Wife of Union Spy Timothy Webster

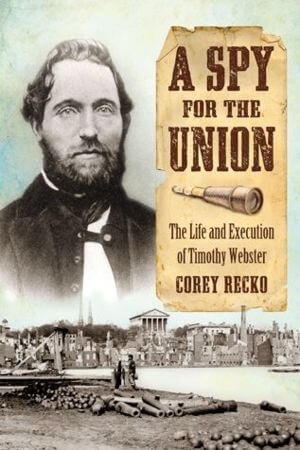

Charlotte’s husband Timothy Webster was an agent of the famous Pinkerton Detective Agency and a spy for the Union during the Civil War. Timothy Webster was Allan Pinkerton’s most trusted agent during the Civil War, and he was partially responsible for stopping an assassination attempt on president-elect Abraham Lincoln. Webster was later captured by Confederate forces and sentenced to death.

Charlotte’s husband Timothy Webster was an agent of the famous Pinkerton Detective Agency and a spy for the Union during the Civil War. Timothy Webster was Allan Pinkerton’s most trusted agent during the Civil War, and he was partially responsible for stopping an assassination attempt on president-elect Abraham Lincoln. Webster was later captured by Confederate forces and sentenced to death.

Marriage and Family

Timothy Webster was born in England in 1822, and his family immigrated to Princeton, New Jersey in the 1830s. Charlotte Sprowles married Webster on October 23, 1841 in Princeton, New Jersey. They had four children. As a young man, Webster learned the machinist trade. Sometime in the 1840s the Websters moved to New York City, and Timothy joined the city’s police force, which was too small for the large metropolis. A law passed in 1845 set up a larger department, laying the foundation for today’s New York City Police Department.

Pinkerton Detective

In 1853, Webster worked at the Crystal Palace exhibition, America’s first world’s fair, where he was introduced to detective Allan Pinkerton. Soon after, Webster accepted a job with Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency in Chicago and moved his family to Onarga, Illinois. When Webster joined the agency it was still relatively small, but it grew quickly and established offices throughout the nation. Many of the records of the Pinkerton agency were destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, but those that remain show that Webster established an impressive career as a private detective over the next few years. Pinkerton soon regarded him as one of his best detectives.

With female operative Hattie Lawton (aka Hattie Lewis) posing as his wife, Webster established himself in Perrymansville, Maryland in early 1861 He went undercover to infiltrate a secessionist militia. In February 1861, Abraham Lincoln was on his way to Washington DC for his inauguration as President of the United States when Webster learned of a plot to assassinate Lincoln while he was changing trains in Baltimore. Webster alerted Pinkerton, and they managed to sneak Lincoln through Baltimore on a different train and brought him safely to Washington without incident.

Civil War

Later that year the Civil War began, and Union General George B. McClellan hired Allan Pinkerton and his corps of detectives to gather intelligence for him. After the Battle of Bull Run in July 1861, McClellan was transferred to the Army of the Potomac and made its Commander-in-Chief. Pinkerton and his men then accompanied the general to Washington DC. Soon after, President Lincoln employed Pinkerton, and he organized the United States Secret Service and became its first Chief.

Life as a Union Spy

One of Pinkerton’s first duties was to send Timothy Webster south to gather information regarding troop numbers and movement, supplies, possible strategies and morale of the South. For several weeks, Webster had been visiting Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas and Mississippi, where he developed relationships with prominent people. At Memphis, he was offered the position of Colonel of the Second Arkansas Regiment, but declined, telling his friends he was going to Richmond to help with the war effort. With letters from leaders and officials of the states he had visited and detailed reports of conditions in those places, Webster made his way to Richmond.

Webster ingratiated himself into Richmond society, and he soon attracted the attention of Confederate Secretary of War Judah P. Benjamin who hired Webster as a courier for the Confederate’s ‘secret line’ between Washington, Baltimore, and Richmond. Therefore, Webster served as a double agent. He identified enemy agents in Washington and copied many of the secret letters he carried. This excerpt from the book On Hazardous Service: Scouts And Spies Of The North And South highlights Webster’s espionage activities:

Four times he made the trip from Baltimore to Richmond. He never made use of the Federal aid which was at his command, but he risked death from Union guns as surely as did any Confederate blockade-runner. In Baltimore he was looked upon as a hero; in Richmond, as a valued employee of the Confederate War Department; for, after his second trip there, he was employed by Judah P. Benjamin, Secretary of War, to carry despatches and the ‘underground mail,’ and to obtain information in Washington and Baltimore; on one occasion he received the personal thanks of the ‘great Secretary of the Confederacy.’ The passes furnished to Webster by the Confederate War Department enabled him to go wherever he wished, and he made a long journey into Kentucky and Tennessee. There seemed to be no limit to his audacity, no measure to his success.

Despite the danger of crossing back and forth through enemy lines so frequently, it was the perfect cover for a spy. It allowed him to travel freely to Richmond, the Confederate capital, where he and Hattie Lawton, once more posing as his wife, established themselves. They gained access to Confederate camps and earned the trust of many officiers. Webster carried official documents for several Confederate generals, who considered Webster a trusted messenger and a friend.

Webster’s next residence was in Baltimore, where he reconnected with the secessionists he had met while investigating the threats against Lincoln. Unfortunately, in February 1862, Webster fell ill. The thirty-nine year old spy was suffering from inflammatory rheumatism, the result of sleeping on the cold, wet ground on a previous journey South. Because Webster and Hattie had not been heard from, Pinkerton sent two operatives to find them – John Scully and Pryce Lewis. They found the couple at the Monumental Hotel in Richmond where Webster was confined to his bed unable to move.

Chase Morton, a man who was visiting Webster, had once lived in Washington, where Scully and Price had searched his family’s home. Morton sounded the alarm, and Scully and Lewis were immediately arrested and sentenced to death as spies. Incredibly, Webster was still so well respected that there was no suspicion whatever directed toward him. On the night before their execution, Scully requested a priest, who advised him to save himself. To save his own life, Scully confessed, implicating Webster as the head of the Secret Service for the United States Government in Richmond. Scully and Lewis were then released and avoided execution.

The Confederates arrested both Webster and Hattie Lawton. This excerpt appeared in an article in the National Tribune entitled ‘A Union Man in Richmond’:

A short time, comparatively, subsequent to the battles below Richmond between General George B. McClellan and General Robert E. Lee, a Northern man named Webster and his companion, name not remembered, were arrested on suspicion of being spies from Washington. They were examined by the Confederate authorities in Richmond and found guilty of the charge …

The affair caused much talk, and agitated the whole community for a season. I remember that there was much correspondence on the subject between the Federal authorities and Confederate, but nothing came of it. … There was much talk of retaliation on the part of the Federal authorities, but the suggested retaliation was abandoned eventually.

The extent to which Webster had infiltrated was embarrassing to Confederate officials. Therefore, the court-martial was not long in sentencing Timothy Webster to death and Hattie Lawton to a year in Richmond’s Castle Thunder Prison:

The Court having maturely considered the evidence adduced, and two-thirds concurring therein, they find the prisoner guilty of the charge. Whereupon, two-thirds of the Court concurring, it was adjustment that the accused ‘Suffer death by hanging.’

Hattie Lawton was sentenced to a year in Richmond’s Castle Thunder Prison. No spy on either side had thus far been sentenced to death. In the North, spies were simply kept in prison for a short time before releasing them, and many soon resumed their spying activities.

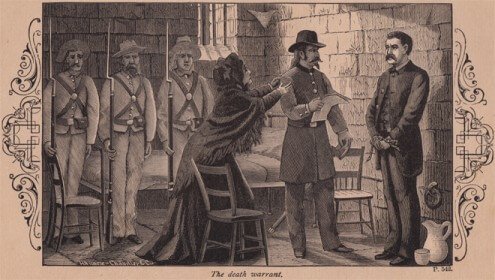

Image: Hattie Lawton pleads with Confederate authorities to honor Webster’s wish to be shot, rather than die a felon’s death by hanging; her pleas were in vain.

Execution of Timothy Webster

Upon receiving news of the death sentence, Pinkerton and President Lincoln both threatened that if Confederate authorities hanged Webster, the Union would respond by hanging a Confederate spy. Unfortunately, Confederate officials were not moved. By order of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, on April 29, 1862, still suffering from rheumatism, Timothy Webster was led to the gallows at Camp Lee in Richmond. Although he was in poor health, Webster met his fate bravely, his last words expressing a wish that “the Union might be preserved.”

The Richmond Whig published this notice on April 30, 1862:

HANGING OF A SPY. Timothy Webster, who was arrested as a spy, tried and convicted by a court martial, was, according to sentence taken to Camp Lee, yesterday [and] ‘hung by the neck until dead.’ Webster was the carrier of the ‘underground mail’ between this city and Washington, and having a special pass from the former Secretary of War, came and went at his pleasure.

Timothy Webster was the first spy to be executed in the American Civil War.

Allan Pinkerton made a promise back then to bring Webster’s body home. In 1871, with that mission in mind, he sent George Bangs and Thomas G. Robinson to Richmond to find Webster’s grave. With the help of Elizabeth Van Lew, a Southern-born Union spy, they located Webster’s grave, and Pinkerton gave him a proper burial in Northern soil.

Charlotte Sprowles Webster lived to be 89 years old before dying of paralysis.

SOURCES

A Union Man in Richmond

American Civil War Story: Timothy Webster

Timothy Webster: Spy of the Rebellion – PDF

On Hazardous Service: Scouts And Spies Of The North And South