The Forten Women of Philadelphia

The Fortens were one of the most prominent black families in Philadelphia Pennsylvania. Wealthy sailmaker James Forten and his wife Charlotte Vandine Forten headed the family; their daughters were: Margaretta, Harriet, and Sarah. The Fortens were active abolitionists who took part in founding and financing at least six abolitionist organizations. The Forten sisters were educated in private schools and by private tutors.

Image: Sisters by Keith Mallett

Margaretta Forten (1806-1875)

Margaretta was an African American abolitionist and suffragist. She worked as a teacher for at least thirty years. During the 1840s she taught at a school run by Sarah Mapps Douglass; in 1850 she opened her own school. Margaretta never married and lived with her parents as an adult. In time, she took on the responsibility of running of her parents’ home on Lombard Street in Philadelphia, caring for her elderly mother and bachelor brothers Thomas and William.

Margaretta Forten supported the women’s rights movement, touring and giving speeches in favor of women’s suffrage, as well as helping obtain signatures for petition drives. Suffering from recurrent respiratory problems, possibly tuberculosis, she was forced to take absences from school several times, but she remained a teacher and dedicated advocate of social reform until her death from pneumonia on January 14, 1875.

Harriet Forten Purvis (1810-1875)

Harriet and her sister Sarah both married into another family of prominent black Philadelphia abolitionists, the Purvises. Harriet married Robert Purvis in 1832. The couple had eight children, but they were wealthy enough to employ a governess, enabling Harriet to accompany her husband to many anti-slavery conventions and to participate fully in the movement. In addition to raising her own children, Harriet raised her niece Charlotte Forten after her mother died in 1846.

Image: Harriet Forten Purvis

Alongside her husband, Harriet Forten Purvis was a conductor on the Underground Railroad. The household of Robert and Harriet Forten Purvis became a major haven for fugitive slaves. The Purvises also entertained many of the leading abolitionists of their day, including William Lloyd Garrison and John Greenleaf Whittier, who wrote a poem dedicated to Harriet and her sisters.

In later years, Harriet worked with the women’s suffrage movement. In her later years, Harriet lectured for black suffrage.

Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society

James Forten belonged to the American Anti-Slavery Society, which did not allow women to be members. Therefore, in December 1833 all of the Forten women and fourteen others co-founded the Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Society, the first American biracial organization of women abolitionists.

Margaretta Forten helped draft the Society’s constitution and was an officer in the organization. Harriet Forten Purvis frequently helped organize the Society’s antislavery fairs, which raised money for their various programs. Sarah Forten Purvis served on the governing board. The Forten women also represented the Society as delegates to state and national conventions.

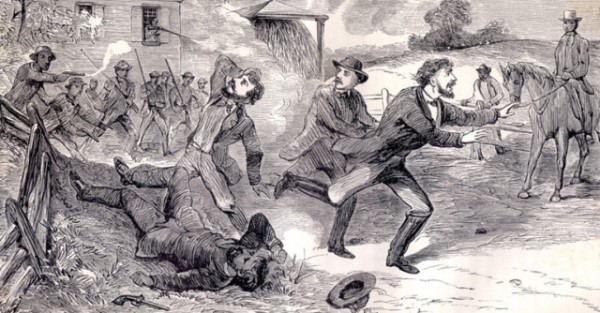

The Christiana Riot

In Christiana, Pennsylvania, a group of African Americans and white abolitionists took part in a shootout with a posse from Maryland who had come to capture four fugitive slaves hidden nearby in September 1851. In the exchange of gunfire, slave owner Edward Gorsuch was killed and two others wounded.

A manhunt was launched to find and arrest the slaves who had fled north; however, with the help of the Underground Railroad and abolitionist Frederick Douglass, the fugitives made their way to freedom in Canada.

A grand jury indicted thirty-seven African Americans and one white man on 117 counts of treason under the provisions of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law. William Deas Forten, brother of the Forten sisters, continued the family’s tradition of activism by coordinating the defense of the blacks who were charged with the death of the Southern slaveholder. Most were acquitted.

Image: Engraved illustration of the Christiana Riot

Public domain

Fugitive Slave Laws

In February 1793, Congress passed the first fugitive slave law, requiring all states, including those that forbade slavery, to forcibly return slaves who had escaped from other states to their original owners. The law stated that:

No person held to service of labor in one state, under the laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in consequence of any law or regulation therein, be discharged from such service or labor, but shall be delivered upon claim of the party to whom such service or labor may be due.

As they abolished slavery, most Northern states relaxed enforcement of the 1793 law, and many passed laws ensuring fugitive slaves a trial by jury. Several Northern states went so far as to prohibit state officials from aiding in the capture of runaway slaves. This disregard of the first fugitive slave law enraged Southerners and led to the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, which called for the return of slaves “on pain of heavy penalty.” This law required the return of all escaped slaves to their owners in the South.

Sarah Forten Purvis (1814-1883)

Born 1814 in Philadelphia, Sarah Forten Purvis was a writer, poet, and abolitionist. Starting at age 17, she wrote numerous poems and articles for William Lloyd Garrison‘s abolitionist newspaper the Liberator under the pseudonyms “Magawisca” and “Ada.” Sarah’s poems were widely read and distributed in the abolitionist movement. Black band leader Frank Johnson put her poem The Grave of the Slave (1831) to music, and it was often played at anti-slavery events.

Sarah and her sisters Margaretta and Harriet were members of the Female Literary Association, a Philadelphia based African American women’s group founded in 1831. The purpose of the Association was the “mental improvement in moral and literary pursuits” of its members. It was through these types of organizations that Sarah’s writing and speaking was nurtured.

In an 1837 letter to abolitionist Angelina Grimke, Sarah wrote:

For our own family – we have to thank a kind Providence for placing us in a situation that has hitherto prevented us from falling under the weight of this evil. We feel it but in a slight degree compared with many others. … We are not disturbed in our social relations – we never travel far from home and seldom go to public places unless quite sure that admission is free to all – therefore, we meet with none of the mortifications which might otherwise ensue.

In 1838, Sarah married Joseph Purvis, brother of Harriet’s husband Robert. They lived near Robert and Harriet’s family in Byberry near Philadelphia. When Joseph Purvis died in 1857, Sarah moved with her children to the Forten family home.

Sarah Forten Purvis’ Poem The Slave Girl’s Address to Her Mother:

Oh! mother, weep not, though our lot be hard,

And we are helpless-God will be our guard:

For He our heavenly guardian doth not sleep;

He watches o’er us-mother, do not weep.

And grieve not for that dear loved home no more;

Our sufferings and our wrongs, ah! why deplore?

For though we feel the stern oppressor’s rod,

Yet he must yield as well as we, to God.

Torn from our home, our kindred and our friends,

And in a stranger’s land, our days to end,

No heart feels for the poor, the bleeding slave;

No arm is stretched to rescue and to save.

Oh! ye who boast of Freedom’s sacred claims,

Do ye not blush to see our galling chains;

To hear that sounding word-‘that all are free’

When thousands groan in hopeless slavery?

Upon your land it is a cruel stain

Freedom, what art thou?-nothing but a name.

No more, no more! Oh God, this cannot be;

Thou to thy children’s aid wilt surely flee:

In thine own time deliverance thou wilt give,

And bid us rise from slavery, and live.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Margaretta Forten

History.com: The Christiana Riot

Sarah Forten Purvis (1814-1883)

Africans in America: The Forten Women

Encyclopedia: Margaretta Forten (1806-1875)