Native American Mill Girl

During the 1830s and 1840s, Betsey Guppy Chamberlain (daughter of an Algonquian woman) worked in the textile mills of Lowell, Massachusetts and wrote stories for two workers’ magazines. A brave and pioneering author, Chamberlain wrote the earliest known Native American fiction and some of the earliest nonfiction about the persecution of Native people.

Image: Betsy Guppy Chamberlain, right

With another Lowell Mill girl

Early Years

Betsey Guppy was born December 29, 1797 in Wolfeboro, New Hampshire on the shore of Lake Winnipesaukee. She was the daughter of William Guppy and Comfort Meserve Guppy. She was of mixed race: American and Algonquian Indian. Betsey married Josiah Chamberlain on June 25, 1820, and they had two children; he died July 19, 1823. Unable to do the work alone, she was forced to sell their farm and work in the mills in Lowell, Massachusetts to support herself and her children. The mills paid good wages, but the hours were long.

Betsey married three more times, often reverting to the Chamberlain name between marriages. Records show that she joined the First Congregational Church in Lowell in March 1831 and married Thomas Wright in that church April 12, 1834.

Lowell Mill girl Harriet Robinson wrote this about Betsey when she came to work in the mills:

Mrs. Chamberlain was a widow, and came to Lowell with three children from some community, where she had not been contented. She had inherited Indian blood and was proud of it. She had long, straight black hair, and walked very erect, with great freedom of movement. One of her sons was afterwards connected with the New York Tribune.

Lowell System

During the early 1800s factories were established throughout New England, and the rivers powered the newly-developed manufacturing machines. Francis Cabot Lowell built the Boston Manufacturing Company in 1812 on the Charles River in Waltham, Massachusetts, the first cotton spinning and weaving mill in the United States. Beginning construction in 1821, Lowell expanded his operations by building a series of mills on the Merrimack River in Lowell, Massachusetts, a town named in his honor.

The term Lowell Mills refers to the many mills that operated in the town of Lowell during the 19th and early 20th centuries; the first opened in 1823. For the first time in the United States, these mills combined the textile processes of spinning and weaving in the same building; raw fibers were processed into high-quality cotton cloth. The workforce at these factories was three-quarters women.

Lowell Mill Girls

Lowell was a planned factory town, in which the company recruited young farm girls to work in the cotton mills. To attract the work force he needed, Francis Cabot Lowell established the Lowell System, in which the female factory workers lived in company dormitories, under the watchful eye of matrons hired to monitor the girls’ conduct. He believed that by providing a safe place to work, comfortable living conditions, and a socially positive environment he could ensure a steady supply of labor.

In the early days, the mill girls were paid well but they worked 70 or more hours each week in hot and difficult environments. To compensate, mill owners created educational and cultural opportunities for the mill girls, including Bible study classes. The town of Lowell boasted libraries and bookstores, evening schools and lectures, concerts and other social events. The experiment worked well at first. By the early 1830s, young single women from rural New England comprised the majority of workers in Massachusetts textile mills.

Increased competition in the textile industry forced factory owners to cut wages and lengthen hours to stay profitable and meet demands. In 1834 Lowell cut his workers’ wages by 25 percent but did not reduce hours, and 600-700 women went on strike. They organized a labor union they called the Factory Girls Association, but their efforts were unsuccessful. The mill girls struck again when their housing rates were raised, but they were unable to support themselves and were back on the job within a month.

In 1836 some 1200-1500 women walked out and petitioned the Massachusetts legislature to limit their workday to 10 hours. The law did not pass, but the incident convinced factory owners that the Mill Girls were too much trouble, and they began hiring the poor Irish immigrants who were then pouring into the state.

Image: Lowell Mill Girl Spinning Fabric and Bobbin Girl by Winslow Homer

The Workplace

This excerpt from The Harbinger magazine tells of the life of a mill girl:

We have lately visited the cities of Lowell and Manchester and have had an opportunity of examining the factory system. … We could scarcely credit the statements made in relation to the exhausting nature of the labor in the mills, and to the manner in which the young women – the operatives – lived in their boarding houses, six sleeping in a room, poorly ventilated.

We went through many of the mills, talked particularly to a large number of the operatives, and ate at their boardinghouses, on purpose to ascertain by personal inspection the facts of the case. … We assure our readers that very little information is possessed, and no correct judgments formed, by the public at large, of our factory system, which is the first germ of the industrial or commercial feudalism that is to spread over our land. …

In Lowell live between seven and eight thousand young women. … The operatives work thirteen hours a day in the summer time, and from daylight to dark in the winter. At half past four in the morning the factory bell rings, and at five the girls must be in the mills. A clerk, placed as a watch, observes those who are a few minutes behind the time, and effectual means are taken to stimulate punctuality. …

At seven the girls are allowed thirty minutes for breakfast, and at noon, thirty minutes more for dinner… But within this time they must hurry to their boardinghouses and return to the factory, and that through the hot sun or the rain or the cold. A meal eaten under such circumstances must be quite unfavorable to digestion and health, as any medical man will inform us. After seven o’clock in the evening the factory bell sounds the close of the day’s work. …

Now let us examine the nature of the labor itself, and the conditions under which it is performed. Enter with us into the large rooms, when the looms are at work. … The din and clatter of these five hundred looms, under full operation, struck us on first entering as something frightful… After a while we became somewhat used to it, and by speaking quite close to the ear of an operative and quite loud, we could hold a conversation and make the inquiries we wished.

The girls attended upon an average three looms; many attended four, but this requires a very active person, and the most unremitting care. However, a great many do it. Attention to two is as much as should be demanded of an operative. This gives us some idea of the application required during the thirteen hours of daily labor. The atmosphere of such a room cannot of course be pure; on the contrary, it is charged with cotton filaments and dust, which, we are told, are very injurious to the lungs.

On entering the room, although the day was warm, we remarked that the windows were down. We asked the reason, and a young woman answered very naively, and without seeming to be in the least aware that this privation of fresh air was anything else than perfectly natural, that “when the wind blew, the threads did not work well.”

So live and toil the young women of our country in the boardinghouses and manufactories which the rich and influential of our land have built for them.

Lowell Offering

The mill girls wrote for a magazine called the Lowell Offering, a monthly periodical that published poetry, prose and fiction between 1840 and 1845. The Offering was initially organized by the Reverend Abel Charles Thomas, pastor of the First Universalist Church in Lowell. The contents of the magazine alternated between serious and humorous. It initially consisted of articles from local self-help and literary societies, but later received contributions from female textile employees.

Harriet Farley had joined the workforce in 1838; although she was working 11 to 13 hours a day, and living in a crowded company boardinghouse, she felt a sense of freedom to “read, think and write … without restraint.” She was soon contributing articles to the Lowell Offering, and in 1842 along with Harriot Curtis became its co-editor. The magazine ceased publication in 1845, but was revived in 1848 as the New England Offering (1848-1850), gathering contributions from working women throughout New England.

With her pen …

Betsey Guppy Chamberlain, a half-Algonquian mill girl, published poetry and thirty-three works of prose in the Lowell Offering between 1841 and 1842, using the pseudonyms Betsey, B.C., Jemima, and Tabitha. She primarily wrote sketches of village life and legends, which illustrate her powers of observation and bring her characters to life.

In her writings, Betsey expressed the then-radical ideas that Indians deserved to be well treated and that women should be paid the same as men. A few of her essays, including The Indian Pledge and A Fire-Side Scene, are among the earliest protests against the persecution of indigenous peoples to be published by a Native woman. A Fire-Side Scene is highly critical of the poor treatment of Native peoples by the United States government.

Other contributors incuded Eliza G. Cate, Abba A. Goddard, Lucy Larcom and Harriet Hanson Robinson, who gave this opinion of Betsey:

Mrs. Chamberlain was the most original, the most prolific, and the most noted of all the early story-writers. Her writings were characterized, as Mr. Thomas says, ‘by humorous incidents and sound common sense,’ and is shown by her setting forth of certain utopian schemes of right living.

Betsey Chamberlain also wrote about gender and class issues. In a story called A New Society she wrote of a setting where new rules of living are adopted:

1. Resolved, That every father of a family who neglects to give his daughters the same advantages for an education which he gives his sons, shall be expelled from this society, and be considered a heathen.

2. Resolved, That no member of this society shall exact more than eight hours of labor, out of every twenty-four, of any person in his or her employment.

3. Resolved, That, as the laborer is worthy of his hire, the price for labor shall be sufficient to enable the working-people to pay proper attention to scientific and literary pursuits.

4. Resolved, That the wages of females shall be equal to the wages of males, that they may be able to maintain proper independence of character, and virtuous deportment.

The Lowell Offering attracted hundreds of subscribers in New England and other states. As its popularity grew, mill workers contributed poems, ballads, essays and fiction, which often reflected situations in their lives. Later issues included an essay about suicide among the Lowell girls.

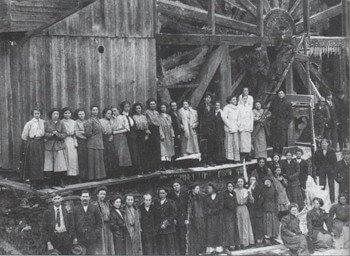

Image: The Beehive, built in 1839

Boarding house where mill girls lived Lowell, Massachusetts

Betsey Chamberlain married Charles Boutwell March 26, 1843. He was a widowed farmer with children of his own; they moved to Illinois and began farming. However, she returned to Lowell in 1848, possibly to earn money to support the farm. She published several short pieces in the new workers’ magazine, the New England Offering, between December 1848 and February 1850. Soon after, Betsey left the mills and returned to Illinois. Unfortunately, her writings stopped when her employment at Lowell ended.

Records indicate that Charles Boutwell died during the Civil War, on October 30, 1863. Betsey married I.A. Horn of Kentucky three years later, November 21, 1866; nothing is known of their marriage.

Betsey Guppy Chamberlain Wright Boutwell Horn died at the age of eighty-eight.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Lowell Mills

Wikipedia: Lowell Offering

Female Workers of Lowell (1836)

Wikipedia: Betsey Guppy Chamberlain

Encyclopedia.com: Lowell System of Labor

Betsey Guppy Chamberlain Promotes the Radical Notion That Indians Are People

Betsey Guppy Chamberlain was said to have “inherited Indian blood,” but it is not known for sure whether this inheritance derived from her maternal or paternal ancestors, or both.

She was born in Brookfield, N.H. — not in Wolfeboro.

It is not known whether Betsey Guppy Chamberlain continued writing or publishing after leaving Lowell, Massachusetts. I have not found any such writings, but I continue to search for them. She could have continued to publish anonymously.

I have never heard of a residence for Lowell mill workers called “The Beehive.” Please supply the source of this image.

The photograph purported to depict Betsey Chamberlain is not a photograph of her, as far as I know. Please give the source of this attribution. I have not found any portrait of Betsey Chamberlain.

The New England Offering was revived in September, 1847.

The Operatives’ Magazine was another workers’ periodical published simultaneously with early issues of The Lowell Offering.

It is not accurate to characterize Betsey Guppy Chamberlain as a “half-Algonquian” woman. It is not known how much Native ancestry she possessed.