Abolitionist, Suffragist and Philanthropist

Elizabeth Buffum Chace was a tireless life-long activist in the Anti-Slavery, Women’s Rights, and Prison Reform movements of the mid-to-late 19th century. Following in the footsteps of her father, the first president of the New England Anti-Slavery Society, Chace helped found the Fall River Female Anti-Slavery Society in 1835.

Early Years

She was born Elizabeth Buffum in Smithfield, Rhode Island on December 9, 1806 to Arnold Buffum and Rebecca Gould Buffum, whose families were among the oldest in New England. Elizabeth grew up in a household of anti-slavery Quakers and she spent a year studying at the Friends’ Boarding School in Providence in 1822.

Elizabeth later recalled her father softly singing William Cowper’s Abhorrence of Slavery as he went about his daily activities around the house:

I would not have a slave to till my ground,

To carry me, to fan me while I sleep,

And tremble when I wake, for all the gold

That sinews bought and sold have ever earned.

No ; dear as freedom is, and, in my heart’s

Just estimation, prized above all price,

I would much rather be myself the slave,

And wear the bonds, than fasten them on him;

Marriage and Family

Her family then moved to Fall River, Massachusetts, where she met and married fellow Quaker Samuel Buffington Chace on April 4, 1828. Samuel was a textile manufacturer who owned several mills in New England. Elizabeth’s first five children died of various diseases between the ages of 2 and 9; three died of scarlet fever. She gave birth to her sixth child and four more followed; the youngest was born in 1852 when Elizabeth was 45 years old.

Anti-Slavery Movement

Chace’s family were dedicated abolitionists while she was growing up but after her marriage to manufacturer Samuel Chace of Fall River, Massachusetts she became a radical antislavery activist. Samuel, although not as outspoken as his wife, shared her beliefs, and they opened their home in Fall River as a Station on the Underground Railroad and helped runaway slaves on their way to Canada.

The family moved to Valley Falls, Rhode Island in 1839 when Samuel took over management of the Valley Falls Mills on the Blackstone River. There they established their home as the main stop on the Underground Railroad in Rhode Island. In the 1840s, there were numerous struggles over slavery within the Society of Friends, as Elizabeth Buffum Chace recalled:

Several persons, in various parts of the country, were forcibly carried out of the Friends meeting for attempting therein to urge upon Friends the duty to maintain, faithfully their testimony against slavery, as their Discipline required. A few meeting houses in country places, had been opened for the Anti-Slavery meetings, whereupon our New England Yearly Meeting adopted a rule that no meeting house under its jurisdiction should be opened except for meetings of our religious Society.

Elizabeth Chace entered public life as a member of the Garrisonian antislavery movement established by William Lloyd Garrison in the 1830s. The Garrisonians, a small group of abolitionists, were the most uncompromising antislavery activists in calling for the immediate emancipation of slaves and were considered dangerous radicals who threatened the social order.

Female antislavery activists like Chace urged northern women to take to the streets on behalf of slave mothers and their children. They encouraged mothers to train their children to be activists, and they fervently believed in the power of women to accomplish social change. The concept of home as a haven where children were protected educated and nourished, was paramount.

In her work Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, which she wrote at the age of eighty-five, Chace wrote about her Underground Railroad activities:

Slaves in Virginia, would secure passage, either secretly or with con sent of the Captains, in small trading vessels, at Norfolk or Portsmouth, and thus be brought into some port in New England, where their fate de pended on the circumstances into which they hap pened to fall. A few, landing in some town on Cape Cod, would reach New Bedford, and thence be sent by an abolitionist there to Fall River, to be sheltered by Nathaniel B. Borden and his wife, who was my sister Sarah, and sent by them, to Valley Falls, in the darkness of night, and in a closed carriage, with Robert Adams, a most faithful friend, as their conductor.

Here, we received them, and, after preparing them for the journey, my husband would accompany them a short distance, on the Providence and Worcester railroad, acquaint the conductor with the facts, enlist his interest in their behalf, and then leave them in his care, to be transferred at Worcester, to the Vermont road, from which, by a previous general arrangement, they were received by a Unitarian clergyman named Young, and sent by him to Canada, where they uniformly arrived safely.

I used to give them an envelope, directed to us, to be mailed in Toronto, which, when it reached us, was sufficient by its post-mark, to announce their safe arrival, beyond the baleful influence of the Stars and Stripes, and the anti-protection of the fugitive slave law.

As a result of her antislavery work, Chace became a social outcast, but she found comfort in a small circle of radical abolitionists like herself. In 1858 she moved to a spacious home in what is now Central Falls, Rhode Island and hosted anti-slavery speakers like Frederick Douglass, Wendell Phillips, and Sojourner Truth. With the ou Civil War in 1861, the Samuel and Elizabeth firmly supported the Union cause, but they were disappointed that President Abraham Lincoln did not immediately abolish slavery.

Women’s Rights Movement

After the Civil War, Elizabeth Buffum Chace worked to secure political rights for women, supporting young women who were denied a college education because of their gender and numerous other reforms.

In her letters to newspaper editors, her appearances at legislative hearings, and her organization of protests and conventions, she was the most prominent woman reformer in nineteenth century Rhode Island.

Chace was a founder and board member of women’s organizations like the Association for the Advancement of Women and co-founder of the Rhode Island Woman Suffrage Association, for which she served as president from 1870 until her death. Chace was the driving force behind a women’s suffrage amendment that was rejected by Rhode Island voters in 1887, and was also influential in the founding of Pembroke, the women’s college associated with Brown University.

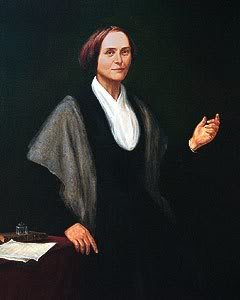

Image: Elizabeth Buffum Chace

With unidentified child

From Portraits of American Abolitionists

Massachusetts Historical Society

State Home and School for Children

Chace’s grief following the deaths of her children was formative; it impelled her, in 1843, to reject the Quakerism in which she had been bred and married, and to embrace the extreme and unpopular radical Garrisonian activism as her religion. She converted the helplessness she felt at the bedsides of her own dying children into activism on behalf of other suffering children who could be helped.

Elizabeth Buffum Chace’s solution to caring for indigent children in Rhode Island was to create an institution where children would be nurtured and educated by kind, loving adults, where children would receive training in a trade or profession according to their abilities and interests. “Homelessness is not a crime,” she asserted in a newspaper article advocating for her vision of the school.

She abhorred the Reform School system where girls were trained only in housework:

No girl should be kept peeling potatoes or washing dishes who has the making of a good bookkeeper or fine wood carver or engraver; no boy should spend his minority in cane-seating chairs if he has a genius for architecture or any higher mechanical labor.

There should be a large, plain central building, in which should be kitchen, laundry, dining-room, school-rooms, workship, hall and sleeping rooms for adult persons employed therein. Then … a circle of cottages around the central house, all facing toward it … In each cottage I would place a good woman and a certain number of children; and this should be their home when not engaged at school, or meals or work. … Each household of children should be under the care of the matron of its own cottage, who should, as nearly as possible, supply the place of a mother to them.

The whole establishment should be under the general care of a superintendent and head matron, who should also live in a cottage in the circle, in order to have the whole institution under their eyes.

Unfortunately, Chace’s plans for the State Home and School for Children were far from realized. She was just short of eighty years old and in failing health when the School was built in 1885, and her attention turned the following year to a statewide referendum for woman suffrage, which she directed from her bedroom, where she was confined by illness.

Despite her failing health, Chace visited the school several times a year after it opened, “made some inspection of the buildings, and talked with the officers [officials] and children.” She was unaware of problems at the school, including lack of food and corporal punishment. In 1889, a worker informed Chace that children were being mistreated there. Chace’s daughter later wrote:

The shock and the horror that the old woman felt can only be imagined. But she bestirred herself at once, and one of the Providence papers said that the mere fact that Mrs. Chace believed there was something wrong in the State School was sufficient reason why an investigation should be made. She girded herself up for what was to be her last great personal conflict with official authorities, but it was difficult, at first, to obtain an investigation into allegations of misdeeds at the newly opened school.

Unfortunately, Elizabeth Buffum Chace was too far advanced in age to continually tackle the problems that always accompany the establishment of an institution as the State Home and School for Children. She died December 12, 1899 at the age of 93.

Conscience of Rhode Island

In 2001, Rhode Island Secretary of State, Edward S. Inman III selected Elizabeth Buffum Chace to be honored with a bronze bust in the Rhode Island State House as The Conscience of Rhode Island for her tireless championing of the rights of the less fortunate.

Inman chose Chace out of a field of thirty-six nominees including Anne Hutchinson and Christiana Carteaux Bannister.

In her incisive letters to the editor, her appearances at legislative hearings, her organization of protests and conventions, she was the most prominent woman reformer in nineteenth century Rhode Island. She is a founder and board member of national women’s organizations, like the prestigious think tank the Association for the Advancement of Women and the American Woman Suffrage Association. Elizabeth Buffum Chace was called the Conscience of Rhode Island.

Image: Bust of Elizabeth Buffum Chace

The Conscience of Rhode Island

Influential Children and Grandchildren

The Chace children and grandchildren played large roles in higher education in the 20th century. Elizabeth’s son, Arnold Buffum Chace, became the Chancellor of Brown University and a renowned mathematician associated with the Rhind Papyrus, the best example of Egyptian mathematics. Daughter Lillie Chace Wyman became a tireless social reformer and an author, publishing several books and writing regularly for such magazines as The Atlantic Monthly.

Two of Chace’s grandsons, Richard Chace Tolman and Edward Chace Tolman both became well-known professors. Richard played a crucial role as Scientific Liaison for the United States Army on the Manhattan Project, which produced the first nuclear weapons during World War II. Edward, a pioneer in Behaviorism, a systematic approach to the understanding of human and animal behavior which assumes that the behavior of a human or an animal is a consequence of that individual’s history. He successfully sued the University of California, Berkley for firing him for refusing to sign the infamous Loyalty Oath during the McCarthy Era in the 1950s.

SOURCES

Anti-slavery Reminiscences

Wikipedia: Elizabeth Buffum Chace

Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Conductor on the Underground Railroad

Elizabeth Buffum Chace and Creation of the State Home and School for Children (Homelessness Is Not A Crime: Elizabeth Buffum Chace and Creation of The State Home and School for Children, 1875-1885)