Novelist and Journalist in the New Nation

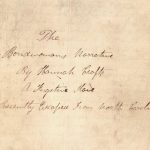

Hannah Foster (1758–1840) was an early American novelist. Her novel, The Coquette or, The History of Eliza Wharton, was published anonymously in 1797 – as written by A Lady of Massachusetts. Not only was it the first novel written by a native-born American woman, in its depiction of an intelligent and strong-willed heroine, the novel transcends many of the conventions of its time and place. It is an epistolary novel in which the plot is revealed in letters between friends and confidants.

Hannah Webster was born on September 10, 1758 in Salisbury, Massachusetts, the daughter of a wealthy merchant. Her childhood and adolescence are largely undocumented. She was sent to boarding school for several years after her mother died in 1762. The literary allusions and historical facts contained in her work indicate an outstanding education.

By 1771 young Hannah was living in Boston, where she began writing political articles for local newspapers. Her publications attracted the attention of John Foster, a graduate of Dartmouth.

In 1785 Hannah Webster married Reverend John Foster, and they settled in Brighton, Massachusetts, where Foster served as a pastor at First Parish Church. Within ten years, Hannah gave birth to six children, three sons and three daughters.

About 1790 the Fosters moved to the newly constructed and much larger First Church Parsonage at 10 Academy Hill Road, where Hannah wrote two novels. Her first novel, The Coquette or, The History of Eliza Wharton, published anonymously in 1797, was loosely based on the seduction and betrayal of Elizabeth Whitman of Hartford, Connecticut, her husband’s distant cousin, nearly a decade earlier.

The daughter of parents highly respected in clerical, political and social circles, Whitman was accomplished, vivacious, and widely admired. She is known to have been engaged to the Reverend Joseph Howe, and then later to the Reverend Joseph Buckminster, but she married neither. After rejecting those suitors, Whitman engaged in a clandestine affair that left her pregnant and abandoned.

Her seducer, it was generally believed, was Pierpont Edwards, son of the great evangelical minister Jonathan Edwards, the preacher who spearheaded the religious movement known as the Great Awakening. The high reputation of Pierpont’s father added spice to the scandal, and exerted a powerful attraction upon the reading public. Clergy such as Jonathan Edwards taught that reading novels led to moral decline.

Scandalized, Elizabeth Whitman disappeared, but in July 1788 sought lodging at the Bell Tavern in Danvers, Massachusetts. She is said to have identified herself as “Mrs. Walker” and told the innkeepers she was waiting for her husband to join her. However, while there she gave birth to a stillborn, illegitimate child and subsequently died.

Whitman’s story became public knowledge when the Salem Mercury (July 29, 1788) reported that “a female stranger” had given birth at a roadside tavern and had died. Generations of New Englanders circulated alternative accounts of Whitman’s last months. Admirers regularly made pilgrimages to her gravesite during the 19th and early 20th centuries and broke off pieces of her tombstone for souvenirs.

Elizabeth Whitman’s death at age 37 was highly publicized in many New England newspapers. The title page to The Coquette announces the tale as “A Novel Founded on Fact,” proving that the novel was based on newspaper accounts of Whitman’s death. Ministers and journalists blamed her demise on her reading of romance novels, which turned her into a coquette.

Foster’s novel offers a more sympathetic portrayal of Whitman and the social conditions that led to the downfall of an otherwise well-educated woman, as well as the restrictions placed on middle-class women in early American society. The Coquette dignified Whitman’s character by downplaying the sensationalism of the many newspaper accounts of her death.

The Coquette was one of the best-selling novels of its time and was said to have been, next to the Bible, the most popular reading material of early 19th century New England and one of the two best-selling American novels of the time. It was reprinted eight times between 1824 and 1828. However, it was not until 1866 that Hannah Foster’s name appeared on the title page.

Foster’s second work, The Boarding School; or, Lessons of a Preceptress to Her Pupils, was published in 1798. The first portion of the work is a description of the finishing school run by Mrs. Maria Williams, which includes exhortations on social conduct, reading and general preparations for survival.

The second part of the novel, containing letters from the students to the teacher and to each other, demonstrates the beneficial effects of Mrs. William’s instruction. In Foster’s day, The Boarding School may have seemed the predictable work of a minister’s wife. Today, it illuminates the gender conflicts underlying Foster’s classic, The Coquette.

Thereafter, Hannah Foster returned to newspaper writing and devoted herself to encouraging young writers, and raising a large family.

About 1810, John and Hannah built an elaborate mansion, which has been described as “a very large square house which faced to the south, to the front porch of which was added an ell used as a library and a reception room. The hilly land east of the house was terraced and the daughters became very industrious in keeping the grounds well stocked with flowering shrubs and plants.”

Prior to 1827, Reverend Foster presided over the only church in Brighton. As wife of the town’s sole minister, and the daughter of an important Boston merchant, Hannah became the acknowledged social leader of the community. A history of the Massachusetts Federation of Women’s Clubs credits her with having founded in the early 1800s the first women’s club in Massachusetts.

In 1827, a schism occurred in Brighton’s First Parish Church, when a breakaway group established the Brighton Evangelical Congregational Society. A short time later Reverend Foster, who was in his sixties and in failing health, relinquished his pulpit.

After her husband’s death in 1829, Hannah moved to Montreal, Quebec, Canada to live with her daughter, Elizabeth Foster Cushing, the wife of Dr. Frederick Cushing, who was the physician at the Emigrant Hospital there.

Pioneer novelist Hannah Foster died in Montreal in 1840, at age 81.

Two of Foster’s daughters went on to become famous writers during the 1800s. Harriet Vaughan Cheney published A Peep at the Pilgrims in 1636, Confessions of an Early Martyr, The Rivals of Acadia and Sketches from the Life of Christ. Eliza Lanesford Cushing published Esther, a dramatic poem, and works for the young. The two sisters wrote in conjunction The Sunday-School, or Village Sketches.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: The Coquette

Wikipedia: Hannah Webster Foster

Heath Anthology: Hannah Webster Foster

Hannah Foster: Brighton’s Pioneer Novelist