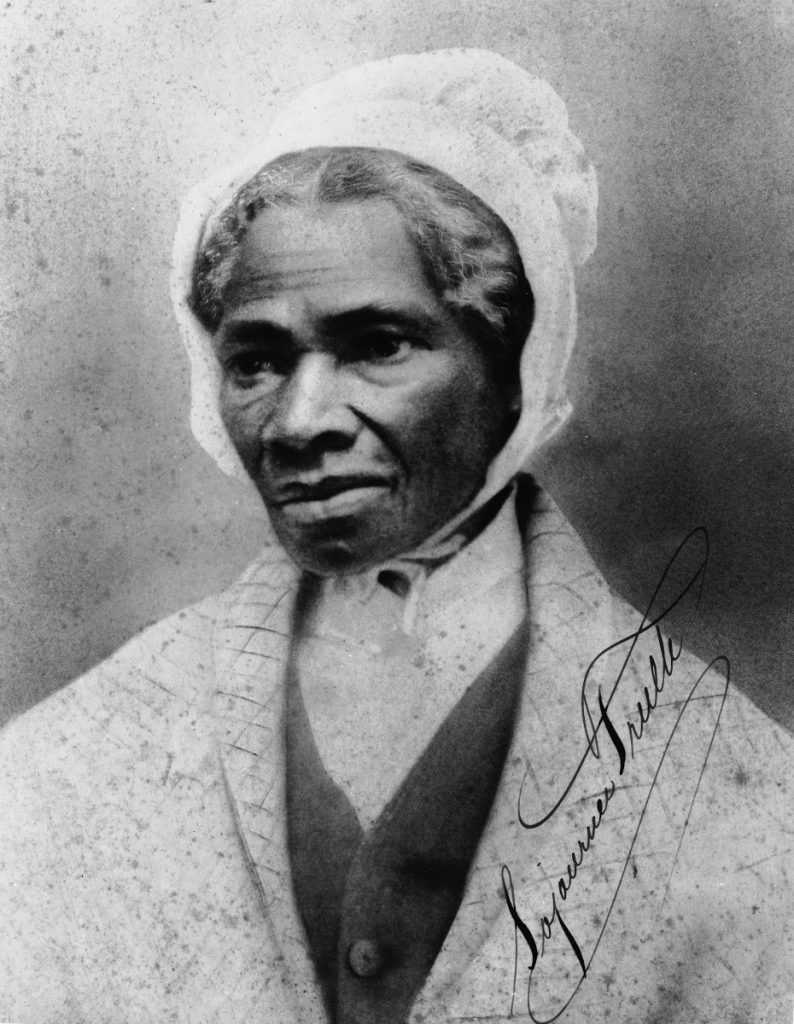

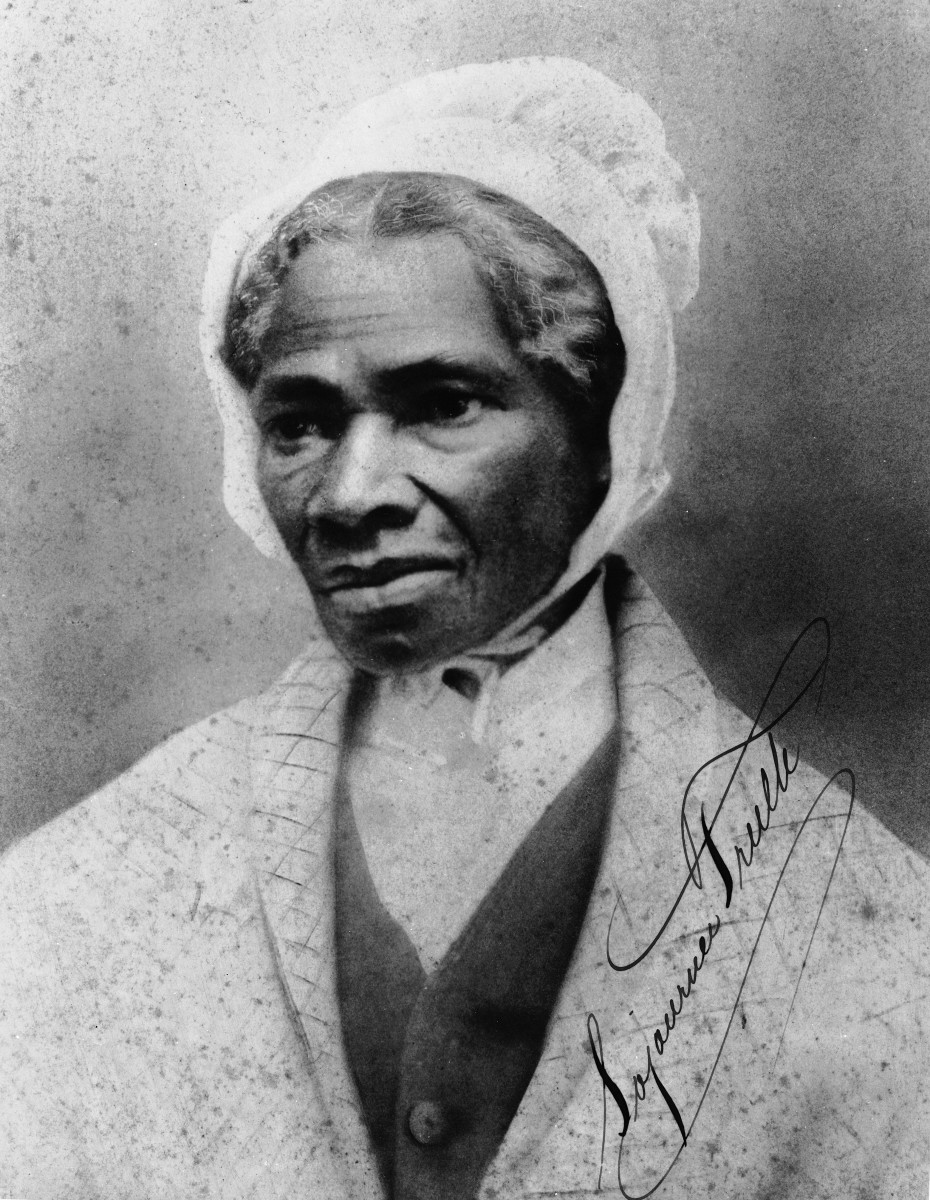

Prominent abolitionist and women’s rights activist

Abolitionist Movement in Philadelphia

In the 1830s, female antislavery societies circulated and gathered signatures on antislavery petitions, held public meetings, organized fundraising events, and financially supported improvements in free black communities. Many of these organizations focused on submitting signed petitions to the U.S. Congress as a top priority in their campaigns to end slavery. Women were not yet allowed to vote; therefore, petition drives were one of the few forms of political expression available to female abolitionists.

Petition campaigns drew women out of their homes and into their neighborhoods where they conducted massive door-to-door campaigns and then sent the signed documents to the U.S. Congress. Between 1834 and 1850, these women sent thousands of these petitions to Washington DC, causing the U.S. House of Representatives to pass a gag rule in May of 1836. They would continue to accept the petitions, but they would not be debated or discussed until an unspecified date.

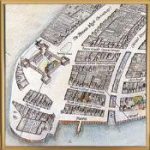

African Americans in Philadelphia

The first blacks in Philadelphia were slaves; approximately 1,500 people lived as slaves in the city during the period slavery was legal. They usually resided with their owners and worked as servants in their shops or homes. In 1780 an abolition law failed to free any existing slaves, but the document banned the slave trade in Pennsylvania and freed children born to slaves once they reached a certain age. When the law was passed, about 800 free blacks and 400 slaves lived in Philadelphia.

Many newly freed slaves and fugitives from the South moved to the city, and by 1820 the city’s African American numbered nearly eleven percent. As the black population grew, so did the hostility of white citizens towards them. During a race riot in 1834, whites attacked and killed African Americans, on the street and in their homes. In 1838 the Pennsylvania legislature passed a law that prevented African Americans from voting. Abolitionists who helped fugitives find their way to freedom were also targets and were prevented from spreading their beliefs to others.

Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women

The first Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women (ASCAW) was held in New York City on May 9, 1837. One hundred and seventy-five women, from ten different states and representing twenty female antislavery groups, gathered to discuss their role in the American abolitionist movement. This assembly represented the first time that women from such a broad geographic area met with the purpose of promoting the antislavery cause.

The delegates to this convention included women of color, as well as the wives and daughters of slaveholders. They were primarily from New England and other northeastern states. Lucretia Mott was chosen as chairperson, and Mary S. Parker served as president of the event. Parker had six vice-presidents: Lydia Maria Child, Abby Ann Cox, Grace Douglass, Ann Carroll Fitzhugh Smith and Sarah Grimke. Mary Grew, Angelina Grimke, Sarah Pugh, and Anne Warren Weston served as secretaries.

Sarah Grimke had asked the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society to send African American delegates, but few of those were blessed with the financial means to travel to New York. Ultimately, only five black women attended that convention; but their presence was crucial to its success. Sarah Grimke and her sister Angelina were daughters of South Carolina slaveholders, Judge John Faucheraud Grimke and his wife Mary Smith Grimke. Both parents came from wealthy planter families, and they moved in the elite circles of Charleston society. Together the couple had 14 children, three of whom had died in infancy. Angelina was the youngest. The Grimke sisters subsequently became Quakers.

The convention provided a means for women from different states and backgrounds to meet in person and promoted increased interactions between black and white women. Antislavery petitions were significant in the movement, and they more than doubled in number that year. These door-to-door campaigns brought the abolitionist agenda to thousands of individuals who might not have been exposed to this information otherwise.

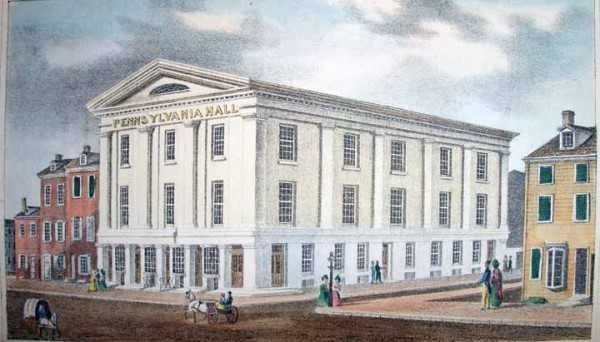

Pennsylvania Hall

This commodious hall was built by the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society in the spring of 1838 because abolitionists, especially female abolitionists, often had a difficult time finding space for their meetings. In the preceding years, the city’s African American population had grown substantially as free blacks and fugitive slaves united with the large Quaker population in the struggle to end slavery.

To finance the construction, members of the Society created a joint-stock company in which two thousand people bought $20 shares; others donated material and labor. The first floor consisted of lecture and committee rooms, as well as a bookstore that sold abolitionist publications. The second floor was devoted to a large hall, with galleries on the third floor.

At the dedication ceremony on Monday, May 14, 1838, letters from abolitionists Gerrit Smith and Theodore Weld, and former president John Quincy Adams were read. Adams wrote:

I learnt with great satisfaction … that the Pennsylvania Hall Association have erected a large building in your city, wherein liberty and equality of civil rights can be freely discussed, and the evils of slavery fearlessly portrayed. … I rejoice that, in the city of Philadelphia, the friends of free discussion have erected a Hall for its unrestrained exercise.

On the same day the Hall was dedicated, Angelina Grimke married Theodore Weld in an unconventional wedding that reflected their abolitionist and feminist beliefs. The cake was made with free produce sugar (not made by slaves), and the bride promised to love and cherish, but not to obey.

1838 Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women

The three-day convention of the 1838 Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women (ASCAW) was scheduled to begin on Tuesday, May 15. That morning notices appeared throughout Philadelphia, calling upon “citizens who entertain a proper respect for the right of property,” and instructed them to “interfere, forcibly if they must, and prevent the violation of these pledges [the preservation of the Constitution of the United States], heretofore held sacred.” Many white residents of the city believed that the abolitionists were encouraging black migration to the area and were responsible for problems between the North and the South.

Venue for 1838 Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women

New building, dedicated May 14, 1838

Burned to the ground May 17, 1838

A crowd of protesters had gathered outside of the hall, but the ASCAW meeting went on as scheduled on May 15. As always, before the meeting began, the members of the convention declared their faith in the fundamental principle of radical abolitionism, namely that slavery was “a sin, and ought immediately to be abolished.” They also resolved to deny themselves “some of the luxuries and superfluities” in which women indulged in order to contribute more liberally to the antislavery cause.

On the morning of the following day, Wednesday, the men who had gathered outside Pennsylvania Hall began “prowling about the doors, examining the gas-pipes, and talking in an ‘incendiary’ manner to groups who collected around them in the street.”

The protestors returned on Thursday morning, May 17, 1838. More meetings of the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women were scheduled, and the members refused to comply with the Mayor’s request to restrict the convention to white women only. Later in the day, the men who surrounded Pennsylvania Hall became more unruly.

That evening, as William Lloyd Garrison was introducing Maria Weston Chapman to more than three thousand attendees, the mob broke into the building. Perhaps they were unsettled by that bold move; whatever the reason, they soon left, only to disrupt the meeting from the outside. Rocks came crashing through the windows while Chapman spoke; the noise from the outside sometimes overwhelmed her voice.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Culture of Philadelphia

Gilder Lehrman Center: The Riots

Slavery in America: Pennsylvania Hall

Gilder Lehrman Center: Pennsylvania Hall

Wikipedia: Pennsylvania Hall (Philadelphia)

Angelina Grimke Weld’s Speech at Pennsylvania Hall

Wikipedia: Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women

Burning of Pennsylvania Hall in Anti-Abolitionist Riot of 1838

History Engine: The Significance of Rhetoric in Antebellum America

Am I Not A Woman and A Sister? The Anti-slavery Convention of American Women 1837-1839 – PDF