Thirteen Colonies

Image: Oglethorpe and the Indians

From the Frieze of American History

In the Capitol Rotunda

Washington, DC

In the 1730s, England founded Georgia, the last of its colonies in North America. The project was the brain child of James Oglethorpe, a former army officer and a member of Parliament. He was concerned about the atrocious and crowded conditions in the debtor’s prisons, and resolved to ship the inmates to America where there was plenty of room.

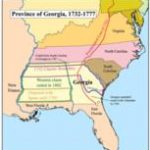

Georgia, named for England’s new King, would also provide a refuge for persecuted Protestants, and a military presence between the other colonies, especially South Carolina, an increasingly important colony with many potential enemies close by. These enemies included the Spanish in Florida, the French in Louisiana and along the Mississippi River, and their powerful Indian allies.

Oglethorpe and the Trustees

Twenty trustees received funding from Parliament and a charter from King George, issued in June 1732. The charter granted the trustees the powers of a corporation – they could elect their own governing body, make land grants, and enact their own laws and taxes. Since the corporation was a charitable body, none of the trustees could receive any land from, or hold a paid position in, the corporation.

Oglethorpe was chosen governor. He traveled to America with thirty-five families, arriving in the spring of 1733. The land was inhabited by Native Americans, primarily the Creek and the Cherokee. Oglethorpe bought the land from the Indians, and retained their friendship from the start. On one of his visits to England he took a party of red men with him, entertained them at his country place and presented them at court.

On a bluff overlooking the Savannah River and the sea, he founded the first city and named it after the river. In 1734, the first religious immigrants arrived in Savannah. The Salzburgers, a devout Protestant people, were led by Oglethorpe up the mouth of the Savannah, where they founded the town of Ebenezer. Others came soon after: John Wesley, the founder of Methodism came as a missionary, and a large group of Scottish highlanders.

Since the undertaking was designed to benefit the poor, the trustees placed a 500-acre limit on the size of individual land holdings. People who had received charity and who had not purchased their own land couldn’t sell or borrow money against it. The trustees wanted to avoid the situation in South Carolina, which had very large plantations and extreme differences between the wealthy and the poor.

The trustees didn’t trust the colonists to make their own laws, and therefore didn’t establish a representative assembly, although every other mainland colony had one. The trustees made all laws for the colony. The settlements were laid out in compact and concentrated townships. This arrangement was instituted to enhance the colony’s defenses, but social control was another consideration. They prohibited the import and manufacture of rum and Negro slavery, hoping to encourage the settlement of English and Christian people.

Georgia’s first year, 1733, went well enough, as settlers began to clear the land, build houses, and construct fortifications. Those who came in the first wave of settlement realized after the first year that they would be working for themselves.

Meanwhile, Oglethorpe, who went to Georgia with the first settlers, began negotiating treaties with local Indian tribes, especially the Upper Creek tribe. Knowing that the Spanish, based in Florida, had great influence with many of the tribes in the region, Oglethorpe thought it necessary to reach an understanding with these native peoples if Georgia was to remain free from attack, and Indian trade became an important element of Georgia’s economy.

Unhappy Colonists

Before long, the settlers began to grumble about all the restrictions imposed on them by the trustees. Most of those moving to Georgia after the first several years were from other colonies, especially South Carolina, and viewed restrictions on the size of individual land holdings as a sure pathway to poverty.

In 1745, after twelve years as governor, Oglethorpe returned to England bearing the colonists’ demands. They wanted to be able to have alcohol and slaves, to participate in their own government, and demanded land reform. They were successful. Alcohol was allowed into the colony because it was thought that the importation of alcohol would improve trade. There was strong opposition to slavery, particularly from the religious immigrants, but they were in the minority.

In 1747, the trustees yielded to the general demand and admitted slavery in the colony. Other rules caused discontent, and many settlers moved away. The population appeared to be at a standstill, and finally the trustees surrendered their rights to the crown. In 1749, Georgia became a slave colony.

A Royal Colony

Georgia became a royal colony in 1752. The trustees were unable to establish self-government and gave up before the 21 year charter had expired. Freemen were given the right to vote (unless they were Roman Catholics) and the people elected an assembly. The governor was appointed by the king. More liberal laws followed, and prosperity increased.

Georgia grew to be more like the other colonies. It had grown quickly after the release of restrictions, though by the time of the American Revolution it was still the least populated. Georgia was still mostly wilderness, but Savannah was important. Slaves constituted half of the population, and there were a few rich planters, but most of the people were small farmers.

The English church was the state church after Georgia became a royal colony, but religious freedom was granted to all Protestants. At first, colonists believed that silk would be an important product of Georgia, since the mulberry tree, which furnishes the natural food of the silkworm, grew wild in Georgia. However, no one was able to succeed at the business. The chief products were rice, indigo, lumber, and fur trade with the Native Americans.

Women in Georgia Colony

Women were important in the settlement of colonial Georgia from its very beginning in 1733. The founding Trustees understood “how necessary a Part Women are in a family,” and wanted them to fulfill their traditional roles. Throughout the colonial period women migrated and settled with families and religious groups, or sometimes as individuals seeking a new start.

Women came as wives, mothers, daughters, or sometimes alone as indentured servants or slaves. They were English, Salzburger, German, Scots, Irish, Sephardic Jews – and after 1750, Africans. Native American women also became part of the colonial fabric. The scarcity of women in the Georgia colony resulted in frequent intermarriage between settlers of different ethnicities.

In the early years, land was granted to males and could be inherited only by males. Land belonging to male colonists who died without male heirs reverted to the trustees for re-granting to other male citizens. The colonists protested this policy. Men wanted their wives and daughters to inherit their land – a man “could never enjoy any peace of mind, for the apprehension of dying there, and leaving his child destitute and un-provided for, not having the right to inherit or possess any part of his real estate.”

From the beginning, the trustees made exceptions, and gradually began to change the policy to allow widows and daughters to stay on their land. Early misgivings about female colonists began to fade. Another protection that some women used in Georgia’s royal period was the pre-marriage agreement, which set a woman’s property aside in a trust to which her husband had no access. The woman kept the right to the property she brought into a marriage, including the sole right to sell it and to choose her heirs.

SOURCES

Georgia

Wikipedia: Georgia

The Colony of Georgia

Women in Colonial Georgia