Wife of Declaration Signer William Williams

Mary Trumbull was born on July 16, 1745, in Lebanon, Connecticut, the second daughter of Jonathan Trumbull, Royal Governor of Connecticut, who was the only Colonial governor to remain true to the cause of the Colonies. He served as governor in both a pre-Revolutionary colony and a post-Revolutionary state, and patriots from all parts of New England came to consult with him and lay plans for future action. Trumbull was in constant correspondence with Samuel Adams and other patriots of Massachusetts, and the confidant and adviser of General Washington.

Mary Trumbull was also the sister of patriots Jonathan, Jr. and Joseph Trumbull and of the painter John Trumbull, daughter of Connecticut governor Jonathan Trumbull, (Sr.), and great-great-great-granddaughter of John Alden and Priscilla Mullins, was also a third cousin once removed of Patriots John Adams and Oliver Wolcott.

William Williams was born on April 18, 1731, in Lebanon, Connecticut, to Solomon Williams, pastor of the town’s First Congregational Church and Mary (Porter) Williams. His father and grandfather were both been ministers. At the age of sixteen, Williams entered Harvard College. During his collegiate course, he was distinguished for diligent attention to his studies and was honorably graduated with a B.A. degree from Harvard in 1751.

Williams then returned home and studied for the ministry under his father, planning to follow his father and grandfather into the ministry. Although he was a very religious man, and served as a church deacon for 43 years, Williams decided not to become a minister.

After about a year, Williams enlisted in the Continental Army and joined his uncle, Colonel Ephraim Williams, in the French and Indian War on his expedition to Lake George. On September 8, 1755, his uncle was leading 1200 men when he was ambushed by the enemy, and at the first volley, was shot through the head.

After the war, Williams opened a store in his hometown of Lebanon. He prospered as a merchant and entered politics. As was common in those days, Williams held several posts at the same time. At age 21, he was elected town clerk of Lebanon, a post he would hold for forty-four years. He also served as a selectman of Lebanon for twenty-seven years, as a member of the Connecticut legislature‘s Lower House for twenty years, the Upper House for twenty-three years, and as a judge for thirty-five years.

On February 14, 1771, Mary Trumbull married William Williams, and allied himself with one of the most prominent and influential families in the colony. Mary was twenty-five years old at the time of their marriage, a handsome, educated, and accomplished young woman. Williams took his bride to a handsome home not far from the big house of his father-in-law, which was to be known during the Revolution as the “War Office.” Three children were born to Mary Williams and her husband: Solomon, born January 6, 1775; Faith, born September 29, 1774; and William T., born March 2, 1779.

As troubles began with Britain, Williams wrote letters to newspapers complaining of British injustice. A man of naturally ardent temper, he threw himself vehemently into the struggle for independence, wielding a vigorous pen and drawing generously on his purse in support of military activities. Williams became colonel of the 12th regiment of militia in 1773.

In June 1776, delegate Oliver Wolcott had to leave the Continental Congress due to illness. Williams resigned his commission in the militia to replace Wolcott. He closed his business, leaving himself entirely free to attend to public affairs. And in all these actions, he was loyally supported by his wife whose patriotism was equal to his own.

More than most women of her time, Mary Trumbull Williams understood the condition of affairs leading up to the American Revolution, and it must have been a proud day when her husband was elected a delegate to Congress. Her public-spirited husband, who had for years watched the gradual encroachment on the rights of the colonists by the British; through his association with British officers during the French and Indian War, had come to know the contempt in which they held the Colonies and their rights.

Williams arrived in Philadelphia on July 28, 1776, too late for the vote for independence, but he signed the Declaration of Independence with other delegates on August 2. He would remain in Congress for just over a year and a half, from 1776 to 1778, but during this time, he helped to frame the Articles of Confederation. Williams also served as a delegate to the Congress of the Confederation in 1783 and 1784.

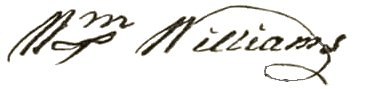

William Williams Signature

On the Declaration of Independence

At a meeting of the Council of Safety in Lebanon, CT, near the close of 1776, when the prospects of the colonies’ success looked dark, two members of the Council were invited to Mr. and Mrs. Williams’ home, Benjamin Huntington and William Hillhouse. The conversation touched on the gloomy outlook. Mr. Hillhouse expressed hope and confidence. “If we fail,” said Mr. Williams, “I know what my fate will be. I have done much to prosecute the war; and one thing I have done which the British will never pardon. I have signed the Declaration of Independence; I shall be hanged.”

During a great part of the Revolutionary War, Williams was a member of the Council of Safety, and sacrificed nearly all his property to the patriot cause. He purchased supplies for the army with his own money, went from house to house soliciting private donations, and made frequent speeches to induce a larger enlistment.

Throughout the war, the Williams house was open to American soldiers in their marches to and from the army. During the winter of 1781, Mary and William gave up their house to the officers of a detachment of soldiers stationed near them, and took other quarters for themselves.

In January 1788, Connecticut held a convention to decide whether or not to approve the proposed US Constitution. Lebanon sent Williams to the convention with instructions to vote against adopting the new Convention. Convinced that the new framework would help the country, Williams instead voted to accept the US Constitution, and on January 9, 1788, Connecticut became the fifth state to approve the Constitution.

In 1804, Williams declined re-election to the Connecticut Assembly, and withdrew entirely from public life. His life and fortune were both devoted to his country, and he had earned the love and veneration of his countrymen.

The death of his son Solomon in 1810 was a great blow to Williams; it shocked his already infirm constitution, and he never recovered from it. His health gradually declined; and a short time bfore his death he was overcome with stupor. After laying perfectly silent for four days, he suddenly called upon his departed son to attend his dying father in the world of spirits, and then expired.

William Williams died on August 2, 1811 in Lebanon, CT, at the age of 80, exactly 35 years to the day that he signed the Declaration of Independence. His grave is in the Trumbull Cemetery, about a mile northeast of town.

Mary Trumbull Williams died in February 1831, in Lebanon, CT, at the age of 86.

William and Mary Trumbull Williams Gravesite

Trumbull Cemetery

Lebanon, CT

SOURCES

Mary Trumbull Williams

William Williams 1731 – 1811

Signer of the Declaration of Independence

William Williams: Connecticut