Catharine Parr Traill is important to Canadian history as is her sister Susanna Moodie for authoring a number of books, some which offer the reader a view of early Canadian history. She is not like most women in garden history who tend to be royalty or wealthy with funds at their disposal for grand gardens or greenhouse collections. She is not a plant hunter or a botanist who identifies species and then sends the moverseas to be catalogued and named by men. How then does she fit into a garden history?

Catharine is unique and she belongs in garden history because she has seen a world few of us ever will. She immigrated to Canada in 1832 a time when colonies were small and the land almost untouched by man. She has seen it with eyes of a visitor and eventually a settler who despite great struggles learns to love her new homeland. She was a woman who looked at the details, watched the fringes, enjoyed the tiny pleasures of life whether flora or fauna and recorded her sightings in wonder.

Catharine Parr Traill was one of 6 girls and 2 boys to Thomas Strickland and Elizabeth Homer. The family lived in Suffolk in rural England but were not of the same class as their wealthier neighbours. Thomas educated his children himself and taught them history, geography, maths,theology and the morality of the Church of England. Catharine was the favourite child of her father. Known to the family as Katie, she had a sunny and cheerful disposition that kept her spirits high even during the struggles and great hardships she was to face in Canada. Catharine and her father would go fishing and take long walks together. He pointed out plants and animals during these times and imparted what information he could to her. Books were of great importance to the Strickland family. As young children Catharine and her sisters read novels, poetry, wrote stories and put on plays in the house using the family’s old silks and old court dresses from Queen Anne’s reign. By the 1820’s four of the sisters, including Catharine and Susanna, were published writers of poetry, romantic fiction and children’s stories.

Through her sister Susanna and husband John Moodie, Catharine met Thomas Traill, a friend of Moodie’s for many years. In 1832 Catharine and Thomas married. Both couples had decided to emigrate to Upper Canada (Ontario) with the hope of a better life. Neither husband was well off and unfortunately neither was properly prepared mentally and physically for the backwoods life that awaited them. The Traills left England by cargo ship with Catharine sick on the voyage. Then while in Quebec City she contracted cholera. Thomas went as hore and on his return brought her a bouquet of flowers. The roses, sweet pea and pulmonaria she recognized but not some others. Perhaps it was this moment that inspired Catharine to identify the Canadian species of plants she was to see once on shore in this New World.

They left Quebec City by stagecoach, then boat to Cobourg, and then by wagon to Rice Lake. They took a steamboat from Rice Lake and an oared scow to the town of Peterborough. The last leg of the trip was made by horse-pulled- wagon through the bush where there was no road only a blaze trail “encumbered by fallen trees, and interrupted by cedar swamps, into which one might sink up to one’s knees”. The trip took four months.

The Backwoods of Canada 1836

Thomas and Catharine’s first home was in the backwoods near Lake Kitchiwannoe. The backwoods is filled with bush, and forests of pine, oak, maple and beech. Trees needed to be cleared to set up a home, and the land would be covered with stumps for years to come. It was not a pictures quesetting. It took more money and hard work than realized. Like women before her Catharine may have despaired over her new life, after all she left behind family, some financial security and most importantly her growing career as an author. Catharine looked to the land and took her refuge in flowers – columbine, goldenrod, and hepaticas to name a few.

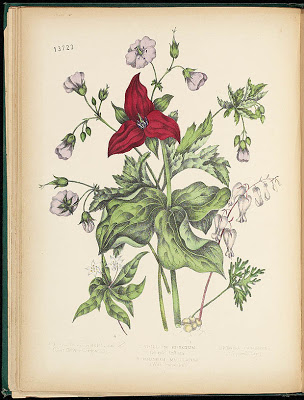

Since her arrival in Upper Canada Catharine collected and studied flowers, grasses, mosses, lichens and ferns. She became a serious student and studied all aspects of a plant; its appearance, its life cycle, its relation to other plants, and even the medicinal and food value. Some of this she learned from the Indian women who lived nearby and some she learned from her only reference book, Frederick Pursh’s Flora Americae septentrionalis (North American Flora), published in 1814. When her own knowledge or Pursh’s book failed her Catherine named the plants herself,

“I consider myself free to become their floral godmother and give them names of my own choosing,”

she wrote. Catharine kept a journal full of notes on plants she found and was trying to identify.

“I am never weary with strolling about,climbing the hills in every direction, to catch some new prospect, or gather some new flowers, which, though getting late in the summer, are still abundant.Among the plants with whose names I am acquainted are a variety of shrubby asters, of every tint of blue, purple, and pearly white; a lilac monarda, most delightfully aromatic, even to the dry stalks and seed-vessels; the white gnaphalium or everlasting flower; roses of several kinds, a few late buds of which I found in a valley, near the church.”

Catharine began a hortus siccus (dry garden) for her sister Eliza living back home in England. In it she described plants, their growth and any “striking particulars”. She learned to dry the plants and collect the seed. Much was sent to Eliza for her interest. Later in time she received a screwpress with which she could press her ferns more effectively.

Thanks Dstinyseatings for the visit !

Yes Tammy, I can not help but admire her resolve and determination with such a difficult life. The life of a pioneer.

Your writing is so entertaining, Patty! I hope you will find that fern for your garden.

Hi Denise. Thanks for checking out this blog. I have never seen a fern with Catharine's name on it so it may take some detective work. Wish me luck.

Patty what a fascinating woman who pioneered plants an animals in the wild.I envy her being able to see so much we have lost.I hope you find the fern.

Hi Donna, This is what I enjoy about looking into these women's lives. While in one respect their lives are so different from our own, they also share so many things in common with ours, like a love of plants and animals. As for the fern, the bit of digging I did has turned up nothing. I think at best I would fine Shield Ferns but not the variety named after Catharine.

She sounds like a bit of a Canadian forerunner of Aldo Leopold. Good post!

Hi Jason, Thanks. I had to look up Mr. Leopold as I have never heard of him. He seems like an interesting fellow, with an avid concern for wildlife and their environment. Nice that his kids followed in his footsteps.

I'm sorry I'm so behind in reading this blog. She sounds intrepid and fearless. I love that there is a fern named after her. It seems fitting to honor her with a plant from her much-loved forests. :o)