Boston that night to alert Hancock and Adams in Lexington: Paul Revere and William Dawes, who had an hour’s march on Revere.

Later that night, the regulars rowed from Boston Common across the Charles River to present East Cambridge. About 2:00 am, the redcoats finally began to march down today’s Gore Street. At 5:00 am, the first shots of the Revolutionary War were exchanged on Lexington Green. A second engagement took place four hours later at Concord’s North Bridge.

Word of the fighting at Lexington and Concord spread quickly. Some of the Cambridge militia marched toward Lexington; others readied an ambush at Harvard Square to await the redcoats’ return. Hannah Winthrop described the scene in a letter to a friend:

Not knowing what the event would be at Cambridge at the return of these bloody ruffians, and seeing another brigade dispatched to the assistance of the former, looking with the ferocity of barbarians, it seemed necessary to retire to some place of safety till the calamity was passed…

We were directed to a place called Fresh Pond, about a mile from the town, but what a distressed house did we find it, filled with women whose husbands had gone forth to meet the assailants, seventy or eighty of these, with numbers of infant children, weeping and agonizing for the fate of their husbands.

The War for Independence had truly begun. On the night of April 19, the provincial Committee of Safety, the overseers of colonial civil defense, met in the home of Jonathan Hastings on Cambridge Common. General Artemus Ward was chosen as the first commander-in-chief of the New England militias and selected Hastings’ house as his headquarters.

Within days, more than 20,000 armed men from all over New England had gathered in Cambridge. The Tories’ vacant estates, the empty Christ Church and even Harvard’s brick buildings served as barracks for more than 1,600 troops, officers’ quarters and hospitals. Soldiers camped on Cambridge Common in tents and other makeshift shelters. This rowdy and unkempt crew would become the core of George Washington’s new American army.

By order of the Committee of Safety, Harvard College canceled classes on May 1. Classes resumed in Concord in October 1775; the students did not return to Cambridge until June 1776. During the nine months when Harvard moved to Concord, the Winthrops occupied the house known as The Wayside.

The Wayside

Concord, Massachusetts

This house would later be the home of

Louisa May Alcott and Nathaniel Hawthorne.

On June 15, 1775, the Continental Congress in Philadelphia had appointed George Washington commander-in-chief of the army. Arriving in Cambridge on the afternoon of July 2, Washington met that evening with the New England generals at Hastings’ house. The next day he took command of the army and visited the troops at their lines in Cambridge and Roxbury.

As the colonial fight for independence from the mother country ensued, Abigail Adams was appointed by the Massachusetts Colony General Court in 1775, along with Mercy Otis Warren and Hannah Winthrop to question their fellow Massachusetts women, who were charged by their word or action of remaining loyal to the British crown and working against the independence movement.

Hannah Winthrop letter to Mercy Warren:

August 17,1775

Dear Mrs. Warren, the Friend And Sister Of My Heart,

What a great Consolation is it that tho the restless ambition and unbounded Avarice and wicked machinations of some Original Characters have deprived us of many of the pleasures of life yet are they not able to take from us the heartfelt Satisfaction of mutual affection and Friendly Converse. Your Favor Truly Delineates human nature in a disagreeable light. The Contrast is very striking!What have we to expect from such Vitiated Persons as you present to view in the British Generals. I hope their Wicked inclinations will be restrained. I am Charmed with the Portrait you give of General Washington. Must not we expect Success under the direction of so much goodness.

But my heart Bleeds for the people of Boston, my blood boils with resentment at the Treatment they have met with from Gage. Can anything equal his Barbarity. Turning the poor out of Town without any Support, those persons who were possessed of any means of Support stopped and Searched, not suffered to carry anything with them.

Can anything equal the distress of parents Separated from their Children, the tender husband detained in Cruel Captivity from the Wife of his Bosom, she torn with anxiety in fearful looking for and expectation of Vengeance from the obdurate heart of a Tyrant supported by wicked advisers?

General Washington wrote that he expected to leave Cambridge by autumn, but as the stalemate with the British dragged on into the winter, he sent for his family. Martha Washington, her son and his wife arrived in Cambridge on December 11, 1775, and remained here until the army’s departure in April 1776.

Hannah Winthrop Letter to Mercy Warren:

January 14, 1777

I think a New Year presents a brighter View. I congratulate you on our late Success, let us my friend enjoy this Victory, and tho a Skilful General has been meanly kidnapped let us not think the Fate of America hangs on the Prowess of a single person.

My son William received a letter last night from an officer of distinguished rank in the army who writes The Scale is turned greatly in our Favor. The enemy are intimidated and fleeing before them and says if we had but 5000 Continental Troops he makes no doubt they would be able to cut them all off. However, he hopes to diminish them greatly. What a pity it is to want men at so important a Crisis. He gives the N. Englanders great merit in the Late glorious Action.

Hannah Winthrop’s husband died in Cambridge on May 3, 1779. I could find no record of her death.

SOURCE

First Lady Biography: Abigail Smith Adams