Member of the Tragic Donner Party

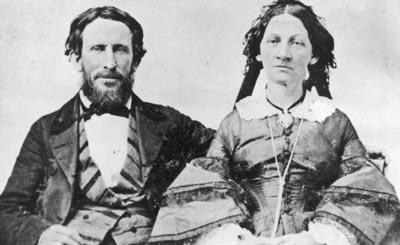

James and Margaret Reed

In 1846, Margaret Reed and husband James left Illinois on their way to the promised land of California, where they hoped to begin a new life, but their migration did not go smoothly. An early snowstorm trapped the travelers in the treacherous passes of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. This is more the story of the Reeds than the Donners because the Reeds left diaries and letters about that tragic journey.

California Fever

James Frazier Reed was one of the organizers of the wagon train that would become known as the Donner Party. Born in Ireland, he came to the United States as a young boy with his widowed mother. Reed had made a fine life for himself and his family in Illinois as a farmer and businessman, but in 1846 James and Margaret Reed caught California Fever.

To make the trip as easy as possible for Margaret, who suffered from terrible headaches, James Reed built a two-story wagon. He outfitted their main wagon with an iron stove, spring-cushioned seats and bunks for sleeping. Dubbed the Palace Car by their fellow travelers, it was by all accounts the largest and fanciest vehicle anyone had built for westward migration. Eight oxen were required to pull the luxurious wagon, and its sheer size was a hindrance when the trail got rough. Reed also stocked two support wagons with fine food and liquor.

Although the Reeds were anxious to begin a new life in California, the departure from Illinois, leaving friends they had made there, was difficult. James and Margaret Reed were very sad to leave their friends behind. Their twelve-year-old daughter Virginia wrote in her diary:

My father, with tears in his eyes, tried to smile as one friend after another grasped his hand in a last farewell. Mama was overcome with grief. At last we were all in the wagons. The drivers cracked their whips. The oxen moved slowly forward and the long journey had begun.

On the Trail

On April 16, 1846, 32 men, women and children in nine brand new covered wagons left Springfield, Illinois on the 2500 mile journey to California, which should take four months. In his forties, James Reed was traveling with his wife Margaret and their four children – Virginia, Patty, James and Thomas – as well as two hired servants. Margaret suffered from terrible headaches, and Reed hoped her condition would improve in the new climate. Reed’s mother-in-law Sarah Keyes was so sick with consumption she could barely walk, but she refused to be separated from her only daughter.

California Trail

More than 250,000 people followed the California Trail to the gold fields and rich farmlands during the 1840s and 1850s – the greatest mass migration in American history. After the Raft River crossing, the pioneer’s path split from the Oregon Trail, and those bound for the Golden State turned south. The trail then meandered through the corner of Utah, then along the Humboldt River in Nevada.

Hastings Cut-Off

The pioneers reached Fort Laramie on June 27, 1846, one week behind schedule. There, James Reed ran into James Clyman, an old friend from Illinois who had just traveled the new route coming east with trail guide Lansford Hastings, who touted a new cut-off in his book The Emigrants’ Guide to Oregon and California. Hastings stated that by bearing south rather than north around the Great Salt Lake, the pioneers would shorten their journey by 350-400 miles and reduce their travel time by three weeks.

However, James Clyman told Reed that the Hastings Cut-Off saved very little time and the road, barely passable on foot, would be impossible with wagons. But James Reed wholeheartedly believed in the shortcut. Anxious to reach their destination quickly, Reed ignored Clyman’s warning. On July 19 the train split, with the majority of the large caravan taking the California Trail to Fort Hall in Idaho.

Before departing from Fort Laramie, the group of pioneers who preferred taking the Hastings Cut-off elected sixty-year-old farmer George Donner as the wagon train’s captain, and the expedition would take on his name as well. Traveling the southerly route, the Donner Party reached Fort Bridger, Wyoming on July 28. Jim Bridger assured the Donner Party that the Hastings Cut-off was a good route.

On July 31, they left Fort Bridger. The group now included 74 people in twenty wagons and for the first week they made good progress, traveling ten or twelve miles per day. On August 11, the wagon train began the arduous journey through the Wasatch Mountains, where they had to clear trees and other obstructions so the wagons could pass. They lost valuable time and energy, traveling only eight miles in six days. Before long, morale began to sink.

On August 30, they reached the Great Salt Lake Desert, a large dry lake in northern Utah. According to Hastings, it should take two days to cross the Desert, but it took five days. Several wagons mired down in the salt-crusted mud and had to be left behind. Thirty-two of the oxen that pulled the wagons died, as well as some cattle. The pioneers had made a communal decision to attempt the cut-off, but when it cost them five weeks instead of saving three, they began to blame Hastings and Reed.

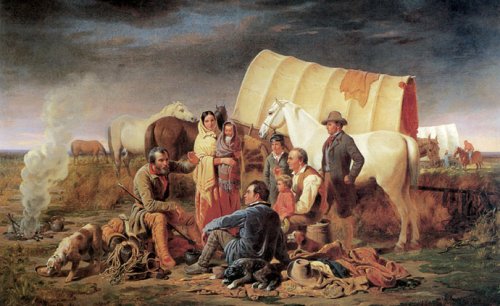

Image: Advice on the Prairie

By William Tylee Ranney, 1853

Library of Congress

Back on the California Trail

The Donner Party finally reached the junction with the California Trail on September 20, and for the next two weeks they traveled along the Humboldt River. On October 12, their oxen were attacked by Paiute Indians, killing 21 one of them with poison tipped arrows, further depleting their draft animals. Due to the trials they had endured, the Party split into splintered groups, each looking out for themselves and distrustful of the others. As they became more disillusioned by the journey, tempers flared.

Reed Banished

In early October, supplies were low, animals were dying, and days were hot as they traveled through central Nevada. A young teamster named John Snyder lost his temper while attempting to drive his wagon up a steep slope, and out of frustration he began beating his oxen with a whip. When James Reed tried to intervene, the young man turned the whip on him. Possibly in self defense, Reed stabbed him in the chest with a knife, and Snyder died soon after.

That evening the pioneers gathered to discuss what was to be done. Witnesses had seen Snyder hit James Reed – some claimed that he had also hit Margaret Reed, but Snyder had been popular and Reed was not. Some wanted to hang Reed for his actions, but others defended him. They eventually reached a compromise and banished Reed from the Donner Party. Initially, he refused to accept their decision, but finally agreed to go ahead to Sutter’s Fort in the Sacramento Valley for supplies.

Reed was allowed to leave the camp without his family, who were to be taken care of by the others. He departed the next morning, alone and unarmed, but his stepdaughter Virginia rode ahead on horseback and secretly provided him with a rifle and food. Reed rode on alone, crossing the Sierra Nevada just ahead of the early snows.

Snowbound

The Donner Party had chosen multiple times to take shortcuts to save distance instead of following the traditional Oregon and California Trails, which caused many delays. Infighting and a disastrous crossing of the Utah salt flats had also lengthened their journey.

When they reached the Sierra Nevada Mountains at the end of October, an early snowstorm brought the settlers to a halt about 1,200 feet below the summit of the Sierra Nevada. They were only 90 miles east of their final destination, Sutter’s Fort near Sacramento. The pioneers attempted to force their few remaining wagons, oxen, and supplies over what is now known as Donner Pass, but due to freezing conditions and the lack of any pre-existing trail, they failed.

Demoralized and low on supplies, about three quarters of the emigrants camped at the east end of Truckee Lake, where level ground and timber were abundant. They built rude shelters, hoping to resume their journey, but they were forced to slaughter their oxen for food. As the winter wore on, many of the emigrants starved to death.

Donner Party member Patrick Breen wrote in his diary November 20, 1846:

Came to this place on the thirty-first of last month; went into the pass; the snow so deep we were unable to find the road, and when within three miles from the summit, turned back to this shanty on Truckee Lake; [Charles] Stanton came up one day after we arrived here; we again took our teams and wagons, and made another unsuccessful attempt to cross in company with Stanton; we returned to this shanty; it continued to snow all the time. We now have killed most part of our cattle, having to remain here until next spring, and live on lean beef, without bread or salt. It snowed during the space of eight days, with little intermission, after our arrival, though now clear and pleasant, freezing at night; the snow nearly gone from the valleys.

On Thanksgiving, snow began falling again, eventually accumulating 30 feet, and the pioneers killed the last of their oxen for food on November 29. The very next day, five more feet of snow fell, and any hopes they had of continuing their journey were dashed. They had come 2,500 miles in seven months only to lose their race with the weather by one day.

On January 4, 1847, Breen wrote in his diary:

Mrs. Reed and Virginia, Milton Elliott, and Eliza Williams started a short time ago with the hope of crossing the mountains; left the children here. It was difficult for Mrs. Reed to part with them.

Breen diary, January 15, 1847:

Mrs. Reed and the others came back; could not find their way on the other side of the mountains. They have nothing but hides to live on.

Rescue!

In early February 1847 the citizens and naval officers of San Francisco funded a rescue party. James Reed rounded up men and supplies in the Sonoma and Napa Valleys, then headed up into the mountains. On February 19, 1847, the first team of rescuers trudged through the still snow-filled passes and reached Truckee Lake, finding what appeared to be a deserted camp until the ghostly figure of a woman appeared. Four relief parties rescued forty-seven people who had survived the ordeal, Margaret Reed and her four children among them.

However, the nightmare was still not over for many survivors of the Donner Party. Not everyone could be taken out at one time, and since pack animals could not navigate the fields of deep snow, few food supplies arrived. Several more relief parties arrived in March and April. In the meantime, the situation at the Truckee Lake camp was just as difficult as ever. Patrick Breen wrote in his diary in late February 1847, shortly after the first rescue team had departed:

Thursday 25th, froze hard last night fine and sunshiny today wind W. Mrs Murphy says the wolves are about to dig up the dead bodies at her shanty; the nights are too cold to watch them, we hear them howl. Friday 26th, froze hard last night today clear and warm Wind SE: blowing briskly. Martha’s jaw swelled with the toothache: hungry times in camp, plenty hides but the folks will not eat them, we eat them with a tolerable good apetite. Thanks be to Almighty God. Amen.

Mrs. Murphy said here yesterday that she thought she would Commence on Milt [one of the dead] and eat him. I do not think she has done so yet; it is distressing. The Donners told the California folks that they commenced to eat the dead people 4 days ago, if they did not succeed that day or next in finding their cattle, then under ten or twelve feet of snow and did not know the spot or near it, I suppose they have done so ere this time.

The extent of the Donner Party tragedy would not be known for several weeks. The final tally revealed that two-thirds of the men had perished, while two-thirds of the women and children lived. A total of forty-one individuals died, while forty-six survived. Many survivors were insane or barely clinging to life.

Image: Map of Donner Party Route, including the Hastings Cut-Off

News of the Donner tragedy quickly spread across the country. Newspapers printed letters and diaries and accused the travelers of bad conduct. The surviving members had differing viewpoints and recollections so what really happened to the Donner Party has never been completely clear.

The reunited Reed family recuperated in the Napa Valley for many weeks. Margret Reed had always been frail in health, but when disaster struck in the mountains, she became “the bravest of the brave,” as her daughter Virginia remarked. All of the Reed children survived the ordeal in the mountains.

During the time he had spent around San Jose while waiting to assemble a search party, James Reed had recognized the value of the rich, well-watered bottomland in the long fertile valley nearby. Once the Reeds were well enough to travel, James leased orchards at Mission San Jose and moved his family there. In the summer of 1847, the Reeds gathered and dried pears, apples, figs and quince; they shipped the fruit to Hawaii, trading it for sugar, cocoa, coffee and rice.

Reed was elected to a new council at San Jose and moved his family into the Pueblo, renting the only space available – a one-room adobe abode with a dirt floor. Margaret gave birth to their fifth child there on February 6, 1848, less than a year after her escape from the snowbound passes of the Sierra Nevada. Willie followed in 1850 but lived only nine years.

In the spring of 1848, Reed joined the Gold Rush and profited from his rich diggings near Placerville, returning home in the fall. By the time President James Polk informed the rest of the world of the far west’s riches in December 1848, James Reed had become active in his community. Soon after, the family settled on a 500-acre ranch in San Jose, where he and Margaret had decided to settle and raise their children.

Margaret Reed’s sick headaches did not return, but her health was never robust. She died November 25, 1861 in San Jose, at the age of 47. James Reed died in San Jose on July 24, 1874.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Donner Party

Legends of America: The California Trail

Legends of America: Donner Party Tragedy

The Bad Luck and Good Luck of James Frazier Reed

Eyewitness to History: Tragic Fate of the Donner Party

Those were my ancestors on my Dads’ side. It explains alot.