Wife of American Traitor General Benedict Arnold

By Sir Thomas Lawrence

Peggy (Margaret) Shippen was born on July 11, 1760, to one of the most prominent families in Philadelphia, which included two Philadelphia mayors and the founder of Shippensburg, Pennsylvania. Her mother Margaret was the daughter of prominent lawyer Tench Francis and her father Edward Shippen IV was a judge, who tried to remain neutral during the American Revolution, but the family was well-known for their loyalist tendencies, meaning loyal to the British. With the creation of the state of Pennsylvania in 1776, Shippen lost his judgeship and other political offices he had held under the royal government.

Peggy was the youngest child of the family, though there were two other boys born later who died in infancy, and soon became her father’s favorite. As a girl, Peggy enjoyed music, drawing and needlework; however, her main interests were in newspapers and political jargon. She had a loving admiration of her father and from him she learned about politics and the Revolution.

In 1777, when the British occupied Philadelphia, the Shippen family moved to a farmhouse northeast of the city. Judge Shippen thought they would be safer in their city home, since the surrounding area had been the scene of numerous battles and skirmishes, so the family returned to the city.

The Shippen family held many social gatherings at their home. A favorite among British officers during the British occupation of Philadelphia, Peggy met and had at least a flirtation with Major John Andre, an officer in General William Howe’s command. He became a regular visitor to the Shippen household and favored Peggy among the girls. In June 1778, the British withdrew from the city, but Peggy stayed in contact with Andre.

Soon after, Peggy Shippen became acquainted with widower and Revolutionary War General Benedict Arnold, the hero of the Battle of Saratoga and the new military governor of Philadelphia. In spite of the differences in their political views, the two began a courtship, and Arnold soon sent Peggy’s father a letter asking for her hand. Edward Shippen was skeptical of Arnold, but eventually consented to the engagement.

On April 8, 1779, 37-year-old Arnold married 18-year-old Peggy. Arnold purchased Mount Pleasant manor on the Schuylkill River for his bride, and specifically made the property over to her ownership and that of their future children. They occupied the property as their country estate in 1779 and 1780.

The couple returned to Philadelphia, residing in the city’s military headquarters. Arnold’s quarters were in the occupied home of Richard Renn at Fifth and Market Streets, which had also been the military headquarters of General Howe prior to the British withdrawal.

After the British withdrew from Philadelphia in June 1778, General George Washington appointed Arnold military commander of the city. Even before the Americans reoccupied Philadelphia, Arnold began planning to capitalize financially on the change in power there, engaging in a variety of business deals designed to profit from war-related supply movements and benefiting from the protection of his authority.

Court Martial

In 1779, the Council of Pennsylvania filed charges of corruption and mishandling of government money against Arnold that occurred during his previous military campaigns. Arnold demanded a court martial to clear his name.

The court martial to consider the charges against Arnold began meeting on June 1, 1779, but was delayed until December 1779. In spite of the fact that a number of members of the panel of judges were ill-disposed to Arnold over actions and disputes earlier in the war, Arnold was cleared of all but two minor charges on January 26, 1780. Arnold worked over the next few months to publicize this fact; however, Washington published a formal rebuke of Arnold’s behavior.

Shortly thereafter, a Congressional inquiry into his expenditures concluded that Arnold had failed to fully account for his expenses incurred during the Quebec invasion, and that he owed the Congress some £1000, largely because he was unable to document them. A significant number of these documents were lost during the retreat from Quebec. Angry, frustrated and deeply in debt, Arnold resigned his military command of Philadelphia in late April 1780.

Espionage and Defection

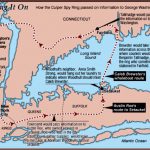

During this time, Peggy Arnold was also keeping in contact with Major John Andre, who had been made British General Henry Clinton’s spy chief. The Arnolds also had many close friends who were either actively Loyalist or sympathetic to that cause. In May 1779, Benedict Arnold initiated communications offering his services to the British. General Henry Clinton ordered Major Andre to pursue the possibility, and secret correspondence between Arnold and Andre began.

Letters were passed through the women’s circle that Peggy Arnold was a part of, and she knew that some letters contained instructions written in both code and invisible ink that were to be passed on to Andre. By July 1779, Arnold was providing the British with information about troop locations and strengths, as well as the locations of supply depots, all the while negotiating over compensation.

Furthermore, Patriot mobs were scouring Philadelphia for Loyalists, and Arnold and the Shippen family were being threatened. Arnold was rebuffed by Congress and by local authorities when he requested security details for himself and Peggy’s family.

During July and August 1780 there was a flurry of communications between Benedict Arnold and General Clinton about West Point – the most critical American defense post in the Hudson River highlands – which Clinton was interested in capturing. Meanwhile, Arnold’s letters continued to detail Washington’s troop movements and provide information about French reinforcements that were being organized.

On August 3, 1780, through some maneuvering, Arnold obtained command of West Point. Peggy joined him there, and it was there that their first child was born. In mid-August Arnold basically offered to give West Point to the British for £20,000. On August 25, General Clinton accepted.(In his defense, supporting Peggy’s lifestyle must have been very difficult for Arnold.)

Arnold systematically began to weaken the defenses and military strength at West Point making it easier for the British to capture. Troops were liberally distributed within Arnold’s command area, leaving only a few at the fort itself. He also drained West Point’s supplies; his subordinates eventually concluded that Arnold was selling some of the supplies on the black market for personal gain.

In September 1780 Arnold forwarded documents to Major John Andre that revealed the fortifications at West Point, just as the British were preparing to capture the fort. However, Andre was arrested on September 23, carrying information concerning the planned surrender of the fort and the plot was exposed. Arnold was alerted to Andre’s capture, and that the papers found in his possession were on their way to General George Washington, with whom Arnold was supposed to meet that morning.

After a military trial, Major John Andre was condemned to death as a spy and was hanged on October 2, 1780, at Tappan, New York. At his execution, he asked the audience to remember that he died bravely, and his plight and courage moved many on both sides of the war, and left Arnold even more despised by the British. Clinton, who already disliked Arnold, blamed him for the death of his favorite aide.

General Washington infiltrated men into New York City in an attempt to kidnap Arnold; this plan, which very nearly succeeded, failed when Arnold changed living quarters. Arnold attempted to justify his actions in an open letter titled To the Inhabitants of America, published in newspapers in October 1780.

Fearful for her own safety, Peggy had returned to Philadelphia to stay with her family, but she was banned from the city on October 20, 1780, and joined Arnold in New York City. Their second child, James Robertson Arnold, was born in New York on August 28, 1781.

Arnold’s defection to the British worked out well for him. He received substantial compensation, including pay, land in Canada, pensions for himself, his wife and his children (five surviving from Peggy and three from his first marriage) and a military commission as a British Provincial brigadier general.

With hostilities in North America apparently winding down after Cornwallis’ surrender at Yorktown in October 1781, the Arnolds sailed for London on December 15, 1781, arriving January 22, 1782. Peggy was initially welcomed warmly in England, as was her husband. She set up a home in London while Arnold built a trading business. A daughter and a son died in infancy in 1784 while the Arnolds lived in London.

In 1784, Arnold left for a business opportunity in Saint John, New Brunswick. During Arnold’s stay there, Peggy gave birth to their Sophia Matilda, and Arnold fathered an illegitimate child (John Sage). Peggy sailed to Saint John to join Arnold in 1787, leaving her two older sons with a private family in London; in New Brunswick, Peggy gave birth to son George in 1787.

In 1789 Peggy returned briefly to the United States, accompanied by her daughter Sophia and a maid, to visit her family; she was treated coldly by Philadelphians. She returned to New Brunswick in the spring of 1790. Arnold’s difficulties with local businessmen prompted their return to London in January 1792. As they were leaving, angry mobs were gathering on their property, calling them ‘traitors.’ Their last child, William Fitch, was born in London in 1794.

In January 1801 Arnold’s health began to decline. He suffered from gout, and near the end he walked only with the aid of a cane.

On June 14, 1801, Benedict Arnold died at the age of 60, being infamously remembered as a traitor and a spy. His death left Peggy to deal with a bad name and many debts.

Peggy Shippen Arnold died of cancer on August 24, 1804, in England.

Peggy’s Role in the Conspiracy

In the 19th century, after all of the principals had died, Aaron Burr biographer James Parton published an account implying that Peggy Shippen Arnold had manipulated or convinced Benedict to change sides. The basis for this claim was interviews he conducted with Theodosia Prevost, who later married Aaron Burr, and notes later made by Burr.

While en route to Philadelphia from West Point in 1780, Peggy visited with Prevost at Paramus, New Jersey. According to Parton, Peggy unburdened herself to Prevost, claiming she “was heartily tired of all the theatricals she was exhibiting”, referring to her histrionics at West Point. According to Burr’s notes, Peggy “was disgusted with the American cause” and

“that through unceasing perseverance, she had ultimately brought the general into an arrangement to surrender West Point.”

When these allegations were first published, the Shippen family countered with allegations of improper behavior on Burr’s part. They claimed that Burr rode with Peggy in a carriage to Philadelphia after her stay with Mrs. Prevost, and that he fabricated the allegation because she refused advances he made during the ride.

Arnold biographer Willard Sterne Randall opines that Burr’s version has a more authentic ring to it: first, Burr waited until all were dead before it could be published, and second, Burr was not in the carriage on the ride to Philadelphia. Randall also notes that ample further evidence has since come to light showing that Peggy played an active role in the conspiracy. British papers revealed in 1792 that she was paid £350 for handling some secret dispatches.

SOURCES

Benedict Arnold

Wikipedia: Peggy Shippen

Wikipedia: Benedict Arnold