Wife of Revolutionary War General Benjamin Lincoln

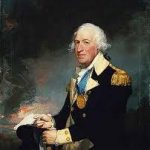

Major General Benjamin Lincoln

Charles Willson Peale, Artist

Mary Cushing was born in 1730, the daughter of Elijah Cushing and Elizabeth Barker Cushing of Pembroke, Massachusetts, whose ancestors were among the founders of Hingham, Massachusetts. Benjamin Lincoln was born on January 24, 1733, the son of Colonel Benjamin Lincoln (1699-1771) and Elizabeth Thaxter Norton Lincoln also of Hingham, MA. He spent his early life working on the family farm, and attended the local school.

A prominent farmer, Benjamin’s father was a Colonel and served on the Governor’s Council as well as in the Massachusetts House of Representatives. His father’s wealth allowed him to accept responsibilities at an earlier age than most of his contemporaries. At 21 in 1754, he became town constable, a combination policeman and tax-collector.

Lincoln gained his first military experience in the French and Indian War, which began in 1754 and ended in 1763. As an established farmer and family man, he did not volunteer to take part in the fighting, but was involved in recruitment, training, and supplying his father’s regiment, the Third Suffolk. By the end of the war, Lincoln had reached the rank of Major.

On January 15, 1756, Benjamin Lincoln married Mary Cushing. They had eleven children.

Political Career

In 1757, Lincoln was elected town clerk of Hingham, an office which both his father and grandfather had held before him, and which Lincoln would hold for twenty years. This post helped make him one of the town’s leaders by the age of twenty-five. In 1762, he was appointed Justice of the Peace.

Immediately after the French and Indian War, the protests against Great Britain that would eventually lead to revolution began. Lincoln’s father was still on the Governor’s Council, where he was a political moderate and disliked the new radical atmosphere, but his position on the Council became increasingly difficult as Massachusetts polarized.

Hingham’s politics were in step with the increasingly revolutionary tone of the state, but remained more moderate than the radical Bostonians. Lincoln remained in the background while his father was still active, but after his father retired from the Council in 1769, Lincoln was free to follow his own more radical inclinations.

In 1770, in a list of resolutions passed by the inhabitants of Hingham, Benjamin Lincoln outlined the measures urged by Hingham residents towards the non-importation of British goods and condemned the Boston Massacre, during which several Patriots were killed.

Lincoln’s father died in 1771, leaving Benjamin the head of the family and increasing his prominence in Hingham. The following year, he was elected to the Massachusetts General Court. Lincoln, like many others, believed that the British wanted to suppress American liberty.

Lincoln rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel in the Suffolk Militia in 1772, which allowed him to gain military experience that he would use in three major battles of the Revolutionary War. As the Revolution approached, he took a stronger Whig position than most of the other leading inhabitants of Hingham, and he came to a wider prominence towards the end of 1774.

The new royal governor, British General Thomas Gage, ordered the election of a new General Court. Lincoln was elected to the court in September 1774. However, Gage quickly dissolved it when it became clear that its members were not going to cooperate with him.

Rather than return home, the members of the General Court declared themselves a Provincial Congress, which met three times over the next nine months, at Concord, Cambridge, and Watertown, Massachusetts. Lincoln was appointed secretary of the Congress, and he worked to replace officials appointed by the Royal governor and council with reliable Whigs (Patriots). The Congress dedicated itself to gathering military supplies and finding safe places to store the arms.

Lincoln was not directly involved in the fighting at Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775. In the immediate aftermath, the local militia regiments rushed towards Boston. The Provincial Congress also reacted quickly, re-convening on April 22. Once again, Lincoln was appointed to a key post as muster master of militia, and as a member of the Committees of Safety, Supply, and Governmental Organization.

In July 1775, the Provincial Congress was replaced by a newly-elected House of Representatives. Lincoln was elected to this House, and on July 28 was appointed to the twenty-eight member executive council. Lincoln met General George Washington in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in July 1775.

During the second half of 1775, Lincoln’s roles remained largely organizational and political. He played a part in supplying gunpowder and blankets to the army besieging Boston, as well as helping to fit out ten privateers (privately owned warships).

In February 1776, Benjamin Lincoln was promoted to Brigadier General of the militia, to Major General in May, then commander of all Massachusetts troops in the Boston area. He resigned his last posts in Hingham, and moved entirely onto the state stage.

Military Career in the North

On March 17, 1776 the British evacuated Boston, and retreated to Halifax, Nova Scotia, but they still maintained a naval presence in the outer harbor. Lincoln put together a plan to force the British out of their anchorages, and was given permission to use the militia to put his plan into action.

On the night of June 13, cooperating with General Artemas Ward, commander of the Continental forces in Massachusetts, General Lincoln and a force of militia erected gun batteries on Long Island, Peddocks Island, and Nantasket Head in the outer Boston harbor. The following day, the British ships still remaining in Boston harbor were forced to sail away.

In September 1776, after the American defeat on Long Island, New York, Massachusetts sent 5000 militiamen on temporary assignment to New York, and Lincoln was selected its commander. He reached his new command, at their muster point in Connecticut, on September 28, expecting to march them with all possible speed to join with Washington.

Finally, in mid-October, with the American armies around New York in disarray, Washington called for Lincoln’s troops, and they arrived in time for the White Plains Campaign. His division formed part of the rear-guard as Washington withdrew into a new defensive position, before withdrawing to join the main American line. On October 28, 1776, the British attacked this line at the Battle of White Plains, forcing the Americans into another retreat.

In mid-November 1776, General Lincoln’s men were due to be discharged – their temporary assignment was over. Despite the best efforts of Washington and Lincoln to persuade them to stay, the Massachusetts division marched home. Lincoln returned with them, some of his faith in the militia system destroyed.

Lincoln commanded forces during General William Heath’s manuevers against Fort Independence, New York, on January 17-25, 1777. Heath broke his forces into three groups, one of which was commanded by Lincoln, to overtake the British positions. When he reached the fort, his order for surrender was instead met by artillery. After several days, the British scattered Heath’s forces. This, along with news of a coming blizzard, convinced Heath to withdraw. The disgrace that fell to Heath after this failure did not spill over onto Lincoln.

On February 19, 1777, the Continental Congress followed General Washington’s recommendation, and commissioned Lincoln into the Continental Army as the 16th Major General. Shortly thereafter, Lincoln joined General Washington in Winter Quarters at Morristown, Pennsylvania, with a new levy of militia.

Lincoln’s first command as a Continental officer came at the end of February, when he was appointed to command a force of over 1000 men at Bound Brook, New Jersey, guarding a pass through the Wachtung Mountains, only three miles from the British lines. Despite increasing British activity, the Massachusetts militia once again left him, one week after their period of enlistment ended on March 15, leaving him with only 500 men.

On Sunday April 13, 1777, four thousand British troops commanded by General Charles Cornwallis launched a raid on Bound Brook. Lincoln managed to organize a rapid retreat under fire, but he still suffered 60 casualties, as well as the loss of three artillery pieces. The British force withdrew on the same day, and Lincoln spent the night back in his original quarters, but the message of American vulnerability was clear. While his colleagues felt Lincoln was clear of any blame, he seems to have been less happy with his conduct and determined to make good his reputation.

Lincoln remained attached to Washington’s command until July 1777, when he was sent with General Benedict Arnold to act under General Philip Schuyler against British General John Burgoyne, and he raised a body of New England militia to take with him. He sent out a successful expedition, which seized the enemy posts at Lake George, and broke Burgoyne’s line of communication.

On July 23, 1777, the main British army sailed from New York on the way to conquer Philadelphia. Washington immediately acted to reinforce the campaign against Burgoyne’s invasion from Canada. Among the moves he made was the appointment of Lincoln to command the New England militia, upon whom the entire campaign might hinge.

Command of the campaign was held by Northern Department Commander, General Philip Schuyler, who had slowly retreated before the British advance, a policy that was slowly weakening Burgoyne’s army. However, after his surrender of Ticonderoga, Schuyler’s actions became increasing unpopular in New England.

By the time Lincoln arrived, the New England militia were no longer obeying Schuyler’s orders. Desertion was rife, while new militia forces failed to arrive. Washington’s hope was that Lincoln’s reputation as an ex-militia commander was sufficient to restore the morale of the New England militia.

Lincoln joined his new command on August 2 at Manchester, Vermont. His orders from Schuyler were to move north towards Skenesborough if it could be done “without risking too much.” On his arrival, Lincoln found only five hundred men, although 2000 more were expected. While he was waiting for their arrival, the British reached the Hudson River, eight miles south of Skenesborough. Schuyler changed his plans, ordering Lincoln to bring the militia to his aid.

This order caused Lincoln two problems. First, he was convinced that the correct use for his militiamen was to harass the British rear, now very vulnerable. Second, his reinforcements – the New Hampshire militia commanded by General John Stark – had arrived on August 7, but Stark made it clear that he would not serve with the Continental Army, because he had been passed over for promotion.

Instead of alienating Stark, Lincoln worked to modify Continental strategy to fit around Stark’s objectives. Lincoln rode to Stillwater, where he was able to persuade Schuyler to revert to their original plan. On August 16, Stark’s men defeated a British force at Bennington, substantially weakening Burgoyne’s force and denying them vital supplies.

By the time Lincoln met with Schuyler, Schuyler knew that he had been replaced by General Horatio Gates, who had long campaigned for the northern command. On August 18, 1777, Gates reached the army, and on August 20, Lincoln once again put forward his plan to strike at the British rear. Gates agreed to the plan, but Lincoln was now frustrated by the slow arrival of the militia.

Lincoln was not ready to move until September 12. On the following day, Burgoyne crossed the Hudson, cutting himself off from his own supply lines and making Lincoln’s expedition largely irrelevant. Even so, his forces gained a series of successes against the isolated British bases left behind by Burgoyne. Despite these victories, the main battle was being fought by Gates – the First Battle of Saratoga, on September 19, which frustrated a British attempt to break through the American lines.

General Lincoln then joined General Horatio Gates at Stillwater, New York, arriving on September 22, and took command of the right wing. All of his troops arrived by September 29. During the Battle of Bemis Heights on October 7, 1777, Lincoln commanded inside the American works. The next day, while leading a small force to a post in the rear of Burgoyne’s army, Lincoln encountered a party of British, and he was shot – a musket ball shattered his right ankle.

Lincoln was able to escape back to the American lines, and he was evacuated to Albany. At first it looked like he might lose his leg, but by October 19, he had recovered enough to be sure that he would recover fully. Despite missing the final British surrender, Lincoln’s role in the campaign was fully appreciated.

Lincoln was unable to travel for several months, and finally arrived at Boston on February 23, 1778. He spent the next five months at Hingham recuperating from his wound. His leg slowly healed, although it was to be years before it fully recovered. In the end, his left leg was two inches shorter than his right, and would bother him for the rest of his life.

General Lincoln rejoined the main army outside White Plains on August 6, 1778. His main occupation after his return to the army was to preside over the courts-martial of St. Clair and Schuyler. Both men were acquitted, but neither gained another senior command. The decisions they had made were generally accepted in military circles to have been correct, but the political uproar had forced their trials.

Military Career in the South

When General Lincoln returned to duty in August 1778, he rejoined General Washington’s main army. On September 25, 1778, he was appointed by Congress to replace General Robert Howe as commander of the Southern Department. Having been delayed in Philadelphia by Congress, he did not arrive in Charleston, South Carolina, until December 4, 1778. The timing of his arrival made him unable to prevent the capture of Savannah, Georgia, on December 29th.

Soon after his arrival, Lincoln shored up a position south of Charleston to protect it from being captured by General Augustine Prevost, a Swiss mercenary serving in the British Army. Meanwhile, Lt. Colonel Archibald Campbell marched virtually unopposed against Augusta, Georgia, occupying it on January 29, 1779. An advance force sent by Prevost was rebuffed by General William Moultrie at Beaufort, South Carolina, on February 2, 1779.

General Moultrie’s victory helped bolster Lincoln’s ranks with additional militia, so he undertook a counteroffensive to regain Georgia. The British evacuated Augusta, Georgia, while General Andrew Pickens was victorious at Kettle Creek, Georgia, on February 14, 1779. However, the counteroffensive stalled when a 1500 man force under General John Ashe was destroyed at Briar Creek, Georgia on March 3. This was followed by an advance by General Prevost against Charleston, and Lincoln was forced to retreat back to Charleston to protect the city.

In May 1779, British troops commanded by General Augustine Prevost moved into Charleston and began negotiating for the city’s surrender, but Lincoln was able to trap Prevost on St. James Island. Frustrated by the lack of support from other commanders and from South Carolina President Rawlins Lowndes, Lincoln tendered his resignation, but the South Carolina Council convinced him to stay.

The oppressive heat of the summer months halted major operations on both sides for several months. Lincoln spent this time appealing to French Admiral Count d’Estaing to sail from the West Indies and join in the efforts to recapture Georgia. In September 1779, d’Estaing arrived to the complete surprise of the British.

The Siege of Savannah consisted of a joint Franco-American attempt to retake Savannah from the British in September and October 1779. On October 9, 1779, General Lincoln joined d’Estaing in a major assault against the British siege works, but they failed to retake the city. Although Lincoln pleaded to continue the siege, the French abandoned the offensive on October 20. The British remained in control of coastal Georgia until they evacuated it in July 1782, close to the end of the war.

In February 1780, British General Sir Henry Clinton arrived in South Carolina, leading a large expedition from the northern colonies with the purpose of subjugating the Southern colonies. In March 1780, the city was surrounded by a sizable British force. Lincoln relied on Commodore Abraham Whipple’s expertise to protect Charleston Harbor, but Whipple gave up the harbor without a fight. The British easily secured use of the waterways around Charleston.

In April, Clinton’s forces trapped Lincoln and his troops in the Siege of Charleston. Lincoln was left with little to do, but watch as the British slowly closed in. Faced with dwindling food supplies, pressure from Charleston citizens, and failed attempts to negotiate a truce with the British, Lincoln was forced to surrender the city to Clinton on May 12, 1780.

Lincoln, desperate for more troops, had pleaded with the South Carolina legislature to arm 1000 enslaved African Americans to ward off the approaching British. Rather than see armed slaves, the legislature began negotiations with the British commanders to allow the British forces to pass through South Carolina. The British subsequently sought to enlist large numbers of black soldiers.

Denied the courtesy of the customary honors of war allowed a defeated enemy, Lincoln’s army was forced to march out of Charlestown without flags flying, weapons shouldered or playing a British march. (Honors of war included the privilege of playing a tune favored by the enemy as a gesture of defiance by the defeated force.)

General Benjamin Lincoln was paroled following his surrender of Charleston on May 12, but he did not reach Philadelphia until July 1780. He requested a court of inquiry to investigate his conduct at Charleston, but none was appointed and no charges were ever brought against him. He returned to his farm at Hingham and waited to be exchanged.

Finally in November, 1780, he was exchanged and spent the winter recruiting and gathering supplies in Massachusetts. At the Harvard commencement a month later, when Benjamin Lincoln, Jr., received his Masters degree, Lincoln was awarded an honorary degree.

In June 1781, General Lincoln joined General Washington’s main army on the North River (the colonial name for the southernmost portion of the Hudson River). That summer, he commanded troops around New York City.

Siege of Yorktown

The northern, southern, and naval theaters of the war converged in 1781 at Yorktown, Virginia. In early September, French naval forces defeated a British fleet at the Battle of the Chesapeake, cutting off Cornwallis’ supplies and transport. In August 1781, Washington hurriedly moved his troops from New York, selecting Lincoln to lead the American army in its march south to Yorktown, Virginia. He served as Washington’s second-in-command at the Siege of Yorktown.

A combined Franco-American force of 17,000 men began the siege of Yorktown in early October 1781. Cornwallis’ position quickly became untenable, and he surrendered his army on October 19.

Surrender of Cornwallis

John Turnbull, Artist

The surrender of British forces at Yorktown, Virginia, assured the defeat of the British forces in America. George Washington and the Marquis De Lafayette watch as Major General Benjamin Lincoln (on horseback) accepts the surrender on October 17, 1781.

Pleading illness, General Charles Cornwallis did not attend the surrender ceremony, choosing instead to send his second-in-command, the Irish General Charles O’Hara. In response, General Washington refused to accept O’Hara’s sword. General Lincoln received the British surrender. Lincoln left active field duty after Yorktown.

The surrender at Yorktown was not the end of the war: the British still had 30,000 troops in North America, and still occupied New York, Charleston, and Savannah. Both sides continued to plan upcoming operations, and fighting continued on the western front, in the south, and at sea.

In London, however, political support for the war plummeted after Yorktown, causing Prime Minister Lord North to resign soon afterwards. In April 1782, the British House of Commons voted to end the war in America. Preliminary peace articles were signed in Paris in November 1782, though the formal end of the war did not occur until the Treaty of Paris was signed on September 3, 1783 and the United States Congress ratified the treaty on January 14, 1784. The last British troops left New York City on November 25, 1783.

After the Revolutionary War

On October 30, 1781, Benjamin Lincoln was appointed the first Secretary of War. His struggle to maintain the army as the war wound down placed him at the center of the demobilization crisis. Congress did not have the funds to pay enlisted men and officers who had served in the war. Lincoln met with General Washington to go over Congress’ plan to demobilize the army. The centerpiece of the strategy was to grant enlisted men indefinite furloughs rather than immediate discharges, accompanied by three months pay of what were in many cases years of delayed payment.

The ties forged among Benjamin Lincoln and other officers of the Continental Army, through years of shared struggles and hardships as well as victories, were strong. The knowledge that they were parting, perhaps forever, made the end of the war bittersweet. Lincoln and dozens of fellow officers met at Fraunces Tavern in New York City on December 4, 1783. With tears in his eyes, General Washington shook hands with each man, and one observer recalled: “I do not think there were ever so many broken hearts in New York as there were that night.”

Lincoln served as Secretary of War until the signing of the Treaty of Paris on September 3, 1783, after which he retired to his farm, receiving the thanks of Congress for his services. In 1784, Lincoln got involved with land speculating in Maine and was chosen as the agent to negotiate a treaty with the Penobscot Indians.

Shays’ Rebellion

Daniel Shays was a poor Massachusetts farmer who had fought during the war, and was eventually wounded in action. In 1780, he resigned from the army unpaid and went home to find himself in court for the nonpayment of debts. He soon found that he was not alone. Shays led an armed uprising in central and Western Massachusetts; most of his compatriots were poor farmers angered by crushing debt and taxes.

Failure to repay such debts often resulted in imprisonment in debtors’ prisons or confiscation of property by the government. They attempted to prevent the courts from seizing property from indebted farmers by forcing the closure of courts in western Massachusetts. On January 1, 1787, Lincoln was put in command of the Massachusetts militia marching against the insurgents, and he personally raised $20,000 to finance the expedition.

Barred from using military force unless the rebels fired first, Lincoln sent mobile parties in every direction, apprehending and disarming the insurgents. At the same time, he spread the word that he would intercede with the government on behalf of rebels who peaceably surrendered, and many of them did.

On the night of February 3, 1787, he led a surprise attack on the Shaysite headquarters at Petersham, Massachusetts, scattering the main rebel forces and forcing Daniel Shays to flee. Shays escaped to Vermont and was later pardoned. Others were not so fortunate – 150 were captured and several were sentenced to death. George Washington and others urged compassionate treatment of the rebels and pardons were eventually granted.

Lincoln remained active in public life in various capacities. In 1787, he was elected Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts, but was defeated in the next election by Samuel Adams. In January 1788, Hingham sent Lincoln to the Massachusetts convention, where he used his influence to ensure ratification of the federal Constitution.

In February 1789, Washington appointed Lincoln the first Collector of the Port of Boston. Lincoln took a mansion on State Street and turned it into a combined residence and customs house.

In the summer of 1789, Lincoln was appointed Commissioner Plenipotentiary to negotiate a peace with the Creek Indians in Georgia, whose military power exceeded that of the infant federal government. Negotiations failed, however, and on his return to New York, Lincoln drew up a plan of campaign against the Creek. In April 1793, he joined another peace delegation to negotiate with northern Indians at Sandusky, Ohio, but these talks were also unsuccessful.

In 1790, Hingham elected Lincoln to the House of Representatives. He also operated a flour mill on the Weir River, joined the Third Church of Hingham, and served as a trustee of Derby Academy.

Lincoln was active in many organizations throughout his life, including the Philadelphia Agricultural Society, the Society for Propagating the Gospel among the Indians and Others in North America, the Massachusetts Humane Society, and the Society for Information to Foreigners. He was secretary of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and president of the Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati.

Mary Cushing Lincoln died in 1796.

Lincoln still remained active. He helped to found Boston Magazine and contributed many articles to contemporary publications on subjects as wide-ranging as reforestation, fish migration, and the need for settlement in Maine. Lincoln became a member of the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1798.

On March 1, 1809, he resigned from his post as collector and retired to Hingham.

General Benjamin Lincoln died at his home in Hingham, Massachusetts on May 9, 1810. The bells at Boston and other places were tolled for an hour; the flags of vessels, and those at Fort Independence and Fort Warren were lowered to half-mast.

General Lincoln was buried in the Old Ship Burying Ground behind Old Ship Church in Hingham. Among the pallbearers at Lincoln’s funeral were John Adams, Cotton Tufts, Robert Treat Paine, Richard Cranch, and Thomas Melville.

General Benjamin Lincoln was one of the few men to have been present at the three major surrenders of the Revolutionary War: twice as a victor (at Yorktown and Saratoga), and once as the defeated party (at Charleston). In spite of the major role he played during the war, he tends to be less well-remembered than many of his contemparies in the Continental Army.

Lincoln was a prosperous farmer who left the comfort of his Hingham home to join in the struggle for independence. He campaigned in every part of the United States, from the far north to the deepest south. His skills as an organizer played a major role in the success of the march to Yorktown, and in the aftermath of that victory his diplomatic skills helped to keep the army together until peace was confirmed.

SOURCES

Benjamin Lincoln

The Siege of Charleston

Benjamin Lincoln Papers

Wikipedia: Benjamin Lincoln

American War of Independence

American Revolutionary General

Benjamin Lincoln: Major General

Benjamin Lincoln House – PDF File

Continental General Benjamin Lincoln

Benjamin Lincoln, American Revolutionary General