Conductor on the Underground Railroad

Quakers Levi and Catherine Coffin helped thousands of fugitive slaves to safety in Newport, Indiana and Cincinnati, Ohio through the Undergound Railroad, a network of more than 3,000 homes and other stations that helped runaway slaves travel from southern states to freedom in northern states and Canada.

Image: Catherine Coffin and her husband Levi

On October 28, 1824, Levi Coffin married Catherine White, sister of his brother-in-law and long-time friend. The Coffins and the Whites were Quakers and abolitionists who opposed slavery. Catherine’s family is believed to have been involved in helping runaway slaves, and it is likely she met Levi while taking part in these activities. Catherine gave birth to Jesse, the first of their six children, in 1825.

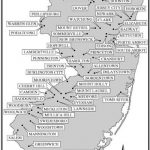

Underground Railroad in Indiana

In 1826, Levi and Catherine Coffin decided to follow Quaker family and friends who had already moved to the free state of Indiana, and made their home in Newport (now Fountain City), Indiana. Levi soon opened a successful general store and became a respected member of society. He learned that there was a large community of free blacks near Newport, where fugitive slaves hid before continuing north, but they were often recaptured because their hiding place was well known.

Coffin contacted the black community and made it known to them that he would be willing to hide runaway slaves in his home. The Coffins first took fugitive slaves into their home in the winter of 1826–1827, providing transportation, shelter and food and clothing for the runaways. Catherine made clothing for the freedom seekers, so they would be presentable as they made their way north.

Levi and Catherine Coffin became very active in the Underground Railroad, a vast network of secret routes, safe houses and hiding places. Although the term Underground Railroad did not come into use until the 1830s, the organization had been operating in Indiana since the early 1820s. The purpose of the UGRR was to transport slaves from station to station until a safe place was reached where the slave was set free.

This was dangerous work, and illegal. Article IV of the U.S. Constitution required the federal government to go after runaway slaves. The 1793 Fugitive Slave Act was the mechanism by which the government could pursue runaway slaves in any state or territory. It authorized local governments to seize and return escaped slaves to their owners and imposed penalties on anyone who aided in their flight.

The Fugitive Slave Acts were among the most controversial laws of the early 19th century. Widespread resistance to the 1793 law later led to the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which added further provisions regarding runaways and levied even harsher punishments for those interfering in their capture. If the slaves were discovered, they were returned to their masters in the South.

Many Northern states passed special legislation in an attempt to circumvent the Slave Acts. Massachusetts had abolished slavery in 1783, but the Fugitive Slave Acts required government officials to assist slavecatchers in capturing fugitives within their state. These laws were not formally repealed by an act of Congress until 1864.

Word of the Coffins’ activities quickly spread through the community of Newport. While many Quakers opposed slavery, few were willing to risk their lives and freedom to help slaves escape bondage, but many gave the Coffins money, food and clothing to be used in their work. Other locals who had been afraid now joined them, and helped to create a more formal route whereby the fugitives could be moved more easily from stop to stop.

In his later years, Levi stated that his business success had granted them the ability to become heavily involved in the Underground Railroad. Thanks to the Coffins’ generosity, courage and organizational skills, the number of fugitives escaping through eastern Indiana increased significantly.

Levi Coffin House

The Coffins had this two-story, eight-room brick home built in 1839, and several modifications were made to the it to create better hiding places. A secret door was created in the maids’ quarters where up to fourteen people could hide in a narrow pocket between the walls. Most rooms in the home have at least two ways out and many unusual hiding places, and there was an unusual indoor well in the basement, which concealed the vast amount of water necessary to sustain many guests.

Image: Levi Coffin House in Newport, Indiana, known as the Grand Central Station of the Underground Railroad.

The Coffin home became the point of convergence for three major escape routes from Madison and New Albany, Indiana, and Cincinnati, Ohio. Coffin moved the fugitives from his home to the next stop during the night. It is said that Levi and Catherine Coffin helped as many as 2,000 slaves escape to freedom in the free states and Canada during the 20 years they lived in Newport.

In the twenty years they lived in Newport, Catherine also gave birth to five more children: two girls and three boys, so there was always a baby or toddler to care for in addition to numerous houseguests.

Catherine Coffin was at the heart of the Newport railroad line. She organized a sewing society that stitched clothes for fugitives. Agents would meet ragged runaways to assess clothing needs and sizes and then choose garments from the Antislavery Sewing Society depository at the Coffin house.

Levi recalled at their fiftieth wedding anniversary party:

There never was a night too cold, or dark or rainy, for her to get up at any hour, and prepare a meal for the poor fugitives… many a time 12, 15, and even 17 sat down.

Despite death threats from slave hunters, “they were never in the least terrified.” As the years passed, the Underground Railroad activities became accepted and they had little to fear in Newport. The “conductors” were politically and financially powerful, and even those neighbors who felt no call to harbor ex-slaves, did not report fugitives to the sheriff.

Conductor Nathan Coggswell remembered transporting refugees in his ox cart north towards Canada. Most came to him from the Coffins’ organization.

When there were women and children we had to rig out a covered wagon. We sometimes hung chairs, spinning wheels and other articles on the wagon to give the outfit the appearance of movers.

During the 1840s and 1850s as national consciousness of slavery’s evils developed, the need for secrecy in eastern Indiana subsided. Coggswell described the network of friends:

I knew every person between Richmond, Indiana and Michigan who would take us in and keep us all night… We talked over the situation freely among ourselves, but said little or nothing to others. We had no signs or secret words.

In addition to the white abolitionists who aided them in their important work, the Coffins also employed the help of many blacks, such as William Bush. He was so desperate to be free that after he escaped from a plantation in the South, he walked the entire way to the Levi Coffin house in Newport. Bush stayed on until his death working as a conductor for other runaway slaves. Conductors were responsible for getting the fugitive slaves to the next station.

Pressure from the Quakers

During the 1840s pressure was brought to bear on the Quaker communities that helped escaping slaves. In 1842 Quaker leaders advised their members to cease membership in abolitionist societies and stop assisting runaway slaves. They insisted that legal emancipation was the best course of action.

The following year they disowned the Coffins and expelled them from their meeting house because they continued to be active role in assisting escaping slaves. Coffin and other Quakers who supported his activities separated and formed the Antislavery Friends. The two groups remained separate until a reunification in 1851. Despite the opposition, their desire to help the runaway slaves only increased.

Free Labor Goods

Over the years Levi came to realize that many of the goods he sold in his business were the product of slave labor. When he learned of organizations in Philadelphia and New York City that sold only goods produced by free labor, he began to purchase stock from these organizations. Free labor proponents in the east wanted to create a similar organization in the west, and approached Coffin to see if he would be interested in managing the proposed Western Free Produce Association. At first he declined.

In 1845 a group of abolitionist businessmen opened a wholesale mercantile business in Cincinnati, and the the Free Produce Association raised $3,000 to help stock the new warehouse with goods. Different groups continued to pressure Levi to accept a position as the director of the new business. Reluctantly, he finally accepted, but agreed to only oversee the warehouse for five years, in which time he could train someone else to run it.

Underground Railroad in Ohio

Long before the Civil War, Quakers urged consumers not to buy goods produced by slave labor. At a convention at Salem, Indiana, a group of Quakers funded a wholesale warehouse in Cincinnati that would handle only goods produced by free labor. Antislavery leaders requested Levi Coffin’s help in running the warehouse. Levi rented out his Newport business before leaving and made arrangements for his home to continue serving as an Underground Railroad stop.

In 1847, the Coffins moved to Cincinnati, where they continued their efforts to help fugitive slaves. Cincinnati was the center of Underground Railroad activity along the Ohio-Kentucky border. Unlike Newport, the town was divided between antislavery and proslavery activists. Refugees crossing into the city were followed by masters who enlisted the authorities to return their human property and arrest anyone who helped in their escape.

Image: The Underground Railroad by Charles Webber, 1891

Depicts Levi and Catherine Coffin helping slaves to safety.

The setting may be the Coffin home in Cincinnati.

The Coffins moved several times in the city, and finally came to reside on Wehrman Street, in a large home with rooms that were rented out for boarding. With the many guests coming and going, the home was an excellent cover for a station on the Underground Railroad. Again Catherine fed and clothed runaways during their first days of freedom, and her Cincinnati house had a larger attic than the one in Newport.

Catherine began creating costumes, and when fugitives arrived she dressed them as butlers, cooks and other household workers. The most frequently used disguise was a that of a Quaker woman. The high collar, long sleeves, gloves, veil and large brimmed hat could completely hide its wearer when their head was tilted slightly downward. Some mulattoes were able to pass as white guests.

Eliza Harris

One of the many slaves Coffin helped to escape was Eliza Harris, who had crossed the Ohio River on a winter night when it was frozen over, while barefoot and carrying her baby. She was exhausted and nearly dead when she reached Coffin home. The Coffins provided her with food, clothing, new shoes, shelter and rest before helping her continue on her journey to freedom.

Harriet Beecher Stowe was living in the city at the time and was well acquainted with the Coffins. Eliza’s story so moved Stowe that she retold it in her book Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852). Her kind Indiana Quakers named Simeon and Rachel Halliday were based on Levi and Catherine Coffin. The couple known for their secrecy became public figures.

The Civil War and Beyond

During the Civil War, the Coffins changed their focus to aiding freed people living in refugee camps. As Quakers they opposed to war, they did support the Union cause, and they spent almost every day at Cincinnati’s military hospital helping to care for the wounded.

After the war, the Coffins turned their attention to the Western Freedmen’s Aid Society, which helped educate and provide basic living needs for former slaves. Levi raised money in Europe and the American North to help African Americans establish business and farms after their emancipation. Toward the end of his life, Levi published his memoirs entitled Reminiscences of Levi Coffin, the Reputed President of the Underground Railroad (1876).

Levi Coffin died September 16, 1877 in Avondale, Ohio of a heart attack as he neared 80 years of age and was buried in historic Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati. Crowds of African Americans came to his Quaker funeral to say farewell.

Catherine Coffin died May 25, 1881 at the age of 78 from pneumonia. She was buried at the Friends burying ground in Cumminsville, but was later reinterred with Levi in the Quaker plot at Spring Grove.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Levi Coffin

Underground Railroad Depot

Indiana Historical Society: Levi and Catherine Coffin

Threads of Memory 3: New Garden Star for Catherine White Coffin

what color hair did cathrenie coffin have. srry spelled it wrong.