Mende Africans of the Ship Amistad

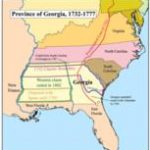

Despite strong opposition, an illegal slave trade still flourished in certain areas of the world during the first half of the nineteenth century. Africans captured by slave traders were taken to Cuba where they were confined in holding pens in Havana and then sent to work at sugar plantations on the island. Between 1837 and 1839, twenty-five thousand Africans were kidnapped and brought to Cuba. In February 1839, six hundred people from Sierra Leone, or as they called it, Mendeland, were captured and brought to the island nation.

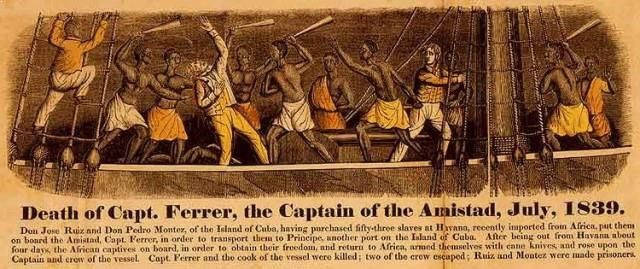

Staged by Joseph Cinque and his fellow captives.

This excerpt from the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History explains further:

Most of the Amistad (which means friendship in Spanish) captives were Mende from Sierra Leone and Liberia in West Africa. Today, the Mende, the most numerous cultural group in Sierra Leone, number over 1.5 million people, with 60 independent chiefdoms. Among the Mende – primarily rice farmers living in small rural villages – all women become social beings by means of initiation into the Sande (or Bondo) society men belonged to the powerful Poro society. This initiation provides the moral base for an ordered adult life, transforming children into adults. Initiation into these and similar societies gives their members social identities and a shared understanding of the wider world occupied by the living, the dead, and the gods.

The Amistad captives held this identity and understanding, both in common. … Most of the Amistad captives were young men and girls, abducted precisely because as healthy young adults they were more likely to survive the cruel Middle Passage from Africa to the Caribbean and to fetch high prices at auction. Since all of these young men and women had been recently initiated into one of these societies, the values, power, and sense of unity the societies imparted were fresh in their minds. … Ironically, the qualities that made the captives suitable cargo and slaves also made them more likely to act in concert and revolt.

Two Spanish planters purchased the Africans for $450 each on June 26, 1839 and gave them false papers and Spanish names. On June 28, the Spanish ship Amistad – a 200-ton cargo schooner built in Baltimore – sailed from Havana, Cuba with forty-nine young men, one boy and three young women. Their destination was Puerto Principe, Cuba, where they would be subjected to a lifetime of slavery on sugar plantations.

Amistad Mutiny

Four days out of port, the forty-nine Africans picked their locks and slaughtered most of the crew. Led by Sengbe Pieh (known in America as Joseph Cinque), took control of the vessel and ordered the three crewmen who had survived to sail toward Africa. Although the ship sailed east during the day, at night, its course was altered to the northwest, toward United States.

Slave Ship in American Waters

Finally, with supplies exhausted and rigging shredded, the Amistad entered the waters of Long Island Sound on August 24, 1839 and sent a shore party to get provisions. By then, ten of the Mende had died – two during the revolt, the rest from thirst or disease.

Amistad Capture

The U.S. Navy crew of the U.S.S. Washington captured the Amistad the following day and towed the vessel into the harbor at New London, Connecticut. At a judicial hearing held on the U.S.S. Washington on August 27, 1839, Federal District Judge Andrew Judson ordered that Cinque and the others must stand trial for murder and piracy at the next session of the Circuit Court, due to open on September 17 at Hartford, Connecticut. The Africans were consigned to the county jail in New Haven to await their trial. A primary issue was whether the Mende would be considered slaves or free.

Well-known New York abolitionist Lewis Tappan formed the Friend of Amistad Africans Committee in September 1839 to aid the young captives. In October 1839, Professor Josiah Gibbs found an interpreter, and the Africans were finally able to tell their story. Connecticut citizens began teaching the captives the English language. Cinque and his fellow Mendeland captives filed charges of assault and false imprisonment against the men who had purchased them in Havana.

The Trials

There were two Amistad trials, one criminal and one civil. On September 19, 1839, criminal charges – murder, mutiny, and piracy – were heard in the District Court by Justice Smith Thompson of the U. S. Supreme Court. The judge ruled that the court had no jurisdiction over the charges; the alleged crimes had been committed on a Spanish ship in Spanish waters and were therefore not crimes punishable under U. S. law.

The Amistad civil trial began January 8, 1840, presided over by Judge Andrew Hudson. On January 15, 1840, the Court ordered the Africans be turned over to the President Martin Van Buren to be returned to Africa. The case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

A leader in the Farmington abolitionist movement, Williams had the carriage house on his property rebuilt as dormatories for the Mende, who lived here about eight months.

United States v. The Amistad

Friend of Amistad Africans Committee persuaded Former President John Quincy Adams to argue the case before the Supreme Court. He reluctantly agreed:

The world, the flesh, and all the devils in hell are arrayed against any man who now in this North American Union shall dare to join the standard of Almighty God to put down the African slave trade; and what can I, upon the verge of my 74th birthday, with a shaken hand, a darkening eye, a drowsy brain, and with my faculties dropping from me one by one as the teeth are dropping from my head – what can I do for the cause of God and man, for the progress of human emancipation, for the suppression of the African slave-trade? Yet my conscience presses me on; let me but die upon the breach.

On February 22, 1841, the Supreme Court began hearing the Amistad case, and Adams fought passionately for the captives’ freedom. On March 9, 1841 the decision came down. By a single vote, the High Court declared the Africans had been illegally enslaved and declared them free people with permission to return to their homeland.

Associate Justice Joseph Story delivered the Court’s decision, which reads in part:

The view which has been thus taken of this case, upon the merits, under the first point, renders it wholly unnecessary for us to give any opinion upon the other point, as to the right of the United States to intervene in this case in the manner already stated. We dismiss this, therefore, as well as several minor points made at the argument. …

Upon the whole, our opinion is, that the decree of the circuit court, affirming that of the district court, ought to be affirmed, except so far as it directs the negroes to be delivered to the president, to be transported to Africa, in pursuance of the act of the 3rd of March 1819; and as to this, it ought to be reversed: and that the said negroes be declared to be free, and be dismissed from the custody of the court, and go without delay.

The institution of slavery had been challenged for the first time before the United States Supreme Court. Although it would take a Civil War and another 24 years to abolish slavery nationally, in this precedent-setting case the central issue was human rights versus property rights.

Mende Africans Welcomed in Farmington

The village of Farmington, Connecticut took in the Mende refugees while they awaited the raising of funds to procure passage aboard a ship back to Sierra Leone, west Africa. Several buildings in Farmington were used to house and teach the Africans. The upper floor of Union Hall, 13 Church Street, was often rented to both abolitionists and anti-abolitionist groups for meetings. Church women met there in 1841 to sew clothing for the Africans of Amistad.

New Haven, Connecticut

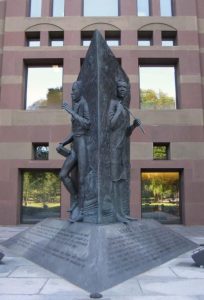

Dedicated in 1992, this three-sided relief sculpture tells the story of Cinque’s journey.

At the previous site of the New Haven Jail, where the Mende were held

until they were freed by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Sailing for Home

In November 25, 1841, the thirty-five Africans who had survived the ordeal sailed toward Mendeland as free people on the ship Gentleman. Along with them were five missionaries who were sent under the auspices of the newly formed Union Missionary Society, a forerunner of the American Missionary Association. The group reached Sierra Leone in January 1842.

Today, the Mende, the most numerous cultural group in Sierra Leone, number more than one-and-a-half million people, with siixty independent chiefdoms.

SOURCES

The Clio: The Amistad Memorial

Austin Williams House: Farmington, Connecticut

Yale Peabody Museum: The African Roots of the Amistad Rebellion

The Amistad Revolt: Historical Legacy of Sierra Leone and the United States – PDF