Loyalist in the American Revolution

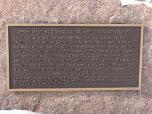

Image: Sarah Kast McGinnis Historical Marker

Bath, Ontario, Canada

Sarah Kast was born near German Flats, New York, in 1713, the daughter of Palatine Germans who were brought to America by England’s Queen Anne in the early 1700s. Her father, Johann Georg Kast, was born in German Palatine; her mother, Anna Margaretha Feg, in Idar Oberstein Germany.

The family arrived in New York City in 1710, and settled in the frontier of the Mohawk River Valley west of Albany, NY, and opened a trading post. Sarah grew up with the Mohawk, sometimes all the children would go to the swimming hole together and play. She knew their language.

One day, a fur trader came riding up. His Irish name was Teady Magin, but he changed it to Timothy McGinnis – easier to pronounce in the English language. Sarah fell in love with him. He was so gentle, so quick to laugh. Her father was a little hesitant to give her away to a man who was not a Palatine, but her mother understood. Timothy was an indentured servant, who worked for the Livingston family south of Albany. He worked off his indenture, and set out to be a fur trapper. Through his travels up and down the river, he acquired a knowledge of the Mohawk language and way of life.

Sarah Kast married Timothy McInnis, an Irishman, in the 1740s, and raised a family of eight children. At some point, Timothy became a captain in the Indian Department: forces of physically strong and fit white men who knew native ways of living, language, and fighting. The soldiers in the Indian Department dressed like natives and fought like guerrillas.

The Mohawk Indians of that region were part of the Iroquois Confederacy, which was first composed of five native nations, and in the 1700’s a sixth, the Tuscarora Nation, joined them, and they became known as The Six Nations. The McGinnis farm was close to the Mohawk Castles (principal villages), and Sarah came to know the Mohawks very well.

The French and Indian War

Timothy McGinnis became acquainted with Sir William Johnson, a British official of the area dealing with the Mohawk. The two men became friends and business partners. Timothy was the representative at Fort Oswego, and they also had land dealings together.

In the summer of 1755, an expedition against the French was planned to expel the French from North America. Albany was selected as the rendezvous, and troops from all the colonies gathered there. Early in August, Sir William Johnson, now a Major General, advanced from Albany to Fort Edward to Lake Saint Sacrement with a force of 2200 colonial troops and 300 Indians, encamped at the head of the lake and renamed it Lake George, in honor of King George II.

General Johnson’s force consisted of about 3000 Colonists and 300 Indians, the latter under King Hendrick, the famous Mohawk sachem and friend of Johnson. Among his officers were General Phineas Lyman, Colonels Ephraim Williams, Timothy Ruggles, and Moses Titcomb; Lieutenant-Colonels Nathan Whiting and Seth Pomeroy; Captains Timothy McGinnis, Philip Schuyler, and Israel Putnam.

In the meantime, Baron Dieskau, a distinguished German officer commanding the French forces in Canada, arrived with 3000 men, one-third of which were veteran regulars from French battlefields. Learning that General Johnson was already at Lake George, and with contempt for his provincial farmers, Dieskau promptly decided to make a sudden attack upon Johnson’s camp the next morning.

The Battle of Lake George

On the morning of September 8, 1755, General Johnson learned of the French invasion and the proposed attack, and sent out a relieving force of 1000 Colonials and 200 Indians, under Colonel Ephraim Williams and King Hendrick. This force fell into an ambush planned by Dieskau, a few miles from Lake George, resulting in severe loss, the killed including Colonel Williams and King Hendrick. This engagement came to be known as The Bloody Morning Scout.

The noise from this engagement gave warning to Johnson’s camp, where breastworks were hastily improvised from logs, fallen trees, and wagons, and placed cannons in advantageous positions. Dieskau followed closely upon the heels of the retreating provincials, and made an afternoon attack on Johnson’s camp, but was checked by the artillery and by the firm stand of the Colonists. The battle raged with varying promise during the afternoon. At last, the Colonials and their Indian allies, confident of victory, charged from their breastworks against the French and forced them to retreat, leaving most of their men dead on the field. This would be called the Battle at Lake George.

On the evening of September 8, 1755, General Johnson sent out an advance party of some 200 men from New York and New Hampshire, under the command of Captain Timothy McGinnis. On their way north, they surprised a party of 300 Canadians, Abenakis, and Caughnawagas on the banks of Rocky Brook, where they had camped for the night. The war party had returned to the scene of the early morning ambush to scalp and loot the dead soldiers and Indians, and were resting with their plunder on the edge of a stagnant forest pool (seven miles from Glens Falls).

Although Johnson’s detachment was outnumbered, they completely surprised the French contingent. McGinnis and his men attacked with such ferocity that most of the scalpers were killed, and the others retreated. Captain Timothy McGinnis died from wounds received in this engagement, and was buried at that site.

The bodies of more than 200 victims were rolled into the pool, and their blood stained the water red, giving the pond its name. It was thick and red for days; tradition says that in later years, it resumed its hue of crimson at sunset and held it until dawn. This engagement was named the Battle at Bloody Pond.

Image: Battle of Lake George

September 8, 1755

By artist Frederick Coffay Yohn

Three engagements – Bloody Morning Scout, Battle at Lake George, and Battle at Bloody Pond – comprise the Battle of Lake George. General Johnson estimated the French loss at more than 500. The Colonials lost over 260, not counting their Indian allies.

These encounters were the first success against the French, and at that point the most important battles fought on New York soil. They were also the first meeting of the yeomanry of the New World with the disciplined troops and experienced officers of the Old World, and this experience helped to develop the confidence that led the Colonists to embark on the great struggle against the British.

Left to run their farm, Sarah Kast McGinnis also went into the fur trading business with her sons-in-law to help support her family. Sarah remained a widow, did her daily tasks, and enjoyed her family, especially her grandchildren.

The Iroquois Confederacy and the Revolutionary War

The Six Nations were badly split by the conflict of the American Revolution. Like most eastern tribes, they tried desperately to remain neutral in the face of threats, bribes, and blatant provocations. As the war progressed, the First Nations chose to support the cause of a distant British king over the close and land-grabbing rebellion. The soldiers of the Indian Department fought along with the natives who were on the British side during the American Revolution.

The Royal government supported several Indian Departments during the Revolution. The Indian Department provided support services in areas that Native cultures mostly lacked, as well as logistical support and liaison to the British Headquarters. Some Indian Department officers led native warriors; some Native war leaders led Loyalist and British troops. They attempted to direct the efforts of their Native allies against targets that London and Quebec found suitable. They also served as translators, guides, gunsmiths, and surveyors or cartographers, as well as couriers and spies.

Sarah Kast McGinnis and the American Revolution

During the American Revolution, Sarah Kast McGinnis, still a widow in 1775, remained loyal to the British. These Loyalists comprised about one-third of American colonists, including officeholders who served the British crown, large landholders, wealthy merchants, Anglican clergy and their parishioners, and Quakers. The Patriots referred to them as Tories. She also used her trading ties to keep the Mohawk loyal as well.

Like other Loyalists, Sarah’s loyalty cost her dearly. In retaliation, members of her family were killed by their rebel neighbors, all their property and their trading post was seized, and Sarah’s house was burned to the ground with her son William inside. Her personal property was taken and sold at auction to Patriot buyers. She became alienated from friends and extended family members.

Sarah (then in her sixties), her daughter and granddaughter were imprisoned at Fort Dayton (now Herkimer, New York), where her granddaughter was treated badly by the guards and died. Her son-in-law Symon DeForest was jailed and died in captivity as well. Another son-in-law escaped from rebel prison in Albany.

Sarah and her daughter were released when General Barry St. Leger and his troops attacked the area. St. Leger’s force, composed mostly of Native Americans and Tories, was intended to come down the Mohawk Valley to meet General Burgoyne at Albany. But Continental troops barred his way to Albany, and he laid siege to Fort Dayton. When St. Leger’s Native American allies heard that a Continental force under Benedict Arnold was moving to relieve Fort Stanwix, they deserted the British, and St. Leger was forced to make a retreat to Canada.

Sarah and her family escaped to Fort Stanwix, with only the clothes on their backs, and when General St. Leger retreated to Oswego and then to Canada, they went, too. In August 1777, Sarah and her family arrived in Canada at a British fort on Carleton Island, southeast of Kingston on the St. Lawrence River; she was 64 years old, but safe.

Image: Lake George Monument

This monument stands on the site of the second engagement of the Battle of Lake George (1755). It illustrates Mohawk chief King Hendrick demonstrating to his friend General William Johnson the danger of dividing his favors. The monument was erected by the Society of Colonial Wars in the State of New York.

After the Battle of Oriskany in August 1777, the Mohawk were still allies of the British, but they had lost a large number of their warriors in that battle. The British had asked them to fight like white men, and many were killed. They didn’t want to fight alongside the British anymore, but to fight as they had in the past, as warriors using Mohawk ways.

In the winter of 1777, at the request of British authorities, Colonel Daniel Claus, a family friend and the Superintendent of Indians, asked Sarah to return to New York to live with the Mohawk. She was well-versed in the Mohawk language and knew well their way of life. The Americans were trying to coax the Mohawks into coming over to the Patriot side, and officials wanted Sarah to persuade the Mohawk people to remain loyal to King George.

Sarah went alone to Niagara on a British ship, and then through the snow in the dead of winter to a Cayuga village. It was all virgin forest she had to cross, from Canada to the Mohawk Castle (principal village). There were lakes and rivers and streams to be crossed. When she arrived, she saw many old Mohawk friends, and they greeted her warmly.

The natives showed her a wampum belt they had received from American General Philip Schuyler. Sarah told the Indians that it was an evil message and to bury it. Sarah spent the winter near Genesee, New York (south of Rochester), calming the Mohawk and keeping them loyal to the British. She returned to Canada in the spring of 1778.

Claus asked Sarah to go back to the Mohawk Nation in the fall of 1779. Her son George, a lieutenant in the Indian Department, came with her. She went to try to save the Mohawk from the terrible fate met by other natives who didn’t heed her advice and leave. She left the safety of Canada, and arrived again in New York State where the Revolutionary War was still going on. During this visit, George was wounded in the Battle of Stone Arabia in 1780.

When they arrived, Sarah was greeted with joy, and a meeting was called to hear what she had to say and to decide what to do. As a result of her visit, many of the Mohawk people came to Canada, where their ancestors still live, and where they were at least safe from slaughter and the burning of their homes.

The natives of the Iroquois Confederacy had begun the war neutral, and ended it driven from their ancestral lands, bitterly attacked by the Continental Congress, and largely betrayed by the British they had so long supported. Sadly, the Natives who supported the Patriots generally came to the same end.

After the end of the Revolutionary War, Sarah moved to Upper Canada with other Loyalists. She petitioned the British government for land and money to cover her losses during her trips to New York. For all her loyalty to the British Crown, Sarah received a small amount of money, but no land grant (to which, as a Loyalist, she was entitled) nor other recognition.

Sarah Kast McGinnis died September 9, 1791, at the home of her grandson Lieutenant Timothy Thompson in Fredericksburg Township, near Napanee, Ontario. She was buried near Bath, Ontario. She was 78 years old.

In 1998, a certificate was finally issued, making Sarah Kast McGinnis an official United Empire Loyalist.

SOURCES

Fort Dayton

Fort Stanwix

Bloody Pond

Forts, Tales, and Legends

Lake George in the American Revolution

French & Indian War: Battle of Lake George

Sarah was my great-great-great-great-great-great-great aunt. I descend from her sister Elizabeth Kast who married Nicholas Mattice II.

I am diect descendent via her grandchildren who moved to South Ontario. Her granddaughter married George Hopper. My dad wad Garnet Hopper born in Wallaceburg, Ont in 1921 to a farming family, gis mother was Mary Taylor – also from Wallaceburg. The Taylors and Hoppers live in around the area today. My grandfather’s brother married my grandmother’s sister

Fascinating history!

I’m confused by a sentence that may contain a typo: “As a result of her visit, many of the Mohawk people came to Canada, where their ancestors still live, …”

It seems that the final phrase in the quoted sentence should be either A:”where their descendants still live” or B: “where their ancestors lived …”.

I am also a direct descendant (8 x’s Granddaughter of Sarah – and am now very happy to understand my fascination with Indians. We are a family of really strong women!

Many errors within this narrative; who might have written it? Benedict Arnold relieved the garrison at Fort Stanwix only after the ambush at Oriskany, when the English allies of Indians and tories had fled the field. Marinus Willett and a detachment from the fort virtually destroyed the indian camps and the Tories’s camps while the battle of Oriskany was in progress. When the combatants returned they found their possessions had disappeared and the English under St Leger retreated to Fort Oswego. The indians became fearful of helping the British and left the area.