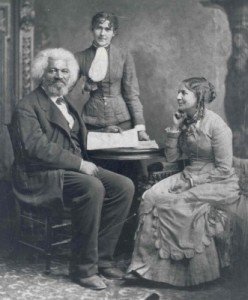

Wife of Former Slave Frederick Douglass

Anna Murray Douglass was an American abolitionist, member of the Underground Railroad, and the first wife of orator and abolitionist Frederick Douglass. Her life illustrates the challenges faced by women who marry famous men.

Early Years

Anna Murray was born free to Bambarra and Mary Murray in Denton, Maryland in 1813. Anna was ambitious; by the age of 17 she had moved to Baltimore and established herself as a laundress and housekeeper and was earning a decent income, especially for someone so young.

Murray facilitated Frederick’s second escape attempt by providing money for a train ticket and a sailor’s disguise. She followed him to New York City, where they were married by the prominent black minister, Rev. J.W.C. Pennington. They adopted the surname Douglass when they moved to a Quaker community in New Bedford, Massachusetts.

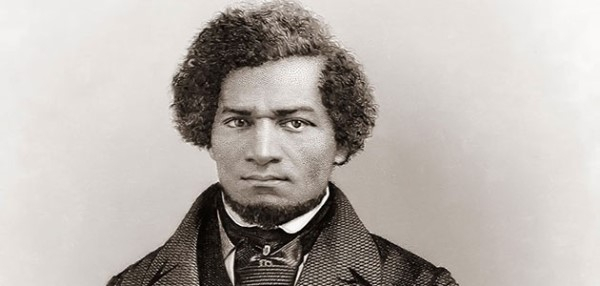

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born into slavery on the Eastern Shore of Maryland in February 1818. His mother died when he was a young child; he did not know his father. At age eight, Frederick was sent by his owner to Baltimore to work as a body servant. Frederick soon recognized the importance of education and taught himself to read and write. At twelve, he bought a book called The Columbian Orator, a collection of political essays, poems, and dialogues that was widely used to teach reading and speaking in the early 19th century.

Anna Murray first met a slave named Frederick Bailey (later Douglass) through mutual friends at the East Baltimore Improvement Society, an organization of free blacks who promoted literacy. The two became fast friends, and Anna agreed to help Frederick escape from slavery.

Marriage and Family

On September 3, 1838, Frederick wore a sailor’s uniform as a disguise and purchased a ticket on a northbound train – all provided by Anna Murray. In less than 24 hours, Frederick arrived in New York City and declared himself free. He sent for Anna, and they married on September 15, 1838; they remained married for 44 years.

After moving to New Bedford, Massachusetts, the couple adopted Douglass as their surname. Anna gave birth to five children in the first ten years of their marriage: Rosetta, Lewis, Frederick Jr., Charles and Annie.

Anti-Slavery Work

Frederick first spoke out against the evils of slavery while living in New Bedford. In the early 1840s the Douglass family moved to a farm in Lynn, Massachusetts, where Anna worked as a laundress and shoe binder. She supported the family while Frederick lectured abroad for two years. She also took an active role in the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society.

Move to Rochester

The family moved to Rochester, New York in 1847 and Frederick began publishing his abolitionist newspaper North Star. Anna prevailed upon her husband to train their sons as typesetters for his newspaper. They bought a house on Alexander Street, and in 1849. Anna supported Frederick’s public career, but his income from his speeches was sporadic, and the family sometimes struggled financially.

Underground Railroad

After the family moved to Rochester, New York, Anna established the Douglass home as a station on the Underground Railroad, providing food, board and clean linen for hundreds of fugitive slaves on their way to Canada. Her daughter Rosetta later wrote that it was not unusual for her mother to be called up at all hours of the night to prepare supper for a “hungry lot of fleeing humanity.”

They moved to a hilltop farm on South Avenue in 1852. Frederick’s business trips kept him away from his family for long periods of time. Anna remained at home caring for their children and tending her garden. She had the reputation of being a model housekeeper who took pride in doing all the housework herself without hired help. Their five children were taught good manners and trained to be self-sufficient and industrious. An excellent money manager, her watchful spending “laid the foundation for [their] prosperity.”

Their Rochester home on South Avenue in Rochester was destroyed by a fire in 1872, and they moved to Washington DC.

He became the best-known African American during his fight for the abolition of slavery.

Frederick Writes about Anna

In his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845), Frederick wrote:

I had been in New York but a few days, when Mr. [David] Ruggles sought me out, and very kindly took me to his boarding-house at the corner of Church and Lespenard Streets. Mr. Ruggles was then very deeply engaged in the memorable Darg case, as well as attending to a number of other fugitive slaves, devising ways and means for their successful escape; and, though watched and hemmed in on almost every side, he seemed to be more than a match for his enemies. …

At this time, Anna, my intended wife, came on; for I wrote to her immediately after my arrival at New York, informing her of my successful flight, and wishing her to come on forthwith. In a few days after her arrival, Mr. Ruggles called in the Rev. J.W.C. Pennington, who, in the presence of Mr. Ruggles, Mrs. Michaels, and two or three others, performed the marriage ceremony, and gave us a certificate. … I had no money with which to pay the marriage fee, but he seemed well pleased with our thanks.

Upon receiving this certificate, and a five-dollar bill from Mr. Ruggles, I shouldered on part of our baggage, and Anna took up the other, and we set out forthwith to take passage on board of the steamboat John W. Richmond for Newport, on our way to New Bedford.

David Ruggles was secretary of the New York Committee of Vigilance, a radical biracial organization to aid fugitive slaves and oppose slavery.

Excerpt from a letter to Anna Richardson dated April 29, 1847, which Frederick wrote from home in Lynn, Massachusetts:

I am once more at home; once more with the wife of my bosom, and in the midst of the dear children of my love. … My dear Anna is not well, but much better than I expected to find her, as she seldom enjoys good health. She feels exceedingly happy to have me once more at home. She had not allowed herself to expect me much, for fear of being disappointed; but she was none the less glad to see me on that account. … Dear Anna and myself are intending to visit Albany in a few days: and we shall then see our only girl Rosetta.

Letter to Thomas Auld September 8, 1848, published in North Star:

I married soon after leaving you: in fact, I was engaged to be married before I left you, and instead of finding my companion a burden, she was truly a helpmeet. She went to live at service, and I to work on the wharf, and though we toiled hard the first winter, we never lived more happily. … So far as my domestic affairs are concerned, I can boast of as comfortable a dwelling as your own. I have an industrious and neat companion. …

Letter to Maine abolitionist Lydia Dennett written April 17, 1857:

Suppose I begin with my wife. I am sad to say that she is by no means well – and if I should write down all her complaints there could be no room even to put my name at the bottom, although the world will have it that I am actually at the bottom of it all. She has the face – I was going to use terms scarcely up to the standard of modern elegance – neuraligia. She has a great deal to do, but little time to do it in, and withal much to try her patience and all her other very many virtues. You have doubtless in your experience, met with many excellent wives and mothers, who have been in very much the same condition in which my wife is. She has suffered in every member except one. She still seems able to use with great ease and fluency her powers of speech, and by the time I am at home a week or two longer, I shall have pretty fully learned in how many points there is need of improvement in my temper and disposition as a husband and father, the head of a family! Amid all the vicissitudes, however, I am happy to say that my wife gives me an excellent loaf of bread and keeps a neat house, and has moments of marked amiability, of all which good things I do not fail to take due advantage.

Late Years

After her youngest daughter Annie died in 1860 at the age of 10, Anna was often in poor health.

In 1872, the Douglasses moved to Washington DC, where they purchased two row houses at 316 and 318 A Street NE. In 1877, they moved to a house called Cedar Hill in the Anacostia neighborhood, which was purchased with money that Anna had saved from her years as a shoe mender. They resided there for the remainder of their lives.

In 1882, Anna Murray Douglass was stricken with paralysis. She died August 4, 1882 at Cedar Hill. She was initially buried at Graceland Cemetery in Washington DC, but the cemetery closed in 1894. On February 22, 1895, she was moved to Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester, New York.

Frederick Douglass was buried next to her after his death on February 20, 1895.

Excerpt from My Mother As I Recall Her written by Anna’s daughter, Rosetta Douglass Sprague, and read before the Anna Murray Douglass Women’s Christian Temperance Union on May 10, 1900 by the author:

Her courage, her sympathy at the start was the main-spring that supported the career of Frederick Douglass. As is the condition of most wives her identity became merged into that of her husband. Thus only the few of their friends in the North really knew and appreciated the full value of the woman who presided over the Douglass home for forty-four years.

SOURCES

NPS.org: Frederick Douglass

Wikipedia: Anna Murray Douglass

Oxford University Press: Anna Murray Douglass

Compiling the Evidence: Frederick Douglass on Anna Murray Douglass