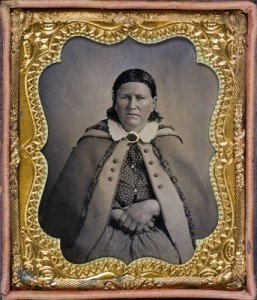

Texas Rancher and Pioneer Female Trail Driver

In the mid-1800s, cattle ranching was becoming big business in Texas, but not all ranchers were men. Margaret Borland was one of the very few frontier women who ran ranches and handled her own herds. She drove 1000 head of Texas Longhorn cattle up the Chisholm Trail from south Texas to Wichita, Kansas – a tough trip for the four young children she was forced to take with her.

Early Years

Margaret Heffernan was born April 3, 1824 in New York City. Her parents, both born in Ireland, had sailed to America a few years before Margaret’s birth. Her father was a candlemaker who struggled to provide a living for his family. When land agent John McMullen came to New York telling tales of lucrative opportunities available in Texas, the Heffernans agreed to join his colony.

Margaret was five years old in 1829, when she sailed with her family down the East Coast headed for Texas. They settled on the wild prairies around San Patricio in south Texas, and her father became a successful rancher.

Margaret’s father was killed by General Jose Urrea’s forces during the Texas Revolution (1835-1836) just before the Texas invasion by Santa Ana. Mrs. Heffernan, along with her two daughters and two sons, loaded their possessions into a small cart and fled the advancing armies in search of safety in the fort at Goliad. Margaret, 12 years of age, and her siblings spoke nothing but Spanish so they could pass as Mexican children, which probably saved their lives.

Marriage and Family

After the Texas war for independence, the Heffernan family returned to their ranch at San Patricio. When Margaret was nineteen she met Harrison Dunbar and they were soon married. Shortly after Margaret gave birth to a daughter, Harrison Dunbar was killed in a pistol duel in the streets. Margaret was left a widow and single parent at the age of twenty.

She married Milton Hardy in 1845, and they settled down on the 2,912 acres of land they owned. Margaret gave birth to a son and three daughters, one of whom died in infancy. Again tragedy struck, and her second husband succumbed to cholera in 1855. Despite her devoted care, she also lost her infant son in the same epidemic.

Margaret’s younger brother came to help her run the ranch until she was married for a third time in 1858 to Alexander Borland, who was said to be the wealthiest rancher in Victoria, Texas. Identified in the 1860 Census as 42, a native of North Carolina, Borland owned real estate valued at $14,500, a personal estate of $28,000, and 12 slaves. During their marriage, Margaret gave birth to four more children.

Alexander and Margaret partnered to build one of the largest ranches on the Texas coast during the state’s booming cattle business. By 1860, they owned 8,000 head of Texas Longhorn cattle. In the ensuing years, they began to hear about trail drives from Texas to Kansas, and dreamed of taking a herd of their own someday. However, the yellow fever epidemic of 1867 took a terrible toll on her family. Before it was over, she had lost her third husband, three daughters, a son, and an infant grandson. Only three of her seven children remained alive.

Cattle Business

After her husband’s death, Margaret Borland threw herself into the role of sole owner and manager of a large ranch. She hired more hands to do the physical labor, while she participated in the cattle business, buying and selling livestock, and increasing her herd to 10,000 head. That same year Margaret paid the U.S. government $9.17 to become a licensed butcher in Victoria. Her son-in-law Victor Rose, Victoria Advocate newspaper editor and historian, wrote that Margaret was:

… a woman of resolute will, and self-reliance, yet she was not one of the kindest mothers. She had, unaided, acquired a good education, her manners were lady-like, and when fortune smiled upon her at last in a pecuniary sense, she was as perfectly at home in the drawing room of the cultured as if refinement had engrafted its polishing touches upon her mind in maiden-hood.

Cattle Drives

When the Civil War ended, the state’s only assets were its countless Texas Longhorn cattle. Cattle drives were then becoming an important part of the economy in the American West, particularly between 1866 and 1886, when millions of cattle were herded from Texas to railheads in Missouri and Kansas for shipment to stockyards and packing houses in the North. The long distances traveled on these drives, and the necessity for periodic rests for riders and animals, led to the establishment of several cow towns across the frontier.

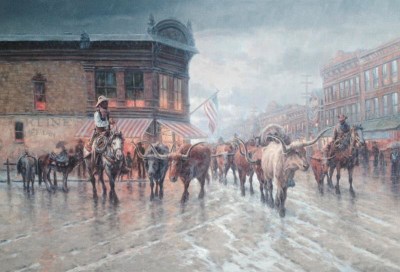

Image: The Last Crossing – Cattle Drive

By Persis Clayton Weirs

Trail bosses had to strike a balance between speed and the weight of the cattle. Cattle could travel as far as 25 miles a day, but they would lose too much weight on the drive, making them hard to sell when they reached the railheads. Usually they were taken about 15 miles each day, and were allowed periods to rest and graze both at midday and at night. At that pace, a herd could maintain a healthy weight, but it would take up to two months to travel from a home ranch to a railhead.

Chisholm Trail

During the Civil War, while many Texans were away fighting for the Confederacy, the cattle multiplied, but cattle drives did not start in earnest until after the Civil War, and the Chisholm Trail was the major route out of Texas. Longhorn cattle driven north provided a steady source of income that helped the impoverished state recover from the War. From 1867 to 1887, more than 14 million head of longhorn cattle were driven from Texas to newly formed cow towns in Kansas. And along the 1,000-mile Chisholm Trail, a new folk hero was born: the American cowboy.

The first herd to follow the future Chisholm Trail to Kansas belonged to O. W. Wheeler, who planned to winter them on the plains, and then move them on to California. At the North Canadian River he saw wagon tracks and decided to follow them. Those tracks had been made by Scot-Cherokee Jesse Chisholm, who in 1864 began hauling trade goods to his trading post near Wichita, Kansas.

Though it was originally applied only to the trail north of the Red River, Chisholm’s name was soon given to the entire trail from the Rio Grande to central Kansas. The earliest known references to the Chisholm Trail in print was in the Kansas Daily Commonwealth of May 27, 1870. On April 28, 1874, the Denison Daily News mentioned cattle going up “the famous Chisholm Trail.”

Cattle on the Chisholm Trail did not follow a clearly defined trail except at river crossings. When dozens of herds were moving north at the same time, it was necessary to spread them out to find enough grass. Under those circumstances, the animals were allowed to graze along for only ten or twelve miles a day and were never pushed except to reach water. When conditions were favorable longhorns actually gained weight on the trail, and those that ate and drank their fill were unlikely to stampede.

However, by the 1880s, the great cattle drives had largely disappeared and the Chisholm Trail was soon being covered by the dusty desert winds. The railroads had created the cattle drives, and the railroads would end them as track was laid throughout Texas, making the great drives obsolete. The Chisholm Trail glory days were over, but in its brief existence the hooves of more than five million cattle and a million mustangs had passed along its rutted paths and rocky river crossings in the greatest migration of livestock in world history.

But ranching still brought profits and the Plains were better suited for grazing than for agriculture and western ranchers continued supplying beef for national markets. After Indian tribes no longer posed a threat and the buffalo population had been decimated, ranches began to spring up all over the Plains; most were stocked with Texas Longhorns and manned by Texas cowboys.

First Female Trail Boss

In the early spring of 1873, the San Antonio market offered $8.00 per head of cattle; Kansas was paying $23.80. Margaret Borland weighed her options and decided to drive 1,000 head of cattle up the Chisholm Trail. Having lost her older children to yellow fever six years earlier, no one was left at home to care for her three remaining children – a daughter aged eight, two sons aged fourteen and fifteen and a six year old granddaughter. Though their presence would likely make the trip more difficult, she was forced to take them with her.

At least four women in history have been designated Cattle Queens, but they were accompanied on the trail by their husbands. Margaret Borland was likely the only woman to run her own cattle drive from Texas to Kansas.

As trail boss she had the ultimate authority on the trip, but trail bosses faced many difficulties. They had to cross major rivers and innumerable smaller creeks, plus canyons, badlands and low mountain ranges. The weather was less than ideal, with freezing rains at night, lightning storms and torrential showers, and desert dust storms.

Image: Trail Drive Reprieve

By Jack Terry

In addition to these natural dangers, rustlers and occasional conflicts with Native Americans erupted. The natives demanded that trail bosses pay a toll of ten cents per head of cattle for the right to cross Indian lands. And half-wild Texas Longhorn cattle were contrary and prone to stampede with little provocation.

Margaret Borland reached Wichita, Kansas two months after leaving her ranch in south Texas, and took a room at a boarding house. Word quickly spread through town of her amazing accomplishment. The Wichita Beacon newspaper noted her arrival June 4, 1873:

Mrs. T.M. Borland of Texas, with three children, is stopping at the Planter house. She is the happy possessor of about one thousand head of cattle, and accompanied the herd all the way from its starting point to this place, giving evidence of a pluck and business tact far superior to many of the “lords.”

Death At Wichita

After successfully reaching Wichita, Kansas, Margaret Borland was suddenly consumed by an illness known as trail fever, one month after her remarkable Chisholm Trail journey. She had not sold her cattle yet. One newspaper article remarked that she had “become endeared to many in town on account of her lady-like character.”

Margaret Borland died July 5, 1873 at the age of 49 and her body was returned to Texas for burial. She left no diary or letters to tell us more about her life, but she became a legend up and down the Chisholm Trail.

SOURCES

TSHA: Chisholm Trail

Bullock Museum: Margaret Borland

American Yawp: Conquering the West

Petticoats and Pistols: Rancher and Woman Trail Driver

Margaret Heffernan Borland: Rancher and Woman Trail Driver

I am just starting to educate myself on the amazing Mrs Borland – but I am reading conflicting reports, do we know for sure if she was or was not pregnant during this trail drive? Tks for helping me learn the facts of this incredible woman’s effort.