Union Newspaperwomen in Confederate Virginia

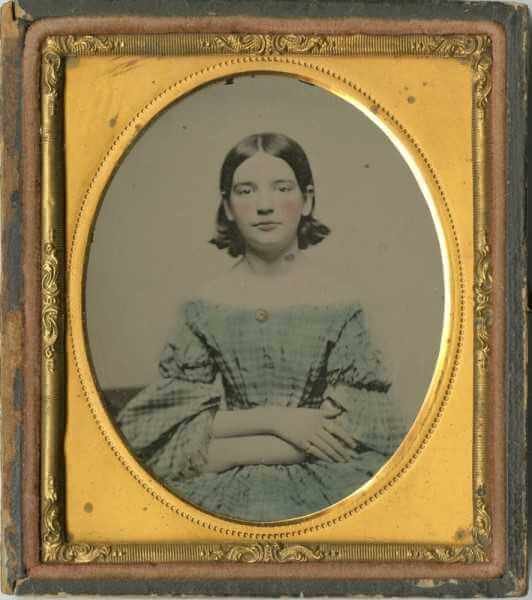

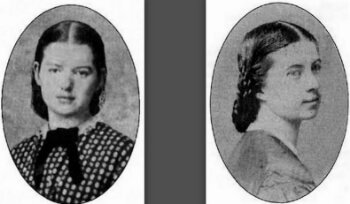

Image: Lida and Lizzie Dutton

Image: Lida and Lizzie Dutton

During the years preceding the Civil War, Quakers in Loudoun County, Virginia lived in a heated political situation. After their state seceded from the Union, they struggled to remain pacifists in the presence of Confederate troops. But three girl journalists in the town of Waterford had no problem asserting their support for the Union.

Educating the Dutton Girls

Like most Quakers, John and Emma Dutton of Loudoun County, Waterford, Virginia believed that girls should be as well educated as boys. The Duttons home schooled their daughters Emma Eliza (called Lida) and Elizabeth (known as Lizzie) at home, and encouraged them to exercise full use of their minds. Their cousin Sarah Steer studied at a Ladies Academy in Philadelphia.

In a letter from 1864, John Dutton wrote:

I take great pride in my childrens’ writing. I want each to exert themselves in this particular branch of learning and now is the time whilst thy little fingers are limber… Make it a rule to study – to think – weigh thy thoughts well for thy self. Don’t conclude things are right just because the mass of the people say so.

Waterford Literary Society

Before the war, Lida, Lizzie and Sarah were members of the Waterford Literary Society. They wrote essays which were read aloud to the group, gently critiqued, and then recorded in a large bound book. The Society’s volumes are now held at the Thomas Balch Library in Leesburg. An anonymous note in the Society Essays reads: “Take life as it is, a real matter-of-fact thing, and do it justice.”

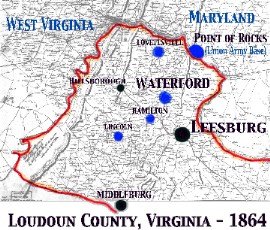

The Civil War in Loudoun County

At the beginning of the war, most Quaker men left Waterford for nearby Maryland, a Union state, in order to avoid being forced to enlist in the Confederate Army. James Dutton, brother of Lida and Lizzie, risked the discipline of the pacifist Quaker Church to stay and join the Union Army. Lida, Lizzie and Sarah managed to hold together the farms and businesses their fathers and brothers had left behind.

No battles were fought in Waterford, but in 1862 Confederate troops arrived in the town to forage and then burn the village down. Resident Rachel Means ran to the only man who still had a horse. When the man would not ride to Union General John Geary stationed nearby and ask for help, Means stole his horse and made the ride herself. Waterford was saved.

In January 1864, Federal troops enforced a blockade along the Potomac River to prevent smuggling into the Confederacy, but it also prevented necessities from reaching Waterford. Although the girls’ fathers, John Dutton and Samuel Steer, had fled to Maryland and now filtered much needed supplies back to the town, the citizens of Waterford were suffering from a lack of necessities.

The Waterford News

The three young ladies previously mentioned, Lida, now 19, Lizzie, 24, and Sarah, 26, decided to express their support for the Union by publishing a defiantly pro-Union newspaper inside the Confederacy. Their objectives were to “cheer the weary soldier, and render material aid to the sick and wounded” by donating the proceeds to the U.S. Sanitary Commission. They called it The Waterford News.

With no paper and no money, getting a newspaper out of Confederate Virginia was no small task. Draft copies of the newspaper had to be smuggled across the Potomac River into Maryland where it was printed by the Baltimore American, whose editor was an old friend of John Dutton. But the girls handled the reporting, writing and editing.

The first four-page edition of The Waterford News appeared on May 28, 1864 and continued monthly through April 1865. Although by 1864 the main lines of battle had passed far south of Loudoun County, publishing an anti-Southern paper took courage. Confederate partisans – particularly Colonel John Singleton Mosby and his troops – aggravated the citizens of Waterford throughout the war.

In the face of war, these young ladies still wanted to be proud of their appearance. This notation appeared in the first edition:

Great distress is felt by the ladies of this vicinity at not being able to appear at meeting in new bonnets, dresses and wrappings, owing to the stringent blockade.

The girls published this editorial in the July 2, 1864 edition of The Waterford News, soon after Lizzie Dutton received news that her fiance, Lt. David Holmes, had been killed in the Battle of Petersburg:

Let not kind words, loving tones, and love of good deeds cease to find a place in our hearts. Now, if ever, is the time to ‘cast bread upon the waters,’ when tired and weary ones are all around us, and starvation stares so many in the face; when loved ones are struggling with pain, and joy and happiness are hidden in the distance; when hope leaves us and misery looks at us with hollow eyes. Let us be up and doing – old and young – we have no time to idle; every quickly flitting moment is to be improved, every space filled up.

This prophetic editorial appeared on July 2, 1864 as well:

Many threats have been made about burning our houses over our devoted heads. But Waterford is still standing. And we trust it may stand long in the future to remind other generations that in its time-honored walls once dwelt as true lovers of their country as ever breathed the breath of life-long-suffering – but stood faithful to the end.

A Raid on Loudoun County

Late in November 1864, General Ulysses S. Grant authorized a raid on Loudoun County, which locals called The Burning Raid. The Waterford News called it The Fury Order. Grant hoped that if they burned out the farms that were providing forage to Confederate Colonel Mosby and his men, they would be incapacitated, if only temporarily. Grant ordered barns to be burned, livestock killed or driven off, and men under 51 capable of bearing arms to be siezed.

So pro-Union Loudouners had the unpleasant task of watching the Union army destroy in less than a week what they had been hiding from bushwhackers and Confederates for four years. Between November 27 and December 2, the skies over western Loudoun were dark with the smoke of hundreds of fires.

So pro-Union Loudouners had the unpleasant task of watching the Union army destroy in less than a week what they had been hiding from bushwhackers and Confederates for four years. Between November 27 and December 2, the skies over western Loudoun were dark with the smoke of hundreds of fires.

While Loudoun Quakers struggled to remain patriotic, The Burning Raid did have the intended affect on the Confederate populace: it broke their spirit of rebellion.

There were many indications that the soldiers were not happy in their work as arsonists. Perhaps to assuage their guilt, an editorial in the January 28, 1865 edition of The Waterford News stated:

We do not believe, if our Government had been as well acquainted with us as we are with ourselves, the order for the recent burning would have been issued; but having suffered so much at the hands of the Rebels ever since the commencement of this cruel war, we will cheerfully submit to what we feel assured our Government thought a military necessity.

By the spring of 1865, the young newspaperwomen had written and published at least eight issues of The Waterford News. President Abraham Lincoln read two of those editions, after Private Schooley of the 11th Regiment, Maryland Volunteers sent them to the President with this introduction:

To His Excellency Abraham Lincoln. Will your excellency please accept the two enclosed copies of Waterford News and excuse me for taking the liberty of sending them to you… You will see by the Sending, the intention of the Fair Editresses in editing the Paper under the difficulties which they do. ‘Tis for to aid the Sanitary Commission. They have already made up nearly $1000 for the same purpose!

The last edition of the paper appeared less than a week before General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. After the war, The Waterford News was quickly forgotten. The village took years to recover from the rebellion, and many of those who had fled to the north and west – particularly Quakers – never returned. Moreover, Confederate veterans and their sympathizers soon reasserted their political predominance in Loudoun County.

After the War

Soon after the war ended, Sarah Steer applied to the Freedmen’s Bureau for the funds to open a school for the children of freedmen in Waterford. She also asked the Philadelphia Meeting and local Quakers for contributions. Sarah did not wait for the school to be finished; she began teaching from her side yard in 1865, becoming the first teacher of black children in Loudoun County. Sarah eventually married in 1904.

Lizzie and Her Lieutenants

By 1862, Lizzie had fallen in love and became engaged to a Lt. Holmes of the 7th Indiana Regiment, who was killed at Petersburg in the summer of 1864. Lt. James Dunlop of the same regiment, a friend of her fallen fiance, had written to Lizzie with news of Holmes’ death. After the war, Dunlop returned home to Indiana to marry his childhood sweetheart, but she died two years after their wedding.

In 1881, Dunlop came to Washington on business and sent a card to the Dutton home. The reply was a letter from Miss Lizzie Dutton inviting Dunlop to her home, and the two renewed their acquaintance:

…matters flowed on so easily, smoothly, and naturally, that in a few weeks Mr. Dunlop found himself at his Indiana home busily engaged in preparing for the reception of a new mistress, and soon the little town of Waterford was all a blaze of light and a scene of general rejoicing, for the lady was popular and beloved by all.

Joseph Dunlop and Lizzie Dutton were married on January 22, 1882.

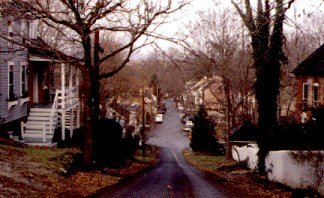

Image: Main Street in Waterford today

Image: Main Street in Waterford today

Tucked away in northern Loudoun County, Waterford retains its narrow streets and original buildings from past centuries which have been preserved for decades by the National Historic Landmark status that encompasses the entire village.

Lida and William

Through the years, a tale was passed down to their children and grandchildren about an incident that occurred during the war, of a handsome Confederate soldier approaching a pretty young girl and politely asking for directions. While it was against her principles to knowingly lie, it was against her nature to help a Confederate get where he was going any faster than he should. Instead she gave instructions based on landmarks, which only a local would understand: left at this rock, right at that post, etc.

When she stopped talking, the man quietly asked, “Miss, which side would you like for me to be on?” She blurted out: “If you’re a Rebel, I hate you; if you’re a Northerner, I love you!” Little did she know, the man was deliberately dressed like a Rebel soldier. He had become a turncoat, literally, by turning his blue cavalry jacket inside out hoping the muslin lining would pass as Confederate homespun while he spied on the enemy.

At that point, the soldier introduced himself as Lt. John William Hutchinson of the 13th New York Cavalry, and opened his jacket to show her the brass buttons and navy wool of a Union officer.

When William Hutchinson came back after the war, Lida Dutton married him. He joined the Quaker church and moved his bride north to New York. In the years to follow, William often told the story of their first meeting to their children and grandchildren. When he came to the part where she promised that she would love him if he were a Northerner, Lida would protest in her soft Virginia drawl that she had said like, not love.

William and Lida Hutchinson were married for 53 years before he passed away.

SOURCES

Three Women Journalists of the Civil War

Civil War Talk: Waterford, Virginia Underground Newspaper, Journalists

The Waterford News: A Pro-Union Newspaper Published by Three Quaker Maidens