Civil War Diarists of Fredericksburg, Virginia

Fredericksburg, Virginia was occupied on three separate occasions by Union forces. These ‘invasions’ had an impact on the townspeople. The diaries of Fredericksburg residents allow us to experience their anxiety and fear toward enemy armies, as well as the loss of loved ones and the damage or destruction of homes and personal property.

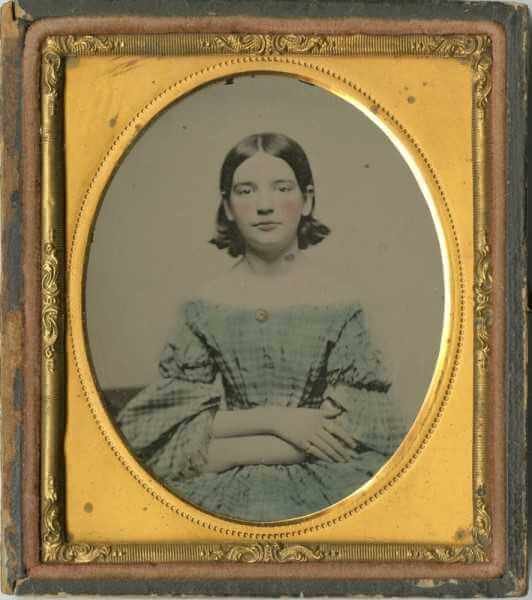

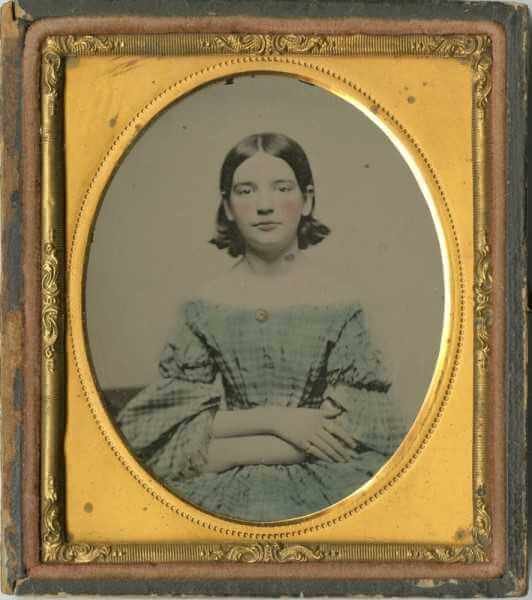

Elizabeth Maxwell Alsop

Elizabeth (Lizzie) Maxwell Alsop began writing her Civil War diary in 1862. She was the sixteen-year-old daughter of Sarah and Joseph Alsop, who lived at what is today 1201 Princess Anne Street in Fredericksburg, Virginia. Her father was one of the richest members of the Fredericksburg community; a large part of his wealth consisted of slaves.

The Alsops valued education for their daughters as much as for their sons. Lizzie and her sister Nannie attended boarding school – the Southern Female Institute in Richmond, Virginia – and spent part of the war there. Lizzie captured the heart of many a Confederate officer, but she did not return their affections.

On Tuesday, March 4, 1862, sixteen-year-old Lizzie Alsop began filling the blank pages of a new diary. Over the next seventy years, she completed nine such books. During her most intense period of writing from 1862 to 1866, she recorded the effects of the Civil War on her friends and family from both inside the Confederate capital and Union-occupied Fredericksburg.

She also recorded the emotional ups and downs of the Confederate States of America and her disdain for the Union soldiers who occupied her hometown in the spring of 1862. On May 23, she wrote:

We Confederates are, generally speaking, the most cheerful people imaginable, and treat the Yankees with silent contempt. They little know the hatred in our hearts towards them – the GREAT scorn we entertain for Yankees. I never hear or see a Federal riding down the street that I don’t wish his neck may be broken before he crosses the bridge.

Lizzie’s exposure to occupied Fredericksburg, as well as her time in the Confederate capital, allowed her to witness some of the most extraordinary events experienced by any region during the Civil War. The Alsops repeatedly found themselves in the direct path of one army or the other.

After the Union occupation of Fredericksburg in early December 1862, the Alsops decided to leave Fredericksburg. On December 29, 1862 Lizzie wrote:

Five weeks ago Father, Mother, Nannie [Lizzie’s sister], Mr. and Mrs. Allen fled from Fredericksburg, thought to be in imminent danger; and took refuge in this house [Hilton, their plantation home in the countryside of Spotsylvania County], and here they have been ever since and are likely to remain for some time. During the shelling of Fredericksburg, December 11th, 1862, very few citizens remained in town, not more than a hundred and fifty if so many. Uncle William and Mrs. Foulke were at our house, but after the Yankees crossed over they left.

The house [in Fredericksburg] was very much injured, every room rendered not inhabitable except two. … When any one asks Father how much they injured him he says I can tell you much better what they left, than what they destroyed. However we fared better than some.

Although the Confederate forces had won the Battle of Fredericksburg, Lizzie noted the following New Year’s Day that she had “been over the house and find destruction less than I had anticipated; true almost every room has a ball through it and the garden is much torn to pieces.” In her diary, Miss Alsop also expressed her everyday concerns over education, courtship, marriage, entertainment, and her frequently tumultuous relationship with her mother.

Lizzie’s family remained at Hilton plantation until the following summer, and on July 31, 1863 she noted:

Our last night at Hilton. Happy for the most part, has been our sojourn here, and with a sad heart I contemplate the woods, fields, and the little white house for the last time. Yet I most assuredly expect to see them again, but not in the same position as now.

After almost two more years of war, Lizzie recorded the surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee in April 1865:

I pray God, that I may yet live to see his vengeance exercised against our enemies; that I may live to see our brave, our noble army rise up from the ashes of our burning homes, and yet avenge the death of our heros slain. If they could chose, how few would come back to this life, for what is life compared with honour.

1201 Princess Anne Street

Fredericksburg VA

In September 1865, Lizzie wrote that she had become a Christian, remarking that, ‘by his grace I trust to lead a better life hereafter.’ However, she continued to struggle with the insecurities of the postwar South and the reduction of her family’s wealth and status.

Lizzie’s journal records her growth from adolescent to adult and the effect the Civil War had on a feminine ideal that emphasized beauty, gentleness, and submissiveness. She maintained her journal from 1862 through 1878, offering the opportunity to observe her growth from a teenaged Confederate patriot to a mature thirty-two-year-old woman on the eve of her wedding.

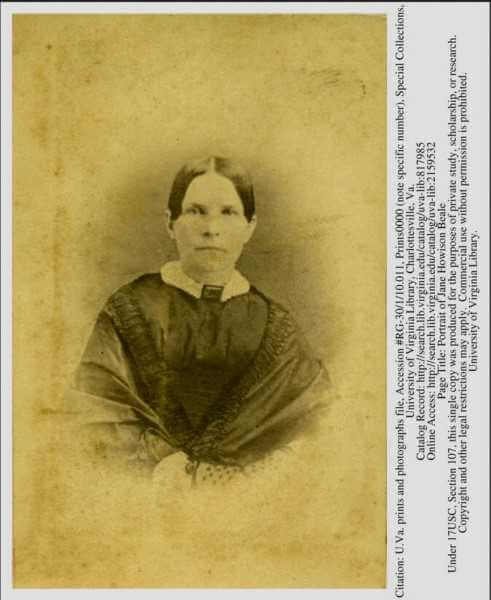

Jane Howison Beale

Jane Howison married William Churchill Beale in 1834, at the age of nineteen. In 1846, William purchased a beautiful brick home for them on Lewis Street in Fredericksburg, Virginia. After her husband died unexpectedly of a heart attack, leaving her with nine children to care for, Jane sold the mill they owned to pay off their debts. With the help of two of her daughters, she then opened a school for girls in a separate building behind the residence as a way to provide an income for her family.

The Union Army first occupied the town of Fredericksburg in the spring of 1862. On April 27, 1862, Jane Howison Beale wrote:

Fredericksburg is a captured town, the enemy took possession of the Stafford hills which command the town on Friday the 18th and their guns have frowned down upon us ever since, fortunately for us our troops were enabled to burn the bridges connecting our town with the Stafford shore and thus saved us the presence of the Northern soldiers in our midst, but our relief from this annoyance will not be long as they have brought boats to the wharf and will of course be enabled to cross at their pleasure, it is painfully humiliating to feel one’s self a captive, but all sorrow for self is now lost in the deeper feeling of anxiety for our army, for our cause, we have lost every thing, regained nothing, our army has fallen back before the superior forces of the enemy until but a small strip of our dear Old Dominion is left to us, our sons are all in the field and we who are now in the hands of the enemy cannot even hear from them [Union officials suspended mail delivery to and from the South]. Must their precious young lives be sacrificed, their homes made desolate, our cause be lost and all our rights be trampled under the foot of a vindictive foe …

Another element was added to Beale’s fears and anxieties about the war. Corporal Charles D. Beale was killed during heavy fighting near Williamsburg on May 5, 1862. Jane wrote in her diary on May 13, 1862:

Since my last entry my heart has been crushed with sorrow, for I have seen the death of my Son Charley mentioned in the Richmond paper. He fell in the battle near Williamsburg on Monday the 5th some time between the hours of 7 o’clock and 11 AM for it was then the battle waged. Sorrow has rolled in on my soul in heavy waves. … He was the best the most affectionate and dutiful of sons to his Mother and she will ever cherish his memory with a fondness which none other can know. Our heavenly Father has taken him in his early youth (just 20 years of age) before the shadow of the sinful world had fallen deeply upon him. …

Bombardment

After several months of relative calm, in late November 1862, Union troops arrived on the Stafford hills across the Rappahannock River from Fredericksburg, causing many white residents of the town to flee. Most took to the countryside, hoping to find shelter and sustenance at the farms of friends – or strangers if need be – in the countryside. Jane Howison Beale and her family remained at their home on Lewis Street.

On the morning of December 11, 1862, Union artillery began bombarding the town, warning of an impending battle. Beale later wrote, “before we were half dressed, the heavy guns of the enemy began to pour their shot and shell upon our ill-fated town, and we hastily gathered our remaining garments, and rushed into our Basement.”

Jane Howison Beale and her family spent the bombardment of Fredericksburg in the basement of their home. When a shell struck the house, a flying brick hit her youngest son, bruising him. Many hours later they escaped through the cellar door and fled town in an ambulance. Beale later recorded:

We were shoved into the vehicle without much ceremony, and the horses dashed off at a speed that at another time would have alarmed me, but now seemed all too slow for our feverish impatience to be beyond the reach of those terrible shots. One struck a building just as we passed it, another tore up the ground a short distance from us.

According to the historical record, during the Battle of Fredericksburg, Union soldiers destroyed or looted many homes. However, Beale’s house was spared. Many of the town’s enslaved people had already left, hoping to find protection and freedom in the Union lines, but some slaves remained in those houses during the battle.

Safely ensconced in the plantation home of friends at Beauclaire Plantation in Spotsylvania County, Jane Beale wrote on Monday, December 14, 1862:

We heard a few guns in the morning, but the firing ceased presently and we heard nothing more all that day and the next, but the moving of the wounded and burying of the dead. Various reports reached us, one of which was that General Lee intended destroying the town, thus driving the Yankees from their place of refuge. This came upon me with a great shock of distress, as I had just heard that my house was still standing. We afterwards heard that the presence of old and helpless females in the town prevented our noble, tender-hearted general from availing himself of this advantage.

The Battle of Fredericksburg stands as one of the greatest Confederate victories. Led by General Robert E. Lee, the Army of Northern Virginia routed the Union forces led by General Ambrose Burnside.

Jane Howison Beale lived on at 307 Lewis Street until her death in 1882.

SOURCES

Community at War: Lizzie Alsop

The mystery of Mary Caldwell’s ‘Aspen Cottage’

Fredericksburg Remembered: The Letters of Jane Beale

Fredericksburg Remembered: Schooling antebellum style