Early Underground Railroad Sites

The Underground Railroad did not only travel North, away from the plantations of the South to freedom. For almost two centuries before the Civil War, runaway slaves in the colonies of Georgia and Carolina fled south into Florida. From a militia post where freed slaves helped defend St. Augustine against the advancing British to South Florida, some runaways left American soil for freedom on Caribbean islands.

Leader of the Florida Seminoles who fought against the United States during the Second (1835-1842) and Third (1855-1858) Seminole Wars

Fort Mose – First Underground Railroad

Don Pedro Menendez de Aviles founded the town of St. Augustine on the northeastern edge of the Florida peninsula in 1565; it is the oldest European city in what would become the United States. Both enslaved and free African artisans arrived aboard ships to help build and maintain the town; they formed twelve percent of the population, one of every five was a free person. They came with skills learned in their homeland – blacksmithing, carpentry, and cattle ranching.

African-born black slaves from the American colonies of Carolina and Georgia escaped to freedom among the Spanish living at St. Augustine as early as 1687. Courageous Africans and Indians shuttled the runaways on their way southward. Battling slave catchers and dangerous swamps, the Africans helped establish the first Underground Railroad, more than a century before the American Civil War.

Home to freed slaves near the Spanish settlement of St. Augustine, Florida

So many fled here that, in 1693, the Spanish settlement at St. Augustine began freeing the runaway slaves if they agreed to protect the northern border of the town from the British and convert to the Catholic faith. The Spanish were glad to have skilled laborers, and St. Augustine’s weak military forces welcomed the freedmen to their ranks. In 1738, the Spanish Governor established a fortified town – Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose – for the black citizens of St. Augustine. Former fugitive slaves inhabited the fort ‐ better known as Fort Mose (Moh-say) – making it the first free community of ex-slaves in North America.

Approximately one hundred Africans lived at Fort Mose, forming more than twenty households, blending their Spanish and African cultural traditions. In defending their freedom and Spanish Florida in the middle decades of the 18th century, the black inhabitants of Fort Mose played a significant role in the conflicts between Britain and Spain in the Southeast.

Negro Fort

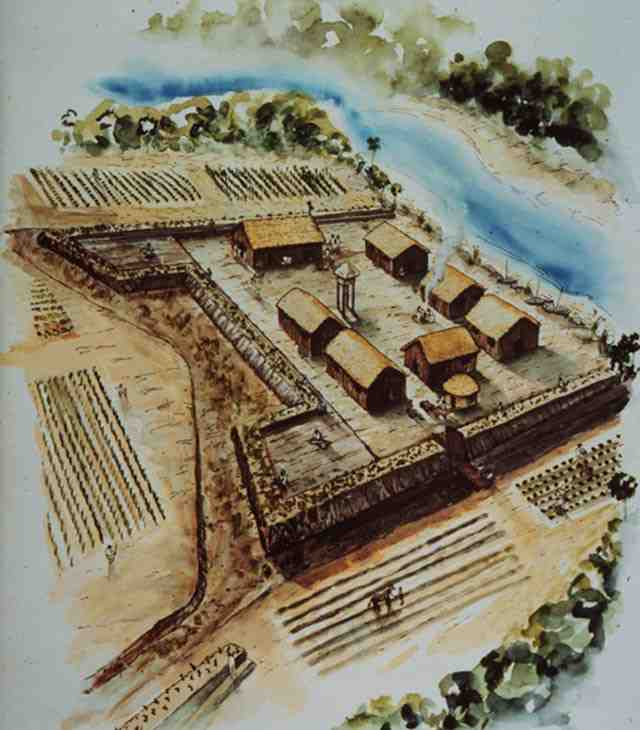

Across the state from Fort Mose, in the Florida panhandle, Franklin County boasts two hundred miles of sandy beaches on the Gulf of Mexico. In the northwestern part of that county, fifteen miles from the mouth of the Apalachicola River, stood Negro Fort, a symbol of the strong relationship between runaway slaves and Seminole Indians in Spanish Florida. In its official history of the fort, the National Park Service describes it as a ‘precursor’ to the Underground Railroad.

During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, slaves who escaped to this part of Florida sought and received refuge from the Seminoles. The Indians welcomed the development of black communities alongside their villages. In return for their protection, the runaways cultivated crops and paid one-third of their produce to the Indians. The fugitives were knowledgeable in the white man’s languages of English, French, and Spanish, and they often acted as interpreters and intelligence agents for the Seminole community.

In 1814, the British arrived at the mouth of the Apalachicola River, under orders of contacting and providing arms and ammunition to the thousands of Red Stick warriors. These natives had fled to Florida after suffering severe losses in the Creek War of 1813-1814. About 30 miles up the Apalachicola River, the British collaborated with the Forbes and Company trading post to distribute military supplies to the allied Red Sticks.

Soon after, the Englishmen began supervising the construction of a fortification. Once completed, the structure held a fighting force of more than 2,000 Red Stick, Seminole, and Choctaw warriors. British officers also assembled a fighting force comprised of 100 African soldiers, most of whom were free black citizens of Florida, though some had been slaves at American plantations in the Southeast.

A regiment of free citizens of Florida and ex-slaves who fought in the War of 1812.

The British remained until May 1815, when they turned the Fort, one cannon, and a large supply of small arms over to the blacks and Indians who had moved into it and cultivated profitable plantations around it. The structure became known as ‘Negro Fort,’ and it served as a “beacon of light to restless and rebellious slaves” from Georgia and Alabama. By 1816, Florida had become a headache for American leaders, mainly because the multicultural, agriculture-based community of about 1,000 escaped slaves and Native Americans was thriving.

Andrew Jackson

In 1816, the American army, under the command of General Andrew Jackson, constructed Fort Scott on the Flint River to protect the border between Georgia and Florida. Jackson was desperate to eliminate Negro Fort. In a letter to Commander Edmund Gaines ordering an assault, Jackson was very clear about his feelings towards the fort:

I have no doubt that this fort has been established by some villains for the purpose of murder, rapine, and plunder, and that it ought to be blown up regardless of the ground it stands on. If you have come to the same conclusion, destroy it and restore the stolen Negroes and property to their rightful owners.

Battle of Negro Fort

As a pretext that they were testing a supply route to bring goods from New Orleans to Fort Scott in Georgia via the Apalachicoa River, Jackson’s men traveled up the Apalachicoa River, passing the Negro Fort along the way. By using this tactic, Jackson hoped to provoke fire to justify his attack. Both Army and Navy troops and gunboats were deployed. They lay waiting for the right moment for weeks, just a few miles upstream from the fort.

Just before dawn on the morning of July 27, 1816, with the Natives and African troops in position across the river, General Andrew Jackson ordered the gun boats to cross the river toward Negro Fort. The fort fired upon the ships, and Jackson gave the order to return fire.

After all the preparations, the engagement between Jackson’s men and the inhabitants of Fort Negro hardly lasted long enough to be called a battle. Only nine cannonballs were fired at the fort that morning. The ninth and final ball was a ‘hot shot,’ which had been held to a flame long enough that it was smoldering. By a stroke of luck, that ninth shot entered into a window of the fort and struck a gunpowder magazine. The explosion that followed was described as “that of a hundred thousand cannons.”

According to official military dispatches, more than 270 escaped slaves and natives died instantly in the blast. An eyewitness account from Colonel Duncan Clinch, who was leading troops from Georgia, described the scene:

The explosion was awful, and the scene was horrible beyond description. Our first care, on arriving on the scene, was to rescue and relieve the unfortunate beings who survived the explosion. The war yells of the Indians, the cries and lamentations of the wounded, compelled the soldier to pause in the midst of victory, to drop a tear for the sufferings of his fellow beings, to acknowledge that the Ruler of the Universe must have used us as his instruments in chastising the blood-thirsty and murderous wretches that defended the fort.

Jackson claimed “self-defense” and “the purest patriotism,” and at the end boasted to his wife, “the enemy is scattered over the whole face of the Earth, and at least one half must starve and die with disease.” According to official U.S. documents, the fort’s surviving black residents were taken to Georgia by the soldiers and returned to slavery.

In his book, Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage William Loren Katz – historian and author of more than forty books on African American history – wrote:

Jackson’s invasion of 1818 did more than take Florida from Spain. It threw the United States into a war to prevent the Black Seminole alliance from disturbing the South’s plantation system. President James Monroe secretly ordered the invasion, and slaveholder General Andrew Jackson conducted it to provide the president ‘plausible deniability.’ Secretary of State John Quincy Adams lied to Congress about the war’s intent, massacres, and clear violation of the Constitution. Only Congress can declare war. Adams further declared opponents of the war were “aiding the enemy” and said Jackson’s atrocities were efforts at “peace, friendship and liberality.” To these leaders Florida’s African Seminole alliance was a dangerous beacon light, refuge and a massive Underground Railroad for their slaves, writes historian William Weeks (John Quincy Adams and the American Global Empire). They feared it would trigger a rebellion that could destroy the US plantation system. Their words and actions as government officials, Weeks writes, remind “historians not to search for the truth in the official explanation of events.”

Black Seminoles

In the late 1600s, a group of African slaves dodged slave hunters and gained freedom by crossing the St. Marys River, which divided Spanish and British colonial territories at that time. This escape route has been described as another segment of the Underground Railroad.

When slaves began to escape to Florida, Indians from the Southeast soon followed. These were remnants of the most resistant tribes – the Creek, Hitichi, and Miccosukee – who had been fighting the Europeans for centuries. Native American refugees from northern wars, such as the Yuchi and Yamasee after the Yamasee War in South Carolina, migrated into Florida in the early 18th century. More arrived in the second half of the 18th century, as the Lower Creeks began to migrate from several of their towns into Florida. Together they became known as the Seminoles.

Like the Spanish, the Seminoles harbored runaway slaves and forged close alliances with the former slaves in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Although most blacks were governed by Seminole chiefs, they were free in every other way. Most lived in their own villages and, as a kind of tax, gave corn to the tribe. Africans taught the Indians to build homes, tend livestock and speak English and Spanish.

The former slaves became farmers, ranchers, cowboys, interpreters, hunters, traders and warriors. Some farmed and traded, building peaceful relations with Indians, slaves, and former masters. Intermarriages were common; the offspring of these unions came to be known to historians as ‘Black Seminoles.’ On several occasions, Seminoles and their African allies banded together in the defense of their homelands.

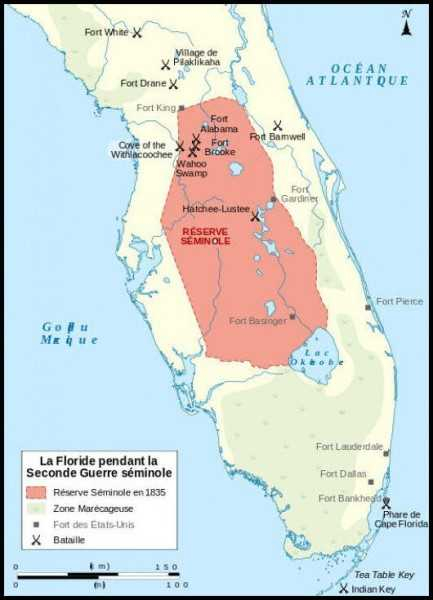

In 1812, a combined force of Africans and Seminoles repelled Georgians known as the ‘Patriot Army’ who intended to capture slaves and seize parts of Spanish Florida for the United States. The American push to acquire Florida caused many hardships for Black Seminoles. After Andrew Jackson’s raid into Spanish Florida (also known as the First Seminole War in 1816-1818), many Africans abandoned their towns on the Suwannee River and took refuge farther south in the remote interior regions of central Florida.

The number of runaway slaves increased when the United States acquired Florida from Spain in 1821. Planters from Georgia and the Carolinas traveled to northern Florida, but some of the people they held in bondage escaped and found refuge with the Seminoles. Article VII of the treaty made at Camp Moultrie in September 1823 compelled the Seminoles to be ‘active and vigilant’ in preventing runaway slaves from entering their territory. Moreover, the treaty required Seminoles to ‘apprehend and deliver’ fugitive slaves to federal agents.

Seminoles and Black Seminoles revolted when American officials attempted to enforce the Indian Removal Act in Florida and relocate their tribe to Oklahoma. In the mid-1830s, Seminoles and their African allies raided U.S. Army fortifications numerous times. They also attacked sugar plantations in East Florida; many of the slaves on these plantations fled during the chaos and joined the Black Seminoles. These events marked the beginning of the Second Seminole War (1835-1842), the longest and costliest American Indian War in U.S. history.

No longer able to find freedom in Seminole Country after the wars, runaway slaves increasingly sought the Underground Railroad as the pathway to freedom on the Caribbean Islands. During the American Civil War, service in the Union Army served that function for black men.

SOURCES

NPS.gov: British Fort

Clio: Battle of Negro Fort

Town of Jupiter: The Forgotten Seminoles – PDF

Fort Mose: America’s Black Colonial Fortress of Freedom

Florida Memory Blog: Florida’s Underground Railroad (Part Three)

Remembering the Battle of Negro Fort, one of the most important and forgotten events in U.S. history