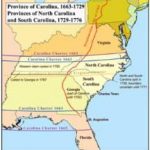

American Patriot and Paul Revere of North Carolina

Image: A wild Banker pony

On the Outer Banks of North Carolina

On the northernmost coast of North Carolina there is a string of sandy islands called the Outer Banks. Betsy Dowdy lived on Currituck Banks there, in the northeastern corner of North Carolina, ten miles south of the Virginia border, bounded by Currituck Sound and the Atlantic Ocean. Betsy had a Banker Pony named Black Bess.

Banker Ponies

On the northernmost coast of North Carolina there is a string of sandy islands called the Outer Banks. In the remote regions of those islands, wild ponies roam free. Banker Ponies are actually horses, but they are referred to as ponies because they are smaller than most horses, standing at about 14 hands.

It is speculated that the herd of Banker Ponies, which currently numbers about 25 to 30, is descended from Spanish Mustangs. Often, when a ship ran aground, its crew would toss livestock and any other animals it may be transporting to the New World overboard in order to float the ship again. Many times, these animals were left behind. The herd ran wild on the island until the 1950s, when they were permanently penned to protect them from the local environment. They are now cared for by the National Park Service.

By the fall of 1775, Virginia’s last royal governor, Lord Dunmore, had worn his welcome out in Virginia. He retreated south from the capital at Williamsburg and captured Portsmouth, then went on to take Norfolk, which was considered a nest of Tories. The harbor there was vital to British control over the colonies. Dunmore wanted to control all of the harbors, in order to stop the colonists from selling their goods.

General George Washington, commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, urged that Dunmore “should be instantly crushed,” lest his forces grow. Washington wrote to the president of the Continental Congress from New England: “I do not mean to dictate, I am sure they will pardon me from freely giving them my opinion, which is, that the fate of America a good deal depends on his being obligated to evacuate Norfolk this winter or not.”

By November, Dunmore was on a campaign to march his troops south and invade northeastern North Carolina. He thought he was making headway against the rebellion by pillaging the plantations of Patriots, winning slaves over to his side, and seizing printing presses. According to contemporary accounts in the Virginia Gazette, after defeating the Patriots at Kemp’s Landing, Dunmore traveled ten miles south to Great Bridge.

After destroying five or six houses, he removed some of the planking, and barricaded Great Bridge on the North Carolina side. Finding resistance increasing, he built a ramshackle fort on the Norfolk side of the bridge – it was dubbed the pig pen by the Patriots – and installed two twelve-pound cannons.

News of these atrocities was slow in reaching North Carolina, because the post road was cut off as well. It was a tense time for the Patriots of Eastern Carolina. Up until that point, North Carolinians didn’t think much about the argument over taxes between the colonies and Britain, but Dunmore’s actions were bringing the war close to home.

On the night of December 6, 1775, the news reached the Dowdy family on Currituck Banks. A neighbor had gone to the mainland on business and brought back the news. Sixteen-year-old Betsy Dowdy overheard the story in all its awful detail, as it was being related to her father. The worst news was that Dunmore had captured Great Bridge. Betsy knew that trade goods – shingles, tar, potash, and turpentine – were transported from the Carolinas through Great Bridge and on to Norfolk for export. The closing of the bridge meant that their livelihood was now cut off.

Worse yet, Dunmore’s men were burning homes and slaughtering the colonists’ livestock and horses. Betsy was shocked to hear that Dunmore’s inhumanity had even extended to the farm animals. She heard her father say, “That renegade will slaughter all our livestock, too. He won’t leave a single Banker pony alive. Dunmore is making sure we have no way to pull our wagons to market.”

The neighbor continued with his tale, reporting that Patriot Colonel Robert Howe was on his way to Great Bridge to try and win it back. But it was the opinion of Mr. Dowdy and his neighbor that it would take a great many more troops than Howe had available to defeat Dunmore. The only Revolutionary soldiers in the area strong enough to stop Dunmore were commanded by General William Skinner fifty miles south in Perquimans County. If someone could take the news to Skinner, maybe he could get to Great Bridge in time to help Howe.

After going back to bed, Betsy tossed and turned. The thought of Lord Dunmore reaching the Carolinas and killing the Banker Ponies haunted her. She had listened to her neighbor express his view that Dunmore would do just that – the ponies were potential remounts for the American militia; Dunmore would kill them all. Betsy loved the wild ponies that roamed the Outer Banks.

Betsy finally made up her mind to go to General Skinner herself. She knew her pony was the fastest on the islands – if any pony could reach Perquimans by morning, it was her Black Bess. She crept downstairs and tiptoed out the door. Without a thought of the cold December air, she vaulted onto the pony’s back and took off for General Skinner’s camp.

Enduring the wintry conditions, Betsy swam across Currituck Sound, rode through the Great Dismal Swamp, Camden, and then Elizabeth City, and then galloped inland more than 50 miles to Perquimans County, before she finally reached the outskirts of Hertford, where General William Skinner and his army of one hundred men were encamped. Paul Revere’s ride was only sixteen miles.

Cold and exhausted, Betsy told General Skinner about Lord Dunmore’s plans. The General called his men to arms, and they marched north to Great Bridge, and they were just in time for the Battle of Great Bridge – a little known but important battle of the Revolutionary War.

The Battle of Great Bridge

Colonel William Woodford, in charge of the Second Virginia Regiment, was gathering forces of Minutemen from Fauquier, Augusta, and Culpepper Counties in the western part of the colony, as well as volunteers from Princess Anne and Norfolk Counties. Among the contingent from Culpeper County was a 20-year-old lieutenant named John Marshall, who was destined to become the most influential Chief Justice in the history of the Supreme Court.

The Virginia Gazette reported “150 gentlemen volunteers had marched to Virginia from North Carolina on hearing of Dunmore’s insolences and outrages.” The Patriots quickly settled in at the North Carolina side of the bridge, and hastily threw up some breastworks for their protection. They exchanged gunfire with Dunmore’s forces, but because of the cannons, declined to attack.

Image: Great Bridge

Currtuck Banks, North Carolina

Early in the morning of December 9, 1775, Dunmore ordered a surprise attack on the Patriots. A British captain led a force of 60 grenadiers and a corps of 120 regulars and militia marching six abreast across the narrow bridge. Seeing no response from the Patriots, the British soldiers wondered if the entrenchments had been abandoned.

On the opposite side, Patriot Lieutenant Travis ordered his men to hold their fire until the British force was within fifty yards. Some 80 patriots sprang up, took aim, and delivered a devastating volley at the approaching troops, quickly thinning their ranks. Their captain fell, only steps from the breastworks. With their commander dead, the regulars ran, dragging the bodies of their dead and wounded back to the bridge.

The British field pieces at the bridge continued to fire, but Patriot reinforcements at the breastwork and the crossfire from their flanking force discouraged any further advances by the British. In twenty-five minutes, Dunmore’s attempt to squash the Patriot buildup near Norfolk was emphatically turned back.

The Battle of Great Bridge was one of the most one-sided contests in the Revolutionary War, with 102 British soldiers killed or wounded, while just a single American suffered a slight wound to his thumb. Dunmore’s army was soundly defeated, halting his invasion of North Carolina.

Great Bridge was the first decisive battle in the South. Volunteer soldiers and militia had withstood an attack by some of the finest professional soldiers in the world, and virtually annihilated them. It was also a battle where riflemen played a very important role. Dunmore’s casualties would undoubtedly have been much less had Woodford’s entrenchments not contained many riflemen. It was a small but strategic victory.

After the battle, Dunmore and his men retreated to Norfolk, but he was unable to gain any support from either those still loyal to the crown or the slaves he had tried to turn against the colony. The victory also secured the passage between the colonies of North Carolina and Virginia.

Norfolk was captured by the American troops on January 1, 1776. Colonel Woodford reported to Edmund Pendleton, president of the Convention at Williamsburg, that he and Colonel Robert Howe were in complete command in Norfolk with 1275 men, and that the Tories and their families had moved to Dunmore’s ship, the HMS Otter, in the harbor.

The victory by the Continental Army was responsible for removing Lord Dunmore and any other vestige of British Government in the Colony of Virginia during the early days of the American Revolution, seven months before the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The war would virtually come to an end some 50 miles away at Yorktown on October 19, 1781, when General Charles Cornwallis surrendered to General George Washington and his allied troops.

SOURCES

Fearless Women Riders

Battle of Great Bridge

The Battle of Great Bridge

The Legend of Betsy Dowdy

The Battle of Great Bridge: December 9, 1775

The Battle of Great Bridge; A New Beginning for the Old Dominion

Writing An Independent Spirit: The Tale of Betsy Dowdy and Black Bess