Delaware: A Short Path to Freedom

Delaware, the northernmost slave state, may be small but it played a big part in the lives of men and women fleeing from slavery. The city of Wilmington was the last station on the Underground Railroad (UGRR). With the slave state of Maryland on one side and the free states of Pennsylvania and New Jersey on the other, Delaware offered a direct route to freedom.

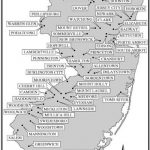

Image: Map of the United States showing routes traveled by fugitive slaves

Running the Underground Railroad

The system of aiding fugitives was established in the early 1800s, but the term Underground Railroad was not used to describe the network of secret routes and safe houses used by slaves to escape to the North until the early 1830s. Aiding them in their flight were a string of abolitionists who helped them along their way, even though such actions violated state and federal laws.

In keeping with this terminology, the homes and businesses that harbored runaways were known as depots; they were run by stationmasters. Conductors moved the fugitives from one depot to the next. Stockholders contributed money and clothing so that fugitives would not give themselves away by wearing their worn work clothes.

A trip on the Underground Railroad was fraught with danger. The slaves first had to get away from their owners, usually after dark. Sometimes a conductor, pretending to be a slave, would go to a plantation to guide the fugitives on their way. Once the fugitives reached a safe haven in the North, local abolitionists helped them find homes and jobs. Many went on to Canada, where they could not be captured by their former owners.

Being caught aiding runaways in a slave state was much more dangerous than in the North. White men received harsher punishments than white women, assuming the accused made it to court instead of perishing at the hands of an angry mob. Penalties included imprisonment or whipping. The harshest punishments – burning or hanging – were reserved for African Americans caught aiding fugitives.

Harriet Tubman

The best known conductor on the UGRR is Harriet Tubman. Though her age was never exactly determined, she was born around 1820 near Bucktown, Maryland. In 1845 she married John Tubman, a free black man who ironically did not support his wife’s desire to be free. She remained with him until 1849 when she fled from bondage on Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

Tubman then returned to the slave states nineteen times to rescue more than 300 slaves, often leading them through Wilmington, Delaware on their way North. The first trip was to Baltimore in 1850 to retrieve her sister and her sister’s children; on several subsequent trips she rescued other family members. She earned money for her rescue missions by working in Philadelphia and Cape May, New Jersey.

In a subsequent trip through Wilmington, Tubman, three of her brothers and several other slaves were hidden in a straw-covered wagon pulled by a group of bricklayers as they attempted to cross the Market Street Bridge. When they spotted slavecatchers on the other end of the bridge, the bricklayers pretended to be boisterous drunkards returning from a binge, and the slavecatchers ignored them.

Tubman’s missions entailed hundreds of miles of walking, navigating through rough terrain and dangerous waters, outwitting professional slave catchers and evading hunting dogs. The shotgun Tubman always carried was a visual threat to any who lost heart and wanted to turn back, which would result in extreme punishment or death for them all. Once she reached Delaware, she sensed the smell of freedom in the air. The exhausting trip would soon be over.

Image: Unwavering Courage in the Pursuit of Freedom Monument

Tubman-Garrett Riverfront Park

Wilmington, Delaware

Dedicated October 3, 2012

This sculpture by Mario Chiodo captures UGRR stationmaster Thomas Garrett (left, holding lantern) who provided a safe haven for runaways. In the arms of conductor Harriet Tubman (center) is an infant she has drugged so it will sleep quietly and not give away their hiding place. Traveling during winter and only at night, two exhausted fugitives (right) are slipping and sliding in the snow. The piece is nine feet high; seven feet, six inches wide; and ten feet, six inches long.

Thomas Garrett

Harriet Tubman collaborated with abolitionist Thomas Garrett of Wilmington, Delaware on at least eight of her missions. While maintaining a hardware business, Garrett acted as a key stationmaster on the Underground Railroad. Garrett helped Harriet Tubman by giving her and her fugitives food, clothing, shelter, and money. His antislavery work so angered Maryland authorities that they offered a reward of $10,000 for his arrest.

In 1848, Garrett was brought before a Federal court, where he admitted he had aided fugitive slaves and would continue to do so. The judge fined Garrett $5400, which forced him into bankruptcy. However, with the help of his abolitionist friends, he was able to re-establish his business. Garrett is credited with aiding more than 2000 fugitives escape to freedom in his forty year career as a stationmaster.

Garrett wrote of his friend Tubman and her work on the UGRR, detailing her many trips through the streams and cold weather and her long distance treks in wet clothes. One letter recounted: “Harriet, and one of the men had worn their shoes off their feet, and I gave them two dollars to help fit them out, and directed a carriage to be hired at my expense.” When Garrett died on January 25, 1871, he left instructions that he was to be carried to his grave by African Americans.

The Shadd Family

African Americans began working for abolition in the early 1800s. Abraham Shadd of Wilmington, Delaware was a descendant of a German military officer and a free black mother. Shadd married, fathered 13 children and earned a respectable living as a shoemaker, a trade he learned from his father. Shadd attended the first National Convention to protest racism in Philadelphia in September 1830, and went on to attend major meetings regarding the abolition of slavery over the next decades.

Shadd was elected president of the National Negro Convention in 1833. Along with Peter Spencer, he opposed African colonization and argued for the entitlement to civil rights he felt black Americans should have as a result of their significant investment in the country’s foundation. Shadd conducted antislavery and Underground Railroad activity from his home until his move to Canada in 1851.

Abraham’s daughter Mary Ann Shadd (1823-1893) was a female pioneer in the quest for racial and gender equality in America. Born in Wilmington, Delaware in 1823, Mary Ann became an educator, newspaper publisher, lawyer, and journalist.

Appalled by the passage of the fugitive slave act in 1850, Shadd relocated to North Buxton, Ontario. There she founded the Provincial Freeman, becoming the first black woman to publish a newspaper in North America. Along with Samuel Ringgold Ward, a runaway from Kent County, Maryland, Shadd helped fugitives find land granted by the Province to runaways.

In 1855 Shadd became the first woman to speak at the National Negro Convention and eventually testified before the U.S. Congress in favor of women’s suffrage. In 1883 she obtained a law degree from Howard University in Washington, DC and established a legal practice dedicated to obtaining equal rights for black Americans. She continued to write for newspapers and fight for equality until her death in 1893.

Lincoln’s Proposal

In November of 1861, President Abraham Lincoln proposed that the Delaware legislature pass a law to emancipate all of the state’s slaves. In return, the federal government would reimburse slaveholders $500 for each slave set free. As Lincoln expressed to Delaware slaveholder, Benjamin Burton:

If I can get Delaware to undertake this plan, I’m sure the other border states will accept it. This is the cheapest and most humane way of ending this war and saving lives.

However, Lincoln’s proposal was never brought to a vote by the legislature, and his attempt at the use of diplomacy in the struggle to liberate slaves failed. Also, slave states like Delaware, Maryland, Missouri and Kentucky that sided with the Union but remained slave-holding, the Emancipation Proclamation did not apply. For their loyalty to the Union, the slaveholders of these states were rewarded with the use of their slaves until the end of the war.

Friends’ Meetings and Safe Havens

The tiny Appoquinimink Meeting House in Odessa, Delaware is another example of the role Quakers played in the Underground Railroad. A member of the Meeting, John Hunn, owned the farm to the west. Though Hunn burned his papers before he died, Harriet Tubman is quoted as saying she hid in the Meeting House at times. The Meeting House’s second story has a removable panel leading to spaces under the eaves. It also originally had a cellar reached by a small side opening at ground level.

Delaware became the bridge to freedom for fugitives and the site of the last attempt at capture for slave hunters. After the Fugitive Slave Law passed in 1850, requiring free citizens and lawmen alike to aid in the capture of escaped slaves in the free states, Wilmington could not be seen any longer as the last stop before freedom, but an important resting point before the second leg of a very long journey to Canada.

Delaware’s waterways also served as paths to safety when followed by runaways who stealthily avoided horse-trodden roads and pedestrian paths. Rivers like the Choptank, Nanticoke and St. Jones provided cover and the means to hide one’s tracks. On the other hand, these same waterways were treacherous. Slavecatchers trolled the rivers seeking innocents to capture and sell into bondage for profit.

John Dickinson

An important figure in the American Revolution as a signer of the Constitution, Founding Father John Dickinson is one of Delaware’s most prominent historic figures, and one of the few active abolitionists. Dickinson’s plantation in Dover was one of the largest in Delaware.

At one time, he was one of the largest slave owners in the Delaware Valley, holding at least 59 men, women, and children. Yet, as he grew older and adhered more closely to the beliefs of the Quakers, he increasingly adopted their abolitionism. In An Essay of a Frame of Government for Pennsylvania (1776), he proposed a law be passed stating that “No person hereafter coming into, or born in this country, to be held in Slavery under any pretense whatever.”

In 1776 Quakers made it known that holding humans in bondage was an unacceptable practice. It was recommended strongly that all Quakers free their slaves. The county required a bond payment for each slave he set free. Because Dickinson had so many slaves, the payment would be high. However, if done gradually, the economic impact would be less. By 1786, Dickinson had freed all of his slaves, and was paying free blacks to work his farm.

Image: John Dickinson Plantation

Dover, Delaware

As president of Delaware in 1782, Dickinson urged the Assembly to insure that families not be “cruelly separated from one another, and the remainder of their lives extremely embittered.” In 1786, he wrote abolition legislation for Delaware, but it did not pass. At the 1787 U.S. Constitutional Convention, Dickinson was one of the few delegates to object to the slave trade on moral grounds and moved to have it prohibited in the Constitution. This motion resulted in Article 1, Section 9 of the Constitution:

The migration or importation of such persons as any of the states now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the year one thousand eight hundred and eight, but a tax or duty may be imposed on such importation, not exceeding ten dollars for each person.

Legacy

All along the trail of the Underground Railroad in Delaware, there remain signs of those who secretly passed through here. Historic homes, barns, and paths barely visible, remain as a testament to the courage of those who escaped and those who helped them on their way. Although many landmarks have not survived in the years since the UGRR operated, museums and historical organizations continue to collect and display evidence from this time in history.

SOURCES

History Net: Underground Railroad

Whispers of Angels: Thomas Garrett

Thomas Garrett, A Dedicated Abolitionist

Delaware Stops Along the Underground Railroad