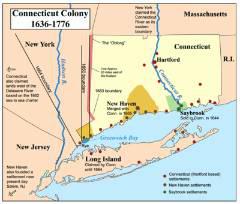

One of the Thirteen Original Colonies

The Colony of Connecticut included all of the present State of Connecticut and a few townships on the shore of Long Island Sound. The Dutch claimed the territory and erected a fort on the Connecticut River in 1633. A number of Massachusetts traders settled at Windsor in 1633. Saybrook, at the mouth of the Connecticut, was settled in 1635. A great many emigrants came from Massachusetts in 1636, the principal leader being Thomas Hooker.

Dutch, Pilgrims and Puritans

The people of Massachusetts were not long in casting their eyes westward from their own barren coast to the fertile valley of the Connecticut River. That knowledge had come early to the Dutch, who had planted a blockhouse, the House of Good Hope in 1633. Plymouth Colony, searching for new trading opportunities, sent William Holmes, who sailed past the Dutch fort and took possession of the site of Windsor.

The territory was also claimed by English lords, Saye and Brooke, who claimed to have obtained from the New England Council a grant of land extending west and southwest from Narragansett Bay. The lords sent over twenty servants, known as the Stiles party. Thus by autumn 1635, there were four sets of rivals claiming the land along the Connecticut River: the Dutch, the Plymouth traders, various emigrants from Massachusetts Bay, and the Stiles party.

Father of Connecticut

In 1630, Thomas Hooker, a zealous Puritan minister in England, was ordered to appear before the high court to answer charges of nonconformist preaching, and instead fled to Holland. Dissatisfied with the state of religion in the Netherlands, Hooker returned secretly to England, and prepared to travel with his family to the New World.

In July of 1633, Hooker and his family boarded the Griffin to sail for Massachusetts. Also aboard the same ship were Puritan preachers Samuel Stone and John Cotton. The Griffin docked at Boston in September, after an eight week journey, and Hooker and Stone went to Newtown, now Cambridge, where a group of his former parishioners had settled.

On the 11th of October, Thomas Hooker and Samuel Stone were chosen as the Pastor and Teacher of the Church of Newtown. John Cotton became the Teacher of the Boston church. The church led by Hooker and Stone prospered, and one of the church’s leading members, John Haynes, was later elected governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

But Hooker and the members of his church soon became restless. The current governor of the colony, John Winthrop, believed in the government of the many by the few, and he had influenced the Bay colony to create freemen out of the citizens very slowly, and to limit voting rights to members of the church. Hooker couldn’t agree to such a policy.

A controversy ensued between him and the governor. Disappointed by of the rigidity of the Massachusetts system, to Winthrop he wrote that, “In matters which concern the common good, a general council chosen by all, to transact business which concern all, I conceive most suitable to rule and most safe for relief of the whole.”

On May 31, 1636, Reverends Thomas Hooker and Samuel Stone led a company of one hundred men, women, and children through the wilderness. Their followers consisted of their families and their congregation. They drove before them one hundred and sixty head of cattle. The cows of the herd, pasturing in grassy savannas on the way, gave them an ample supply of fresh milk.

They had no pathway, and were guided only by a compass. Through thickets and morasses, and over streams they made their way, clearing away here with axes, making causeways and bridges there with felled trees, and resting in shady groves.

The women and children were conveyed in wagons drawn by oxen, and Mrs. Hooker, who was an invalid, was carried on a horse litter. It took them a fortnight to journey a hundred miles. It was ended on the fourth of July, when they stood on the beautiful banks of the Connecticut River, a site which they named Hartford, after Stone’s birthplace in England.

Image: Hooker Reaches the Connecticut River

There Hooker undertook once again the work of establishing a new community and church. Some of the newcomers settled at Wethersfield, and others went further up the river and founded Springfield. Within a year, eight hundred people had found their way into the valley.

The First Written Constitution

The towns settled by Hooker and his followers, along with scattered settlers in the area, banded together and adopted the name of the Connecticut Colony. In 1639, they drew up a written constitution, the first ever framed by a body of men for their own government.

Hooker was one of the drafters of this constitution, known as the Fundamental Orders. It was modeled after the government of Massachusetts, with one huge exception—it gave the right to vote to all freemen, not just church members.

This constitution, which for more than a century and a half underwent little alteration, provided for two annual general assemblies—in April and September. Each town sent deputies to the assemblies. In April, the officers of the government were to be elected by the freemen, and to consist of a governor, deputy-governor, and five or six assistants.

It also established a General Court with legislative, judicial, and administrative powers, thus becoming one of the birthplaces of modern democracy and a prototype of the present government of the United States. No mention whatever was made of the British government or of any allegiance to the king. This constitution, with a few alterations, was in force for one hundred and eighty years.

Thomas Hooker had finally found his place in the world. He remained a religious and governmental leader in the Colony for the remainder of his life. Thomas Hooker died a victim of an epidemic sickness on July 7, 1647.

The Pequot War of 1637

Native Americans of the Pequot tribe killed a Virginia trader on the Connecticut River, and John Endicott marched against them with a body of soldiers. The Pequot refused to turn the guilty party over to the English, and Endicott burned two of their towns and destroyed their crops.

The following spring, a company of about eighty white men, accompanied by Indian allies of the Narragansett and Mohegan tribes, surprised the enemy at daybreak one morning in May, and slew more than six hundred.

A few months later another battle was fought, and the Pequot power was utterly broken. The whole tribe was practically exterminated, which cleared away the last obstacle to the expansion of settlements in the Connecticut River Valley. For forty years afterward New England was free from wars with Native Americans.

A Royal Charter

The people of Connecticut occupied their land for many years without any title to it, but in 1662 John Winthrop Jr. secured a royal charter for Connecticut from Charles II, the most liberal that had yet been given. The only restriction was that the laws should not conflict with the laws of England.

The charter included the New Haven Colony, and at length they consented to become a part of Connecticut. The younger Winthrop became the leader of the colony, as his father had been in Massachusetts, and he held the office of governor for many years.

The Charter Oak

In December 30th 1686, Sir Edmund Andros landed at Boston as Governor of all New England, appointed by the new king, James II. In the autumn of 1687, Andros went to Hartford and entered the House of Assembly, which was then in session. He demanded the charter of Connecticut, and declared the colonial government be dissolved.

Reluctant to surrender the charter, the assembly debated until evening, when candles were lighted. Suddenly, at a signal, all were blown out. When they were re-lighted, the charter was gone. A citizen had slipped out and hidden the paper in the hollow of an old oak tree. Then he returned and took his place among the members. Andros fumed and raved, but went back to Boston empty-handed.

Sir Edmund Andros, however, assumed the government, which he administered until the dethronement of James II in 1689, and Andros lost all of his power. The charter was taken from its hiding place, the assembly was convened, and the records of the colony were once more opened. The old oak was preserved until it literally disintegrated in the nineteenth century.

SOURCES

Connecticut

Connecticut Colony History

New England Colonies: Connecticut

Society of Colonial Wars in Connecticut