1838 Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women

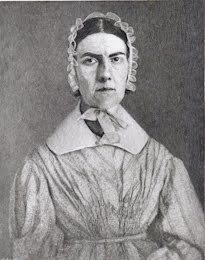

Angelina Grimke Weld’s Speech at Pennsylvania Hall

Inside Pennsylvania Hall, Angelina Grimke Weld took the podium and began her speech in a strong loud voice. Several times during her speech the audience rose to leave, but Weld persuaded them to stay. Her speech went on for over an hour. This is an excerpt from that speech:

Men, brethren and fathers – mothers, daughters and sisters, what came ye out for to see? A reed shaken with the wind? Is it curiosity merely, or a deep sympathy with the perishing slave, that has brought this large audience together? [A yell from the mob without the building.] Those voices without ought to awaken and call out our warmest sympathies. Deluded beings! “they know not what they do.” They know not that they are undermining their own rights and their own happiness, temporal and eternal.

Do you ask, “what has the North to do with slavery?” Hear it – hear it. Those voices without tell us that the spirit of slavery is here, and has been roused to wrath by our abolition speeches and conventions: for surely liberty would not foam and tear herself with rage, because her friends are multiplied daily, and meetings are held in quick succession to set forth her virtues and extend her peaceful kingdom. This opposition shows that slavery has done its deadliest work in the hearts of our citizens.

Do you ask, then, “what has the North to do?” I answer, cast out first the spirit of slavery from your own hearts, and then lend your aid to convert the South. Each one present has a work to do, be his or her situation what it may, however limited their means, or insignificant their supposed influence. The great men of this country will not do this work; the church will never do it. A desire to please the world, to keep the favor of all parties and of all conditions, makes them dumb on this and every other unpopular subject. They have become worldly-wise, and therefore God, in his wisdom, employs them not to carry on his plans of reformation and salvation. He hath chosen the foolish things of the world to confound the wise, and the weak to overcome the mighty.

As a Southerner I feel that it is my duty to stand up here to-night and bear testimony against slavery. I have seen it – I have seen it. I know it has horrors that can never be described. I was brought up under its wing: I witnessed for many years its demoralizing influences, and its destructiveness to human happiness. … I have never seen a happy slave. I have seen him dance in his chains, it is true; but he was not happy. … When hope is extinguished, they say, “let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we die.” [Just then stones were thrown at the windows, a great noise without, and commotion within.]

Grimke Weld did not allow the commotion outside to interfere with her speech. When it finally came to an end, officers of the convention quickly adjourned the meeting. As a show of solidarity, white and black women walked out of the hall arm in arm.

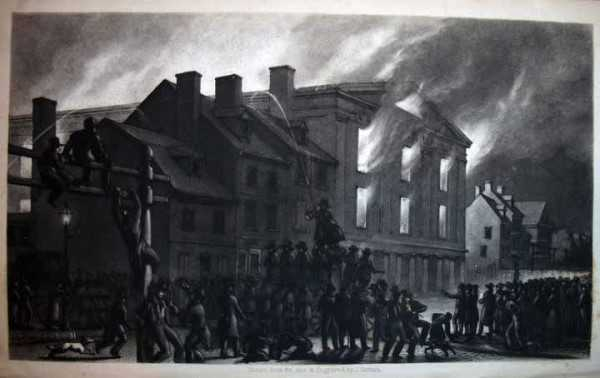

Burning of Pennsylvania Hall

On May 17, 1838, Pennsylvania Hall’s building managers feared that the mob posed a serious threat, and they handed the keys over to the mayor of Philadelphia. The mayor locked the doors and announced to the crowd that the remaining meetings had been canceled. The crowd cheered as he walked away. Soon after, the anti-abolitionists broke into the building, destroying the interior and setting fires in several places.

The mayor returned with the police, but by now the mob, estimated at more than ten thousand people, was out of control. Firefighters arrived at the scene but sprayed only the structures that surrounded Pennsylvania Hall. When one unit sprayed the new building, its men became the target of another company’s hoses. By nine o’clock that evening, the fires had spread, engulfing the entire building in flames.

An anti-abolitionist mob broke into the Hall and set fires in several locations.

On May 17, 1838, only three days after its dedication, Pennsylvania Hall burned to the ground as Philadelphia police officers and firefighters stood by. An official report blamed the abolitionists for the riots, claiming that they incited violence by upsetting the citizens of Philadelphia with their views and for encouraging “race mixing.” A large portion of the merchants in the city applauded the destruction of the building. Although some of the rioters were known, and two or three indicted, the Attorney General never brought them to trial.

Excerpt from Am I Not a Woman and a Sister by Ira V. Brown:

The pretext for the attack on the hall was the charge that it was a “temple of amalgamation,” that is, miscegenation [the mixing of different racial groups through marriage, cohabitation, sexual relations, or procreation]. Newspapers throughout the nation carried reports that white women had been seen walking arm-in-arm with black men in the vicinity of the hall.

Despite the brevity of its existence, Pennsylvania Hall was frequently cited by various racial, ethnic and religious groups that its desctruction proved that they had the right to defend their property with armed force.

Pennsylvania Freeman Newspaper

Periodic outbreaks of racial, ethnic and religious violence were common in Philadelphia for nearly 15 years. Quaker Benjamin Lundy founded an abolitionist newspaper in 1836 which he named the National Enquirer. John Greenleaf Whittier renamed the paper the Pennsylvania Freeman after he took over as editor in 1838. Articles about “the riots” were still being published as late as 1844, as the following excerpts illustrate:

“Pennsylvania Hall,” Pennsylvania Freeman, n. 14. July 18, 1844.

The Civil War in Philadelphia.

This riotous and bloody city has just completed another terrible tragedy, which will probably beget another and another, till even ruffianism itself shall grow weary and sick of its dreadful deeds, and mobocracy be sated with human carnage. …Philadelphia has endeavored (and most successfully) to surpass all other places in murderous opposition to the cause of Negro emancipation. To propitiate southern slavemongers, and secure southern trade, she has treated abolitionists as outlaws, broken up their meetings by mobocratic assaults, burnt the dwellings and brutally maltreated the persons of many of her colored inhabitants, given Pennsylvania Hall to the consuming fire, &c. &c; and her reward has been, the loss of seventy million of dollars at the South, the blackning of her character with infamy throughout the civilized world, incendiary and bloody riots, and fiendish anarchy. Behold how awful, how just, and how swift has been the retribution of Heaven! Alleluia! For the Lord God omnipotent reigneth!! Truly, they who sow the wind, shall reap the whirlwind; and what shall be the end of these things!

This article published the same day in the Pennsylvania Freeman was entitled “The Riots”:

From the evidence taken by the Court of Common Please we are enabled to present a more accurate account of the principal features of the origin and progress of the late riots, than that which was given in the reports of the daily newspapers at the time. …

During the whole period of the history of the settlement of this continent by the whites, the law in more or less of the states, and in one feature or another, has recognized the right of one act of religious professors to lord it over the consciences of another set, to punish them for non-conformity, or to subject them to pecuniary tribute. Not only so, but we have constantly had a class of persons striving to extend the range of this religious tyranny and it is to the efforts of this class that the recent mobs are in a great measure attributable.

Though freedom of speech has been, in general, guaranteed by law, it has not been maintained in practice. For the last ten years the abolitionists have been subject to mob violence in three-fourths of the Union for the simple expression of their opinions. This violence has been either winked at, or indirectly approved, by a large portion of the men in authority, as well as of the political and religious leaders of the people.

Coming more directly to the city of Philadelphia, we find that about the year 1837 a few colored and white boys at a scene of amusement called the “flying horses,” got into a quarrel in which the white boys, who were probably the aggressors, were worsted. They sallied forth and collected a mob of men and boys with whom they made an indiscriminate assault on the colored people of Southwark and Moyamensing who had given them no provocation. They tore down some houses, ransacked others, destroyed furniture, beat women and children, and killed an inoffensive man who was too ill to escape by fight.

A large portion of the community sanctioned this horrible crime on the pretext that the colored people must be taught to know their places: the public authorities winked at it, and the rioters and murderers were never even brought to trial. …

Engraving by Granger

1839 Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women

The third Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women took place in the hall of the Pennsylvania Riding School in Philadelphia May 1 through May 3, 1839. The first day of the convention centered mostly about the immorality and inhumanity of the slave system. On May 2, Elizabeth L. B. Stickney offered the following resolution:

Whereas, Our principle, in regard to prejudice against color, remains unchanged by persecution, therefore,

Resolved, That we will continue to act in accordance with our profession that the moral and intelluctual character of persons, and not their complexion, should mark the sphere in which they are to move.

On Friday, May 3, Susan Grew submitted this resolution:

Resolved, That henceforward we will increase our efforts to improve the condition of our free colored population by giving them mechanical, literary, and religious instruction, and assisting to establish them in trades, and such other employments as are now denied them on account of their color.

Clarissa C. Lawrence seconded Grew’s motion and stated:

We meet the monster prejudice everywhere. We have not power to contend with it, we are so down-trodden. … We have been brought up in ignorance; our parents were ignorant, they could not teach us. We want light; we ask it, and it is denied us. Why are we thus treated? Prejudice is the cause. It kills thousands every day. … We are blamed for not filling useful places in society; but give us light, give us learning, and see then what places we can occupy. I bless God that the young are interested in this cause. It is worth coming all the way from Massachusetts to see what I have seen here.

The convention adjourned later in the day, and black and white women abolitionists began the long journey home.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Culture of Philadelphia

Gilder Lehrman Center: The Riots

Slavery in America: Pennsylvania Hall

Gilder Lehrman Center: Pennsylvania Hall

Wikipedia: Pennsylvania Hall (Philadelphia)

Angelina Grimke Weld’s Speech at Pennsylvania Hall

Wikipedia: Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women

Burning of Pennsylvania Hall in Anti-Abolitionist Riot of 1838

History Engine: The Significance of Rhetoric in Antebellum America

Am I Not A Woman and A Sister? The Anti-slavery Convention of American Women 1837-1839 – PDF