Abducted by Indians in Pennsylvania

Frances Slocum, or Maconaquah, (1773-1847) was an Indian captive who was taken from her family home in Pennsylvania in 1778 by the Delaware Tribe. She was raised by an elderly Miami Indian couple in what is now Ohio and Indiana. Slocum was reunited with her white relatives in 1838, but remained with her adopted Native American family for the rest of her life.

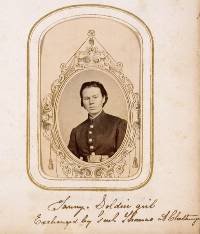

Image: The austere woman portrayed in this painting by artist John Froehlich is much less Frances Slocum and far more Maconaquah.

Childhood and Early Years

Frances Slocum was one of ten children born to Jonathan and Ruth Tripp Slocum, a Quaker family who emigrated from Rhode Island to the Wyoming Valley of Pennsylvania in 1777. During the Revolutionary War, the Slocums remained in the settlement while many others fled before the Battle of Wyoming in July 1778. During that battle British forces and Seneca warriors destroyed a nearby fort and killed over 300 American settlers.

The Slocums believed that their Quaker pacifist beliefs and friendly relations with the local natives would protect them. However, on November 2, 1778, Frances Slocum was taken captive at the family farm near Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. The first night after her abduction was spent in a crude shelter under a rock ledge along Abraham Creek, where Frances tried to escape, but was soon recaptured.

For many years the Slocum family searched far and wide for Frances. Before her death Ruth Slocum begged her sons to never stop looking for their lost sister. The brothers made many long and dangerous journeys and spent thousands of dollars, but the time went by and they could not find her.

Frances Slocum was traded for animal pelts to a childless Miami couple, who named her Maconaquah, or Young Bear. She adapted very well to the Indian way of life, and was much loved by her new parents. In 1779 the Continental Army burned their crops and drove Maconaquah and her Indian family from their land. They moved west and settled in Kekionga, present day Fort Wayne, Indiana.

As Maconaquah grew older she became a celebrity of sorts within her Indian community. She was known not only for her light skin and flaming red hair, but also for excelling at the foot races and games on horseback played by the Indian braves. According to the people in her community, Maconaquah grew to be a very beautiful young woman.

In 1790 she married a young Delaware man named Tuck Horse and moved into a wigwam with Tuck Horse and his family. It was cramped, crowded, and allowed no privacy for the young couple to get acquainted. She was very disappointed when it became apparent that Tuck Horse had no plans to leave his family or build his own home.

Before long, with her mother-in-law in agreement, Maconaquah began gathering materials to build their own home and wove together the reeds for it. Other problems began to arise in the marriage. Tuck Horse left her alone while he went on long hunting trips, and spent all their earnings on whiskey and frivolous trinkets instead of necessities. When his drinking led to domestic violence, Maconaquah returned to live with her adoptive parents.

Marriage and Family

While walking through the woods one day Maconaquah found a man who had been injured in battle, whom she learned was a Miami brave named Shepoconah. She took the man to her parents’ home and nursed him back to health. He began helping to run the household as he regained his strength. Before Maconaquah’s father died, he thanked Shepoconah for his help and gave Maconaquah to him for his wife.

Shepoconah, Maconaquah and her mother then moved to live with his people along the banks of the Mississinewa River near Peru, Indiana, where they were very happy together. Shepoconah later became Chief of the Miami Indians in the area. Maconaquah gave birth four children, two sons who died at a young age and two daughters who survived to adulthood.

Shepoconah was a large, heavy set man and a great warrior, with headquarters at the Osage village near the mouth of the Mississinewa River. After Shepoconah lost his hearing he gave up his duties as Chief. He moved farther up the river and built a large log house and established a trading post nine miles above Peru, Indiana. There a settlement grew up that became known as Deaf Man’s Village.

These wealthy Indians had a standard of living that far excelled that of the early white man in the area. Deaf Man’s Village became a social center for whites and Indians. Shepoconah died in 1833 and was buried on a knoll a few hundred yards from his dwelling. By 1835 the Miami and Potawatomi Indians in the area had sold most of their property to the whites.

In 1835 Colonel George Ewing, an Indian trader who did business with the Miami and spoke their language fluently, stayed the night at a log cabin in Deaf Man’s Village. There he spoke with an elderly Miami woman who was now a widow, living with her extended family in a double log cabin. Living with her were her two daughters, a son-in-law named Jean Baptiste Brouillette and her three grandchildren. This was Maconaquah.

Although Deaf Man’s Village attracted a mix of European and Native culture because of the lucrative fur trade, Maconaquah was thoroughly a member of the Miami tribe, still practicing traditions and ceremonies that had not changed much from the century before. Ewing was intrigued by her uncharacteristically light skin, and asked about her background.

Fifty-seven years after her abduction, Maconaquah revealed to George Ewing that she was white by birth. On January 20, 1835, Ewing recounted Maconaquah’s story in a letter to the postmaster of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Mary Dickson, who was also the publisher of the local newspaper Lancaster Intelligencer. It was not until two years later that the paper’s new owner John W. Forney found the letter.

In August 1837, Forney published Ewing’s letter in the Lancaster Intelligencer, asking if anyone had a relative taken by the Indians during the Revolutionary War:

There is now living in this place among the Miami Tribe of Indians, an aged white woman, who, a few days ago told me that she was taken away from her father’s house on or near the Susquehanna River when she was very young. She says her father’s name was Slocum, that he was a Quaker and wore a large-brimmed hat.

The Reunion

After learning about the woman who might be his long lost sister, Isaac Slocum came to Peru, Indiana in May 1838 and visited Maconaquah’s home at Deaf Man’s Village. To Isaac she looked like a perfect Indian, but he had a foolproof test of her identity. Before Frances had been abducted her brother Ebenezer had crushed the forefinger of her left hand with a hammer. When Isaac looked at the old woman’s left hand, he saw a scar. When asked what caused the injury she responded, “My brother struck it with a hammer a long time ago.”

The two talked for hours through an interpreter – Maconaquah did not speak English. When his brother and sister, Joseph Slocum and Mary Town, arrived, the three visited Maconaquah again. She treated them with kindness, but was always quiet and unmoved – Native Americans are known for their stoic nature. Some months later they visited her again, bringing some of their children to meet Frances and her descendants.

Later Years

During the ensuing years, Maconaquah became reacquainted with her white family and grew attached to them. They urged her to return to Pennsylvania with them, but she replied:

I do not wish to live any better, or anywhere else, and I think the Great Spirit has permitted me to live so long because I have always lived with the Indians. I should have died sooner if I had left them. On his dying bed my husband charged me not to leave the Indians. I have a house and large lands, two daughters, a son-in-law, three grand children, and everything to make me comfortable; why should I go, and be like a fish out of water?”

After the news spread that the Lost Sister of Wyoming had been found, the story of Frances Slocum became well known. The Slocum family hired European artist George Winter to paint a portrait of Frances. Winter wrote descriptions of the Miami Indians, Dead Man’s Village, and Maconaquah and her family in his journals. This is Winter’s description of Maconaquah as she posed for the protrait he painted of her in 1839:

Frances Slocum’s face bore the marks of deep-seated lines. The muscles of her cheeks were like corded rises, and her forehead ran in almost right angular lines. There was indication of no unwanted cares upon her countenance beyond time’s influence which peculiarly marks the decline of life.

She bore the impress of old age, without its extreme feebleness. Her hair which was evidently of dark brown color was now frosted. Though bearing some resemblance to her family, yet her cheek bones seemed to bear the Indian characteristic in that particular – face broad, nose somewhat bulby, mouth perhaps indicating some degree of severity. In her ears she wore some few ‘ear bobs.’

An 1840 treaty between the Miami and the United States government stated that the Indians had to leave their homeland within five years. By 1845 they were being threatened with forced removal to Kansas. With the help of her brothers, Maconaquah appealed to the U.S. Congress, asking to be exempted from the treaty.

In 1845 a bill was introduced in Congress which provided that the one mile square (640 acres) of land then occupied by the Miami Indians and including the house and improvements of Frances Slocum, should be granted to her and her heirs forever. After John Quincy Adams eloquently defended her case in Congress, the bill became law and Maconaquah and twenty-one of her Miami relatives were allowed to remain in Indiana.

Maconaquah Frances Slocum died at her Indian home on March 9, 1847 at age 74, and was buried next to her husband and two small sons in the cemetery next to her cabin.

An oral tradition by Chief Clarence Godfroy, the great-great-grandson of Maconaquah, was later written down, which told a story of a woman who was revered by the Miami community, especially after her husband died. Members of the community often went to her for council. She also enjoyed breaking ponies and playing games alongside the men. While this behavior would have been shocking in an American pioneer setting, it was not uncommon for women to have these roles within the Miami tribe.

On May 6, 1900 her descendants, both white and Indian, raised a monument at her gravesite that still stands today in Indiana’s Mississinewa Lake region, near the Frances Slocum State Recreational Area and Lost Sister Trail. The zinc marker on her monument is a tribute to her life as both Maconaquah and Frances Slocum, as well as to her husband, who is commemorated on one side.

SOURCES

Frances Slocum

Wikipedia: Frances Slocum

WikiMarion: Frances Slocum – A Legend

My Adopted Dad is one of her descendents. It attracted my interest when faced the prospect of writing a paper. So I decided I would try to write a paper on the forced removal of the Miami and leaps people to honor them

I am also one of her descendants…….She is my great great great great grandmother!! This article is so interesting!!

I’m not a relative but I grew up in Slocum’s Grove, Casnovia Twp, Muskegon Co., MI where her brother’s grandson, Giles Bryan Slocum, owned over 6 sections of land & timber and supposedly built a sawmill on Crockery Creek’s north branch. I grew up on 200 acres with 2 miles of the creek running through it learning to fish in that creek & riding my horses like the wind over the 200 acres. Best childhood ever!!

Very interesting article. I grew up to the east of Slocum Grove. My dad owns the property that sawmill sat on. Part of the damn is still there. You can see it to the north side of Crockery Creek on Laketon Ave.

i currently live in slocums grove on elliott rd. just learning about the area, despite living in ravenna my entire life. Interesting to see where the names of the road came from. Trying to find info on my house that was built in or around 1912. i heard it was a bar at one point. Further down the rabbit hole i’ll have the go

In the Wyoming Valley of Pennsylvania (from where she was abducted) there is a State Park that bears her name as well as a town called Maconaquah (sp).

Interesting story of how Stockholm Syndrome goes back further in time than just the 1973 bank robbery in Sweden and how the mental illness can surface in later generations who pride themselves of being descended due to it. It is strange that places are named in memorial for a woman whose only accomplishment in life was to suffer from a mental disorder.

You (Aaron) are obviously a failed and pathetic excuse for a “human being”.

Well said. He is pathetic. I am related to her brother Ebenezer and proud of our NEPA family history.

William Slocum

When children are taken at such an early age, the memories of the past fade or become very dim. She was loved and treated well by her Indian parents, the bonds grow strong, and the love of those who loved her becomes the only world they really know. I certainly don’t consider mental illness to be the case in this situation.

I think she sounds like a strong woman that persevered despite her difficult situation and made the best of it. Great informative article. Makes me proud to be a woman.

Very interesting history story. Being from Indiana for 57 years now I have heard of the name Frances Slocum but never knew the story. I enjoyed the comments by the descendants. I agree with Jack’s comment in regards to Aaron’s comment.

I would hope people would consider the history in that, anyone living on “the frontier” that was Pennsylvania in those times, were all at risk and all subject to terrors, on either side of the native or quaker/european interloper just trying to make a life. Frances Slocum was abducted around age 5 and was traded for/adopted by a native couple who had no children. They raised her as their own and named her after the father. She later married a man she was unhappy with so she was allowed to divorce him and return home to care for her eldery native parents. I don’t think Stockholm syndrome is appropriate in this situation. I think you have to do more research than this article to form a valid opinion and understanding about this particular person or even someone else’s life. I think having John Quincy Adams represent your case to be able to stay on your land while the Gov’t is relocating your community to Kansas/Trail of Tears establishes historical reverence alongside her individual contributions as a white woman and leader among the tribe which had many other “mixed/french-canadian/native” people within it. History of people is not so black and white that you can establish Stockholm syndrome to a well respected and loved figure who’s life was a catalyst to allow what is now the Miami tribe of Indiana to stay on/near their original lands/territory. I think that’s just as significant as any founding father. If you want to take her lineage back to the family of Major General Nathanael Greene, second in command to General Washington during the Revolutionary War, please do so.

I am also a descendant! Loved reading this history. We have the book, The Lost Sister.

Her parents were my Sixth Great Grandparents. All this time we thought the story of a girl being abducted by Indians was a family tale. So great to know the facts behind it

I’m also a descendent , we attended the reunion in Walbash for years. It’s a wonderful time. Learning about our heritage.