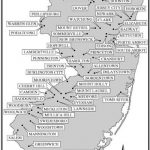

Safe House for Authors and Fugitive Slaves

The Wayside, a residence in Concord, Massachusetts, served as a safe house for fugitive slaves seeking freedom on the Underground Railroad in the mid-nineteenth century. It was also home to three American literary figures: Louisa May Alcott, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Margaret Sidney.

Image: The Wayside

Underground Railroad at The Wayside

The Wayside is located on the same road upon which the British advanced and retreated on April 19, 1775 when the colonists began fighting for their liberty from Britain. One of the early occupants, Samuel Whitney, was a muster master for the Concord Minutemen. Whitney had fought bravely for American independence, but he also owned slaves, who yearned for liberty as much as their master. Henry David Thoreau wrote that one of Whitney’s slaves fled from the house and volunteered as a soldier in the Revolutionary War, thereby earning his freedom at the end of the war.

In 1783, the state of Massachusetts abolished slavery. However, the 1793 Fugitive Slave Act, a federal law, required that escapees be returned to their owners and punished residents who harbored them.

What we now call the Underground Railroad (UGRR) developed over time into a system of stations along several routes from the South to Canada or the free states – states that had abolished slavery within their borders.

The Alcotts at The Wayside

Louisa May Alcott, author of Little Women, lived here with her parents, Bronson and Abigail May Alcott, and her three sisters during her early teenage years, from April 1845 to November 1848. Her father founded an abolitionist society in 1830 and became a member of the Boston Vigilance Committee in 1850. During their stay at The Wayside, it served as a station on the Underground Railroad. Louisa and her family knew the risks of helping runaway slaves but still dedicated themselves to the effort.

In his journal, Bronson Alcott described his family’s reaction to one of the fugitives they protected:

He has many of the elements of a hero. His stay with us has given image and a name to the dire entity of slavery, and was an impressive lesson to my children, bringing before them the wrongs of the black man and his tale of woes.

Bronson’s wife, Abigail, was no less committed. She joined other notable Concord women in the abolitionist movement, such as Henry David Thoreau’s sister Helen and Lydian Emerson, wife of Ralph Waldo Emerson.

These two excerpts from Underground Railroad in Concord and at The Wayside prove that the Alcotts aided fugitive slaves on their way to freedom in Canada.

From a letter Mrs. Alcott wrote to her brother January 13, 1847:

We have had an interesting fugitive here for 2 weeks – right from Maryland. He was anxious to get to Canada and we have forwarded him the best way we could. His sufferings have been great, his intrepidity unparalleled. He agrees with us about Slave produce [not purchasing products produced by slaves]; he says it is the only way the Abolition of the Slave can ever be effected. He says it will never be done by insurrection…

From Bronson Alcott’s journal entry of February 9, 1847:

Our friend the fugitive, who has shared now a week’s hospitalities with us, sawing and piling my wood, feels this new taste of freedom yet unsafe here in New England, and so has left us for Canada. We supplied him with the means of journeying, and bade him a good God speed to a freer land. He is scarce thirty years of age, athletic, dextrous, sagacious, and self-reliant. He has many of the elements of the hero. His stay with us has given image and a name to the dire entity of slavery, and was an impressive lesson to my children, bringing before them the wrongs [done to] the black man and his tale of woes.

The Alcotts apparently continued aid fugitives while living in Boston. Abigail discussed her activities in a February 28, 1851 letter to her brother Samuel May:

I have sent 20 colored women to service in the country, where for the present they will be safe. [I] may yet meet the penalties of the law [Fugitive Slave Law of 1850] – I am ready.

Looking back at her family’s involvement in the anti-slavery movement, Louisa May Alcott wrote in 1881 that she was prouder of their endeavors than of all the books she wrote.

Image: Louisa May Alcott

Underground Railroad in Concord

The town of Concord reflected the divisions in the country. Most residents of Concord were against slavery but opinion differed on the support of the abolitionist movement. Many citizens believed abolitionists were too extreme; some supported a gradual approach to ending slavery. While all abolitionists were against slavery, some were not active in the Underground Railroad.

Mary Merrick Brooks, wife of lawyer Nathan Brooks, was president of the Concord Women’s Antislavery Society which was organized in the 1830s and consisted of about seventy members. She was also an associate and friend of well-known abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips.

The Society planned functions, such as fairs, that raised money to assist in the antislavery effort. Brooks sold what she called Brooks cakes from her own recipe to her friends and neighbors to raise funds to provide food, clothing and train tickets for fugitives.

Brooks has been described as “probably Concord’s leading woman abolitionist,” and she was also very active in the UGRR there. She had influence with the male leaders of the town and was capable of mobilizing others to collect money and participate in other abolitionist activities.

Dr. Josiah Bartlett, who served Concord as a physician from 1820 to 1877, drove fugitives in his carriage to the next station on the Underground Railroad.

Underground Railroad at Walden Pond

Another of Concord’s resident authors, Henry David Thoreau was an ardent and outspoken abolitionist who served as a conductor on the UGRR. For two years, from July 1845 to September 1847, he lived in a cabin he built on the northern shore of Walden Pond, which was really a lake. He lived a simple life in natural surroundings without support of any kind:

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practice resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness to the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give a true account of it in my next excursion.

Thoreau sheltered fugitives during the day at Walden Pond and brought them to safe houses in Concord at night. He includes among his visitors runaway slaves who sometimes stopped and listened as if they heard hounds on their trail.

Underground Railroad at the Thoreau House

After his experiment in frugal living, Henry returned to live at the Thoreau family home in Concord. His mother Cynthia Thoreau founded the Concord Abolitionist Committee and became the town’s most active stationmaster on the Underground Railroad.

Image: The Wayside, Home of the Authors

Beginning in the early 19th century, New England suffered an epidemic of tuberculosis, or consumption, for decades. Victims suffered from hacking, bloody coughs, debilitating pain in their lungs, and fatigue. When people with tuberculosis coughed, sneezed, sang, or even talked, the germs may be spread into the air. If others inhaled these germs, they might become infected. At that time, however, no one knew how it spread or how to treat it.

The Thoreau family was hit particularly hard by the disease. Cynthia Dunbar Thoreau (1787–1872) and her husband John Thoreau (1787–1859) had been blessed with four children: Helen (1812-1849), John Jr. (1814-1842), Henry David (1817-1862), and Sophia (1819-1876). Except for John Jr., who died of tetanus, Cynthia lost all of her children to tuberculosis.

The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 required local authorities and all citizens to assist in the capture of a runaway slave. The punishment for preventing the arrest of a fugitive or by hiding an escapee was a fine of one thousand dollars and imprisonment for up to six months. The new law created great fear among African Americans who had escaped from slavery years earlier and were then living in the North. Many moved to Canada after the Law went into effect.

Nevertheless, Cynthia Thoreau continued to hide runaway slaves in her home, in direct defiance of the law that could have sent her to prison. At times Henry purchased train tickets for fugitives and escorted them to the West Fitchburg railroad station nearby. He often rode the same train to be sure the traveler was safely on his way. Thoreau sat separately from the slave so as not to arouse suspicion.

The Fitchburg Railroad opened its route through Concord in 1844, with connections north to Vermont and Canada. The Concord Depot facilitated the efforts of residents to aid the escape of fugitive slaves to freedom. On October 1, 1851 Thoreau wrote in his journal that a fugitive named Henry Williams stayed at the Thoreau home until money could be gathered to purchase his train fare.

Thoreau caught a cold in late 1860, which aggravated the tuberculosis he had contracted during his college days. He lived his last months in Concord editing his manuscripts before dying on May 6, 1862, at the age of forty-four. He was buried at the Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord.

Because secrecy was important for the operation of the UGRR, both for the fugitive and the people who helped them, it is not possible to know how many people in Concord were active in the UGRR and how many fugitives were helped.

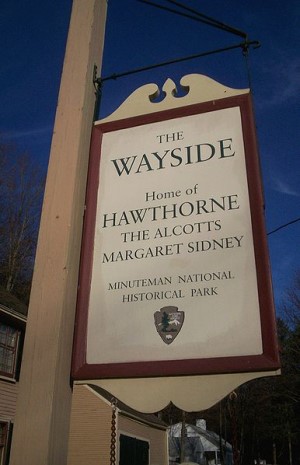

The Hawthornes at The Wayside

In 1852 the Alcotts sold The Wayside to Nathaniel and Sophia Hawthorne for $1,500. On March 8, 1852, they moved in with their three young children: Una, Julian and Rose. Hawthorne, author of The Scarlet Letter, lived here from 1852 until his death in 1864; it was the only home Hawthorne ever owned and the place where he wrote his last works.

Image: Nathaniel Hawthorne

The family lived in England while Nathaniel served as United States consul at Liverpool (1853-1857), and they remained in Europe until 1860. During that time, they leased The Wayside to family members including Sophia’s sister, Mary Peabody Mann.

When the Hawthornes returned to the United States, they soon realized that they had outgrown The Wayside and needed to expand their living area. Nathaniel wrote of their financial situation: “with a wing of a house to build, and my girls to educate, and Julian to send to Cambridge [to study at Harvard College].”

The family settled in and made changes to the home, including a three-story tower on the back of the house. The top room became Nathaniel’s study, which he named his sky parlor. They also added a second story over the west wing and enclosed the bay porch. Nathaniel was not entirely pleased with the result:

I have been equally unsuccessful in my architectural projects; and have transformed a simple and small old farmhouse into the absurdest anomaly you ever saw; but I really was not so much to blame here as the village carpenter, who took the matter into his own hands, and produced an unimaginable sort of thing instead of what I asked for.

The family lived here until Nathaniel’s death in 1864. Sophia and her three children moved to England shortly after; she sold The Wayside in 1870. George Parsons Lathrop, an author and husband of Hawthorne’s daughter Rose, purchased the house in 1879.

Boston publisher Daniel Lothrop and his wife Harriett bought The Wayside in 1883 after slavery had been abolished. Harriett wrote The Five Little Peppers and How They Grew and other children’s books under the pseudonym Margaret Sidney. The Lothrops added town water service in 1883, a large veranda on the west side in 1887, central heating in 1888, and electricity and lighting in 1904.

Image: Margaret Sidney

The Wayside was the first site of literary importance acquired by the National Park Service and is now open to the public as part of Minute Man National Historical Park. The house is also designated as a recognized stop on the Underground Railroad by the National Park Service. The Wayside barn, now a visitors’ center, was used by the Alcott girls to stage the plays that were created while they lived there.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: The Wayside

NPS.gov: The Wayside (Author’s Home)

Underground Railroad in Concord and at The Wayside – PDF

New Boston Post: Underground Railroad History at Concord’s Wayside