Wives Fought to Keep Families Together

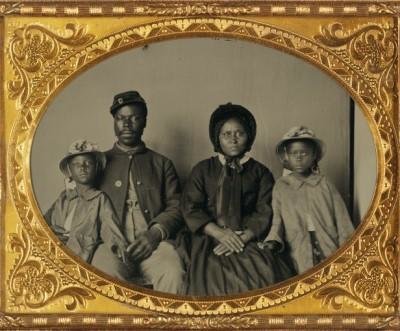

Image: Unidentified African American soldier in Union Uniform with his wife in dress and hat and two daughters in matching coats and hats.

Image: Unidentified African American soldier in Union Uniform with his wife in dress and hat and two daughters in matching coats and hats.

As the news of the attack on Fort Sumter spread, free black men hurried to enlist in the Union Army, but a 1792 Federal law barred African Americans from bearing arms for the United States. However, by the summer of 1862 the escalating number of former slaves and the pressing need of men to fill the ranks for the Union Army caused the government to reconsider.

Backstory

African Americans have volunteered to serve their country in time of war since the American Revolution. The National Archives and Record Administration (NARA) in Washington DC holds military service records. According to those documents, approximately 185,000 men served with the United States Colored Troops (USCT) during the Civil War. This figure includes the officers who were white.

In 1861 at Fort Monroe in Virginia, a few slaves escaped to the lines of USA General Benjamin Butler. The Confederate colonel who owned the slaves demanded that his slaves be returned to him under the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. Butler informed him that since Virginia had left the Union, the Fugitive Slave Law no longer applied to him. Butler kept the runaway slaves and declared them contraband of war; this was made the policy throughout the Union Army.

Letters from Home

Many wives of black recruits were not accustomed to having their husbands away from them for so long. Letters from wives in military service records detail the suffering war brought – illness, hardship, and lack of funds. Letty Barnes wrote this letter to her husband Joshua of the Thirty-eighth USCI (United States Colored Infantry):

My dear husband

I have just this evening received your letter sent me by Fredrick Finich. You can imagine how anxious and worry I had become about you. And so it seems that all can get home once in awhile to see and attend to their familey but you. I do really think it looks hard. Your poor old Mother is hear delving and working like a dog to try to keep soul and body together and here am I with two little children and myself to support and not one soul or one dollar to help us. I do think if your officers could see us they would certainly let you come home and bring us a little money.I have sent you a little keepsake in this letter which you must prize for my sake. It is a set of Shirt Bossom Buttons whenever you look at them think of me and know that I am always looking and wishing for you. Write to me as soon as you receive this. Let me know how you like them and when you are coming home and believe me as ever,

Your devoted wife,

Letty Barnes

Of course, African American men in the Union Army also worried about their families on the home front. Absolom Harrison wrote this letter to his wife January 19, 1862:

Camp Morton

Near Bardstown, Nelson County, KentuckyDear Wife,

I take my pen in hand to write you a few lines. I am tolerable well at present and I hope these few lines may find you and the children and all the rest of the folks well. I started to write to you the other day but I had only time to write a few lines. I had to expedition and I had been out two days so I concluded to write again. There is a good many of our men sick and there will be a good sick yet for we have been laying on the wet ground ever since we have been here without any straw under us. And the water runs under us every time it rains. …[Our camp] was very nice in a woods pasture place when we first came here. But it is knee deep in mud now. You must write as soon as you get this if you have not already wrote. I would like to know how mother is and how you and the children are and if folks are getting along.

I would like to be at home but I have got myself in this scrape and I will have to stand it. But if I live to get out of this I will never be caught soldiering again that is certain. We did not know what hard times was until we come to this place. We don’t get more than half enough to eat and our horses are not half fed and everything goes wrong.

So nothing more at present but remaining your affectionate husband until death.

A. A. Harrison

Second Confiscation and Militia Act

The Second Confiscation and Militia Act of July 17, 1862 officially authorized the employment of African Americans in federal service, and allowed President Abraham Lincoln to use persons of African descent for any purpose “he may judge best for the public welfare.”

Military officials raised three Union regiments of African Americans in New Orleans, Louisiana in the fall of 1862. These units were originally named the First, Second, and Third Louisiana Native Guard, but they later became the First, Second, and Third Infantry, Corps d’Afrique, and they were finally designated the Seventy-third, Seventy-fourth, and Seventy-fifth United States Colored Infantry (USCI).

However, the President waited until after he issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863 to authorize the use of African Americans in combat:

And I further declare and make known, that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.

Recruiters officially organized the First South Carolina Infantry (African Descent) in January 1863; they would become the Thirty-third USCI. The First Kansas Colored Infantry was mustered into service in January 1863, later the Seventy-Ninth USCI. These early unofficial regiments received little federal support, but they illustrated the black men’s desire to fight for freedom.

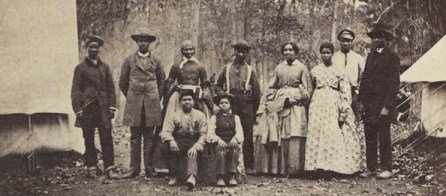

Image: 33rd U.S. South Carolina Regiment

Image: 33rd U.S. South Carolina Regiment

Colored regiment in their famous red pants

To speed up the process of recruiting more regiments, Union officials sent General Lorenzo Thomas to the lower Mississippi Valley in March. Thomas was ordered to enlist volunteers and white officers to command them, and he was successful in this endeavor. Stanton did authorize African Americans to serve as surgeons and chaplains, and by the end of the war, there were at least eighty-seven black officers in the Union army. In late January 1863, they gave Governor John Andrew of Massachusetts permission to raise a regiment of African American soldiers, the first black regiment organized in the North.

Bureau of Colored Troops

In May 1863, Union Secretary of War Edwin Stanton issued General Order Number 143, creating the Bureau of Colored Troops, which was authorized to organize and coordinate regiments throughout the nation. The designation United States Colored Troops (USCT) replaced the names of various state titles previously given to African American soldiers, but a few retained their state names, like the Corps d’Afrique in the Department of the Gulf.

The NARA created the Civil War Conservation Corps (CWCC), a volunteer project with private citizens who compiled military service records for each USCT volunteer. The CWCC project revealed fascinating stories about the soldiers of the USCT. Samuel Cabble, a private in the Fifty-fifth Massachusetts Infantry (Colored), was a twenty-one-year-old slave when he joined the army. The following letter is in his file:

Dear Wife:

I have enlisted in the army. I am now in the state of Massachusetts but before this letter reaches you I will be in North Carolina, and though great is the present national difficulties yet I look forward to a brighter day when I shall have the opportunity of seeing you in the full enjoyment of fredom. I would like to know if you are still in slavery; if you are it will not be long before we shall have crushed the system that now opresses you. For in the course of three months you shall have your liberty. Great is the outpouring of the colored people that is now rallying with the hearts of lions against that very curse that has separated you and me, yet we shall meet again. And oh what a happy time that will be when this ungodly rebellion shall be put down and the curses of our land is trampled under our feet. I am a soldier now and I shall use my utmost endeavor to strike at the rebellion and the heart of this system that so long has kept us in chains.

I remain your own afectionate husband until death.

Samuel Cabble

Among the documents in Cabble’s file is an application for compensation signed by his former owner, which would have been used as proof that his owner had offered Samuel for enlistment.

On October 3, 1863, the Union War Department issued General Order No. 329 to facilitate recruiting in the states of Maryland, Missouri, Tennessee, and Kentucky. Section 6 of that order states that any citizen offering his or her slave for enlistment into the military service would:

… if such slave be accepted, receive from the recruiting officer a certificate thereof, and become entitled to compensation for the service or labor of said slave, not exceeding the sum of three hundred dollars, upon filing a valid deed of manumission and of release, and making satisfactory proof of title.

Every owner was required to produce a title showing they owned the slave and to sign an oath of allegiance to the United States government.

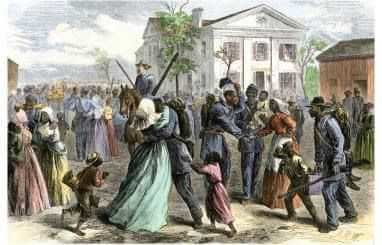

Image: Colorized image of black soldiers greeted by wives after being mustered out of service.

Image: Colorized image of black soldiers greeted by wives after being mustered out of service.

Harper’s Weekly, May 19, 1866

At the war’s end, most of the African American regiments were mustered out and sent home. Here the troops of the 54th USCI (United States Colored Infantry) greet their wives and children upon their discharge at Little Rock, Arkansas.

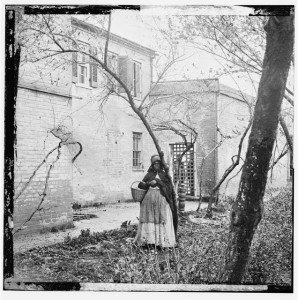

Camp Nelson Expulsion

African American soldiers enlisted and trained at Camp Nelson, Kentucky. Most of these recruits were runaways who had left without their masters’ permission, and they knew their families would be “subjected to the hands of their indignant masters.” Therefore, wives routinely accompanied the men, hoping to find food, shelter and the opportunity to earn a living as cooks and laundresses in the camp.

Army officials were troubled by the presence of these refugees, and in July 1864, they ordered camp commanders to dismiss all African American dependents. Once removed, these families set up some type of shelter outside the camp and still sought support and protection from the Union army, but they quickly realized they had been abandoned.

For several months, Army leadership ordered troops to expel these refugees from the camp, but newcomers were continually arriving and those who had been previously dismissed often returned. The families were continually harassed until camp officials finally “turned four hundred women and children from their dwellings to face the wintry blast, with light and tattered garments, no food, and no home!”

After the “helpless women and sick children” were removed, armed soldiers demolished their dilapidated dwellings on the perimeter. But the problem lingered until late November when Camp Nelson commander General Speed Fry expelled all refugees and destroyed the makeshift homes they had erected outside the Camp to prevent their return. Amid the turmoil, hundreds of refugees died of disease or exposure to the elements.

A black recruit named Joseph Miller brought his wife and four children with him when he came to enlist, assuming his master would mistreat them on the plantation once they discovered he was missing. They were assigned to a tent inside Camp Nelson, but a few days later they were removed from the fort. Later that night, Miller discovered that his family were six miles away, thrown together with many others in an old meeting house. Miller returned to duty at the camp that night but returned the following day to bury his son who had died from exposure to inclement weather.

In the November 28, 1864 issue of the New York Tribune published an article entitled “The Cruel Treatment of the Wives and Children of U.S. Colored Solders”:

Over four hundred helpless human beings – frail women and delicate children – having been driven from their homes by United States soldiers, are now lying in barns and mule sheds, wandering through woods, languishing on the highway and literally starving, for no other crime than their husbands and fathers having thrown aside the manacles of slavery to shoulder Union muskets. The deluded creatures innocently supposed that freedom was better than bondage and were presumptuous enough to believe that the plighted protection of the Government would be preserved inviolate.

The northern press and the U.S. Sanitary Commission severely criticized General Fry. Washington officials directed Fry to establish a camp for the refugees within Camp Nelson. In March 1865, a congressional act passed which freed the wives and children of these African American soldiers, a direct result of the November 1864 expulsion of refugees at Camp Nelson.

By June 1865, there were ninety-seven cottages in the refugee camp and numerous tents and shacks, which provided housing for more than three thousand refugees, primarily women and children. Several other buildings were erected in the camp, including a school house, a hospital, a mess hall, a laundry, a lime kiln, teacher’s quarters and offices.

By the end of the Civil War in April 1865, the one-hundred seventy-five USCT regiments made up approximately one-tenth of the Union Army. Approximately ten thousand soldiers from the United States Colored Troops were killed or mortally wounded during the war; an astounding thirty thousand more died of infection or disease.

Thousands of African American women served as nurses, spies, cooks, laundresses and performed countless other jobs in support of the men on the front lines.

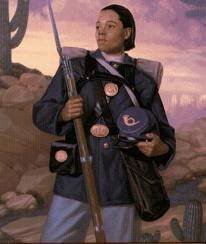

After the War, some USCT soldiers moved west and fought in the Indian Wars. Native Americans thought their hair looked the fur of bison and named them Buffalo Soldiers. On July 24, 1870, Emanuel Stance – former sharecropper, now United States Army sergeant – was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for Valor for his bravery in the Battle of Kickapoo Springs, Texas. He was the first African American to receive the highest military honor after the Civil War.

Image: African American Civil War Memorial

Image: African American Civil War Memorial

This monument, The Spirit of Freedom, is a nine-foot bronze statue by Ed Hamilton of Louisville, Kentucky, commissioned by the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities in 1993. The memorial includes curved panels inscribed with the names of the men who served in the USCT during the war.

The African American Civil War Memorial Freedom Foundation and Museum in Washington, DC is a national facility dedicated to the service of the USCT during the American Civil War.

SOURCES

Civil War Trust: The Home Front – PDF

Wikipedia: United States Colored Troops

American Refugee Camp in Civil War Kentucky

National Archives: Preserving the Legacy of the United States Colored Troops

War Department General Order 143: Creation of the U.S. Colored Troops (1863)