First American Feminists

Feminism in the United States is often divided chronologically into first-wave (1848-1920), second-wave (early 1960s to 1980s), and third-wave (1990s-present). As of the most recent Gender Gap Index measurement of countries by the World Economic Forum in 2014, the United States is ranked 20th in gender equality.

Bloomer and Stanton are wearing the Bloomer costume (shorter dresses).

Seneca Falls, New York

Anthony and Stanton: Always at the Forefront

In the spring of 1851, William Lloyd Garrison conducted an anti-slavery meeting in Seneca Falls. Susan B. Anthony attended, staying at the home of Amelia Bloomer. They met Elizabeth Cady Stanton on the street and immediately began their historic friendship.

The women had first met in 1851 when Anthony traveled to an antislavery meeting in Seneca Falls, New York when both women were in their thirties. Remembering the day Amelia Bloomer introduced them on a street corner, Stanton said:

There she stood with her good, earnest face and genial smile, dressed in gray delaine, hat and all the same color, relieved with pale blue ribbons, the perfection of neatness and sobriety. I liked her thoroughly, and why I did not at once invite her home with me to dinner, I do not know.

For much of the 1850s this pair agitated for economic freedoms for women, and then they fought the women’s battles of the last half of the nineteenth century. Anthony was an organizational and tactical genius. She displayed her skill by appearing before every Congress between 1869 and 1906 on behalf of women’s suffrage. Stanton was the thinker and writer. She worked for the women’s rights movement in all its phases while also raising seven children. Anthony often traveled from her home in Rochester, New York to help run the household while Stanton made magic with her pen.

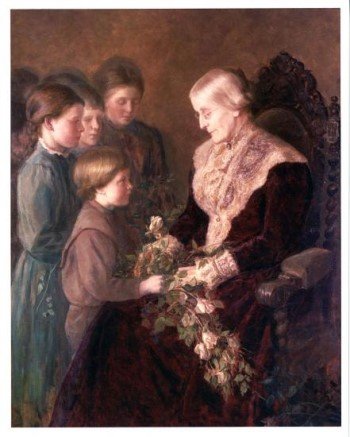

They had been an excellent team, but old age was creeping in. In 1902 Anthony wrote a letter to Stanton in honor of her eighty-seventh birthday:

It is fifty-one years since we first met, and we have been busy through every one of them, stirring up the world to recognize the rights of women. We little dreamed when we began this contest, optimistic with the hope and buoyancy of youth, that half a century later we would be compelled to leave the finish of the battle to another generation of women. But our hearts are filled with joy to know that they enter upon this task equipped with a college education, with business experience, with the fully admitted right to speak in public – all of which were denied to women fifty years ago. They have practically one point to gain – the suffrage; we had all.

And we, dear old friend, shall move on the next sphere of existence – higher and larger, we cannot fail to believe, and one where women will not be placed in an inferior position, but will be welcomed on a plane of perfect intellectual and spiritual equality.

First Wave of Feminists

It all began in 1840 when Elizabeth Cady Stanton met Lucretia Mott at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. The conference refused to seat Mott and other women delegates from America because of their gender. Stanton was the young bride of an antislavery agent and Mott, a Quaker preacher and veteran of reform movements. To pass the time, this unlikely pair walked the halls and discussed the need for a convention to address the rights of women.

However, daily life intervened – Stanton gave birth to three sons between 1842 and 1845 – and eight years passed before they took the next step, but this small step was a giant leap for womankind.

In the summer of 1848, Lucretia Mott was in western New York to attend a Quaker event, after which she visited her sister, Martha Wright, in Auburn, New York. On July 9, 1848 Mott met with Stanton and Mary Ann McClintock at the home of Jane Hunt in Waterloo. There they hurriedly planned a convention before Mott had to return home to Philadelphia.

The first wave of feminism in the United States began with the First Women’s Rights Convention. Held at the Wesleyan Chapel in Stanton’s hometown of Seneca Falls, New York on July 19 and 20, 1848, this was the first formal meeting organized to address gender inequality. More than three hundred women and men met there to discuss the current state of women’s legal rights and strategies to mobilize women across the country and foster serious change.

First Woman to Vote: Louisa Ann Swain

In 1869 Wyoming became the first territory or state in America to grant women suffrage. Louisa Ann Swain (1801-1880) rose early on September 6, 1870, put on her apron, shawl and bonnet, and walked downtown. The polling place had not yet officially opened, but election officials asked Swain to come in and vote. She was described by a Laramie newspaper as “a gentle white-haired housewife, Quakerish in appearance.” Swain was 69 years old when she cast the first ballot by any woman in the United States in a general election.

Image: Louisa Ann Swain

Life-sized bronze sculpture of the first woman to vote in the U.S.

Wyoming Women’s History House

Laramie, Wyoming

Today three flags fly from the front of the Wyoming Women’s History House, each of which has its significance in the life of Louisa Swain. The Virginia flag is for the state of her birth. The Maryland flag is for the state of her death. The Wyoming flag stands for the ballot she cast as the first woman to vote in the United States.

In 2008, September 6 was recognized by Congress as National Louisa Swain Day via House Concurrent Resolution 378:

Whereas September 6 would be an appropriate date to designate as Louisa Swain Day: Now, therefore, be it resolved by the House of Representatives (the Senate concurring), That Congress supports the designation of a Louisa Swain Day.

Separate Economy for Women

The Married Women’s Property Act passed in Maine in 1844 granted married women a ‘separate economy’ from their husbands; other states followed suit. This new freedom gave women the ability to earn their income and retain it for their use. Their husbands could no longer demand that she turn her money over to him to drink or gamble away.

Before the Civil War, women were primarily fighting for property and economic rights, as shown in this basic timeline:

1718

In Pennsylvania, women were able to own and manage property if their husbands were incapacitated.1771

New York became the first state to require a woman’s consent if her husband tried to sell property that she brought to a marriage. The act also required the judge to meet privately with the woman to reassure himself that the signature was not forged or her consent coerced.1839

Mississippi allowed women to own property in their own names – the first state to do so.1844

Married women in Maine became the first in the US to win the right to “separate economy.”1845

New York granted a married woman who secured “a patent for her own invention” the right to hold it and retain all earnings from it “as if unmarried.”1848

Married Woman’s Property Act was passed in New York which was later used as a model for other states, all of which passed their own versions by 1900. For the first time, a woman was not automatically liable for her husband’s debts; she could enter contracts on her own; she could collect rents or receive an inheritance in her own right; she could file a lawsuit on her own behalf. She became for economic purposes, an individual – for the first time.1862

The Homestead Act made it easier for single, widowed and divorced women to claim land in their own names.

In the same year, California passed a law that established a state savings and loan industry that also guaranteed that a woman who made deposits in her own name was entitled to keep control of the money. The state recognized the full financial independence of women – and in 1862 the San Francisco Savings Union approved a loan to a woman.

Ernestine Rose

Polish-born Ernestine Rose was one of the major intellectual forces behind the women’s rights movement in nineteenth-century America. In the winter of 1836, Judge Thomas Hertell submitted a resolution to the New York State Legislature, asking that body to investigate methods of improving the property rights of married women and to allow them to own real estate in their own name, not that of their husbands.

When Ernestine Rose heard of this resolution, she drew up a petition and began to solicit names in support of it. In 1838, she submitted the petition with the five signatures she had collected to the state legislature. Rose’s petition was the first ever introduced in favor of rights for women. During the following years, she increased both the number of petitions and the number of signatures.

As a part of a more general movement underway since the 1820s, the New York Married Women’s Property Act was enacted on April 7, 1848. The Act significantly changed the law governing the property rights granted to married women. For the first time women in the state of New York were allowed to own and control their own property. It was used as a model by several other states in the 1850s. The Act provided that:

• The real and personal property of any female who may hereafter marry, and which she shall own at the time of marriage, and the rents issues and profits thereof shall not be subject to the disposal of her husband, nor be liable for his debts, and shall continue her sole and separate property, as if she were a single female.

• The real and personal property, and the rents issues and profits thereof of any female now married shall not be subject to the disposal of her husband; but shall be her sole and separate property as if she were a single female except so far as the same may be liable for the debts of her husband heretofore contracted.

• It shall be lawful for any married female to receive, by gift, grant devise or bequest, from any person other than her husband and hold to her sole and separate use, as if she were a single female, real and personal property, and the rents, issues and profits thereof, and the same shall not be subject to the disposal of her husband, nor be liable for his debts.

• All contracts made between persons in contemplation of marriage shall remain in full force after such marriage takes place.

In the 1840s and 1850s, Ernestine Rose joined a group of great American women that included such influential figures as Anthony, Stanton, Paulina Wright Davis, and Sojourner Truth. However, Rose’s health began to fail, and on June 8, 1869, she and her husband set sail for England. Susan B. Anthony arranged a farewell party for the couple, at which they received gifts and a substantial amount of money from friends and admirers. She lived in England until her death in 1892.

Matilda Joslyn Gage

Gage was a women’s rights activist from Fayetteville, New York who attended the Third National Woman’s Rights Convention in Syracuse, New York in September 1852 and made her first public speech there. Gage was a member of Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s National Woman Suffrage Association, founded in 1869, and a contributor to its newspaper, The Revolution. She helped establish the New York State Woman Suffrage Association in 1869 and served as its vice president and secretary.

Matilda Joslyn Gage was never entirely comfortable on the speaker’s platform, bu she was an effective advocate with her pen. With Stanton and Anthony she drafted the “Declaration of Rights for Women” that was presented on the Fourth of July at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876. She coauthored with Stanton and Anthony the first three volumes of History of Woman Suffrage, a history of the women’s suffrage movement that was published in six volumes from 1881 to 1922.

Gage’s lifelong motto appears on her gravestone in the Fayetteville Cemetery

There is a word sweeter than Mother, Home or Heaven; that word is Liberty.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Ernestine Rose

Wikipedia: Louisa Ann Swain

Wikipedia: First-Wave Feminism

Wikipedia: Feminism in the United States

Wikipedia: Married Women’s Property Acts in the United States

The Guardian: Women’s rights and their money: a timeline from Cleopatra to Lilly Ledbetter

Humanities: Old Friends Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony Made History Together