Saving Slaves from Bondage in the South

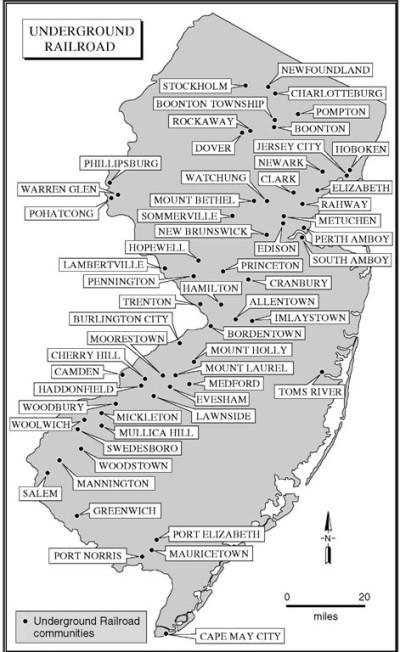

Tens of thousands of fugitives from the slave states of Maryland, Virginia, and North and South Carolina found refuge in New Jersey. Most of them arrived here by crossing the Delaware River under the cover of darkness. Slaves and the courageous people who aided them on their journey risked their lives for freedom. Quaker Abigail Goodwin was one of the figures whose work was instrumental in the success of the Underground Railroad in New Jersey.

Image: Stations on the NJ UGRR

Backstory

New Jersey’s path to abolition for all of its citizens was a rocky one. In 1804 New Jersey passed its first abolition law, An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery. It freed all black children born on or after July 4, 1804, after serving an apprenticeship to their mother’s owner for 21 years for females and 25 years for males. A law passed by the state legislature in 1826 stated that fugitive slaves from other states who were residing or apprehended in New Jersey had to be returned to their owners.

Runaways were mostly males between the ages of 15 and 30, who traveled at night to avoid bounty hunters and slave catchers, and to be able to see and follow the North Star. Families fled as well, but traveling with groups was more dangerous. They made their way North on foot, horseback, wagon, stagecoach, carriage, train, and/or boat.

Quakers and the UGRR

Quakers started the anti-slavery movement in the 1780s, but the Underground Railroad did not become legendary until the 1830s when abolitionists and their sympathizers began helping slaves who were passing through their towns. During the early 1800s, white, mostly Quaker, abolitionists who lived primarily in southern New Jersey began raising abolitionist sentiment by joining anti-slavery organizations. They also worked tirelessly to provide shelter, financial aid, and support to runaways.

Free Blacks and the UGRR

Free African Americans were invaluable conductors on the UGRR. They knew the safest locations as well as the dangers in the black world of southern New Jersey. These free blacks hid, fed, clothed, and cared for the passengers who reached their stations, which could be any kind of structure – a house, church, hotel, or store. They acted individually, in conjunction with the vigilance committees that were established in many northern cities, and through their churches.

The Mount Zion African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Church in the hamlet of Swedesboro, New Jersey was built in 1834. The members of Mount Zion always left the church doors unlocked in case escaping slaves were passing through and needed shelter. If they were being pursued by slavecatchers or their owners, the fugitives were secreted in a secure hiding place beneath the church’s vestibule.

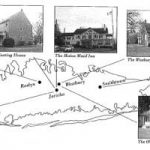

Image: Peter Mott House

Lawnside, Camden County, New Jersey

This house, built around 1844, is probably the only site in the U.S. that was owned and operated as a UGRR station by a black man in an all-black community. Peter Mott was a free black farmer, possibly a fugitive slave from Delaware, and he became a successful businessman who risked everything to assist fugitive slaves fleeing north.

New Jersey was also home to more all-black communities than any other northern state, and fugitive slaves sometimes decided to go no farther and settled in New Jersey, among people of like mind where they were comfortable. These tiny villages sprang up mainly in heavily wooded areas in rural settings in the southern part of the state. Several accounts exist of slave catchers being quickly dispersed when they were discovered in those areas.

New Jersey Underground Railroad

New Jersey was an integral part of the Underground Railroad in the Northeast, receiving fugitives from the Atlantic coastal slave states of Georgia, the Carolinas, Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware. It shared a border with the slave states of Delaware and Maryland, and it was located between Philadelphia and New York City, two of the most active UGRR cities in the country. In the summers between 1849 and 1852, Harriet Tubman, the most celebrated conductor on the UGRR, worked at a hotel in Cape May, New Jersey, earning enough money to return to her native state of Maryland to guide dozens of fugitives slaves to freedom.

William Still, a native of New Jersey, was distinguished as the most important UGRR operative in Philadelphia and the author of The Underground Railroad. In this book, Still recounts the stories of the fugitives he aided in Philadelphia, and it is especially noteworthy because it makes the fugitives – not the abolitionists who assisted them – the true heroes of the Underground Railroad.

In 1831 William Lloyd Garrison printed the first issue of The Liberator, an antislavery newspaper. Slavery was abolished in the British Empire in 1833, making Canada a safe place for runaway slaves to settle.

Black and white activists – called radical abolitionists – were impatient with the gradual emancipation preferred by anti-slavery reformers. They wanted an immediate end to slavery. With the founding of the American Anti-Slavery Society and the formation of vigilance committees in major northern cities, helping slaves move along until they reached a place where they could be free was the next logical step in the process. It would forever be known as the Underground Railroad.

The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 gave the federal government primary responsibility for capturing slaves fleeing to the North, causing free blacks to fear they would be kidnapped and returned to bondage and influencing fugitive slaves to flee to Canada. All was much the same until the Civil War began in 1861, hundreds of thousands of slaves deserted their masters and fled to Union invaders, relying on the Union Army to care for them and keep them free.

Image: Edgewater Mansion at Croft Farm

Cherry Hill, Camden County, New Jersey

This sixteen-room farmhouse, constructed in 1741, served in the antebellum period as a UGRR station. It was purchased in 1816 by Thomas Evans, a Quaker abolitionist. By 1840, Thomas Evans had moved to Haddonfield and left the house to his son, Josiah Bispham Evans, who continued to use it as a safe house. A 1918 handwritten statement by Walter Evans, a descendant of Thomas and Josiah Evans, traces the history of the house, and his family’s oral tradition documents it as a UGRR stop:

[It] was one of the stations to which runaway slaves were brought. The slaves came from Woodbury and were received by Thomas Evans, then quickly hidden in the attic of the house so that no one could find them. Then, in the middle of the night, they would be given something to eat and hurried off in a covered wagon to Mount Holly, where they were received and hidden again.

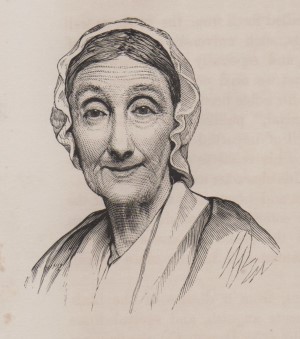

Abigail Goodwin

A number of Underground Railroad sites in southern New Jersey remain, particularly in Salem County, where Quaker residents were actively involved. The town of Salem offered an escape route for self-emancipating slaves fleeing from Delaware, Maryland and points South. These fugitives could find a sanctuary at the home of Quaker Abigail Goodwin and her sister Elizabeth, who operated a major Underground Railroad station in Salem. The father of these compassionate women had set an excellent example for his daughters by freeing all of his slaves during the American Revolution, as had most members of the local Society of Friends. Abigail was ejected from the Orthodox Quaker Meeting in Salem for joining a group of radical Quakers fighting for the total abolition of slavery.

During the 1830s, Abigail Goodwin became involved with black abolitionist William Still, chairman of the Vigilance Committee in Philadelphia, some forty miles away. She emerged as an activist for the abolitionist and Underground Railroad movements, working with abolitionists in Salem. By 1838 the Goodwin home at 47 Market Street in Salem was a station on the UGRR, a center for abolitionists and a beacon for freedom seekers. There, she provided nourishment, fresh clothes and a place to rest their weary bones, without the constant fear of being captured and returned to bondage, until they gathered the strength to continue on their journey North.

The Goodwin home also became a center for abolitionists. The sisters came into contact with leading anti-slavery figures, including Lucretia Mott and James Miller McKim, who came to Salem to lecture as their guest. His speech, however, attracted a mob of anti-abolitionists who pelted the Goodwin house with sticks and rocks. The attack deepened the sisters’ commitment. They led efforts to collect food, clothing, and financial donations to assist those escaping slavery along the Salem Line. Although of modest means themselves, the Goodwins generously sacrificed in order to assure the freedom and safety of others.

Due in part to the efforts of the Goodwin sisters, many slaves living in Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia knew that this region was a safe place for runaways. Abigail Goodwin urged her Quaker friends to donate food, clothing, and money for the runaway slaves. A fellow abolitionist wrote, “Abby denied herself even the necessary apparel and few beggars came to our doors whose garments were so worn, forlorn, and patched-up as Abby’s.” Goodwin also made clothing for runways and wrote to a friend:

I should like to know if the fugitives are mostly large. … I want to know in regard to the clothes that I intend making. … They ought to be fitted out for Canada with strong, warm clothing in cold weather, and their sad fate alleviated as much as can be.

In addition to providing lodging, food, clothing and other necessities to fugitive slaves, Goodwin raised money, some of which she used to buy a group of slaves in North and South Carolina, and then set them free. This practice was not sanctioned by the abolitionist organizations to which she belonged. Goodwin wrote:

I don’t like buying them, or giving money to the slave-holders either; but this seems to be a peculiar case, can be had so cheap, and so many young ones that would be separated from their parents.

Abigail Goodwin’s UGRR work, from the 1840s until the Civil War, has been documented by her own correspondence with William Still and other abolitionists, as well as a diary kept by a nephew. It has been said that slave hunters occasionally approached her in disguise but never fooled her. She often sent warnings to other UGRR stations about authorities lurking nearby disguised as salespeople or travelers.

In this letter dated August 1, 1855, Goodwin writes to William Still offering to organize a “committee of women” who would focus on the needs of female fugitives. She also asks if he planned to celebrate August 1, Emancipation Day – the day that slavery was abolished in Great Britain:

Would it not be well to get up a committee of women, to provide clothes for fugitive females- a dozen women sewing a day, or even half a day of each week, might keep a supply always ready, they might, I should think, get the merchants or some of them, to give cheap materials – mention it to thy wife, and see if she cannot get up a society. I will do what I can here for it. I enclose five dollars for the use of fugitives. It was a good while that I heard nothing of your railroad concerns; I expected thee had gone to Canada, or has the journey not been made, or is it yet to be accomplished, or given up? I was in hopes thee would go and see with thy own eyes, how things go on in that region of fugitives, and if it’s a goodly land to live in.

This is the first of August, and I suppose you are celebrating it in Philadelphia, or some of you are, though I believe you are not quite as zealous as the Bostonians are in doing it. When will our first of August come? oh, that it might be soon, very soon! It’s high time the reign of oppression was over.

Only Abigail Goodwin lived to see slavery abolished in 1865; she passed in 1867. In 1872, William Still published his book The Underground Railroad. In a section devoted to Abigail, he wrote:

Abigail Goodwin, of Salem, N.J. was one of the rare, true friends to the Underground Rail Road, whose labors entitle her name to be mentioned in terms of very high praise.

Walk Across New Jersey

The Harriet Tubman and William Still Underground Railroad Walk Across New Jersey: Celebrating New Jersey’s History and Heroes Every Step of the Way took place September 29 through October 13, 2002. This celebration highlighted a unique part of the state’s history and the freedom network that operated from Cumberland to Hudson County. Members of the New Jersey Department of State traversed the 180-mile path the Underground Railroad took through New Jersey.

Image: Quaker Abigail Goodwin

Stationmaster on the New Jersey UGRR

Abigail Goodwin House

In 2008, the Abigail Goodwin House at 47 Market Street in Salem was designated as the first site in New Jersey accepted into the National Park Service’s National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom. It is also a site on the New Jersey Women’s Heritage Trail.

SOURCES

The Underground Railroad in New Jersey – PDF

State of New Jersey: The Underground Railroad

New Jersey’s Underground Railroad Heritage – PDF

Mt. Zion A.M.E. Church: The Underground Railroad

Croft Farm National Recreation Trail, Cherry Hill, NJ