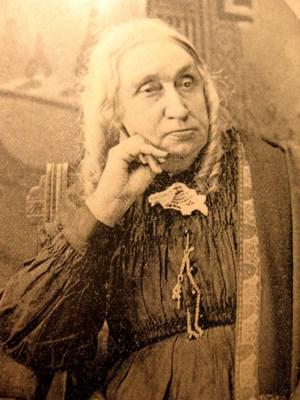

Educator, Writer and Freethinker

Lucy Colman was an educator, writer and prolific social reformer who was actively involved in the abolitionist, women’s suffrage and Freethought movements. She also worked for racial justice and for the education of African Americans, accompanied Sojourner Truth on a visit to President Abraham Lincoln.

Early Years

Lucy Newhall Danforth was born July 26, 1817 in Sturbridge, Massachusetts, a descendant of John and Priscilla Alden [link] on her mother’s side. In her autobiography, she reported that from an early age, about six, she was horrified to learn of the existence of slavery, and bothered her mother with many questions about it. In 1824, Lucy’s mother died, and her mother’s sister Lois took over mothering tasks. Lois married Lucy’s father in 1833.

Marriage and Family

In 1835, Lucy Danforth married a fellow Universalist John Maubry Davis, and they moved to Boston. They had no children. Davis died of consumption in 1841. Though she was never formally educated, Lucy had worked as a schoolteacher as a young woman. She now returned to teaching to support herself.

In 1843, Lucy married Luther Coleman (she later changed the spelling of her married name to Colman). They moved to Rochester, New York. About 1845, their daughter Gertrude was born. Motherhood brought Colman’s attention to the issue of women’s rights. She began to ask why married women and mothers had so few rights, and why women were dependent on the goodwill of their husbands for what freedoms they had.

The National Women’s Rights Convention was an annual series of meetings that increased the visibility of the early women’s rights movement in the United States. The first national meeting was held in 1850 in Worcester, Massachusetts, and Lucy Colman is listed among those who attended. Speakers discussed equal wages, expanded education and career opportunities, women’s property rights, marriage reform and temperance.

Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis was chosen president of the first national convention. Other women speakers included Harriot Kezia Hunt, Ernestine Rose, Antoinette Brown Blackwell, Abby Kelley, and Lucretia Mott. In the early 1850s, Colman also began her involvement with the anti-slavery movement, and at the urging of her friend, Amy Kirby Post, Colman began making speeches on that topic. By 1852 she had renounced Christianity. She later wrote:

I had given up the church, more because of its complicity with slavery than from a full understanding of the foolishness of its creeds.”

Andrew Jackson Davis, a leader in the Spiritualist movement, was staying with the family when Luther Colman was killed in 1854 while working at the New York Central Railroad. Lucy Colman credited the accident to the unwillingness of the company to spend money for needed repairs. Andrew Jackson Davis performed the funeral service, which was held at Corinthian Hall.

After the funeral, Lucy Colman went to the railroad company to ask what support she could expect from then, having been widowed as a result of a work accident. While the company had paid for the funeral, and some officials of the company had attended the service, the company told her that she would not get anything from them.

Career in Education

Left to earn a living for herself and her daughter after her second husband was killed in 1854, Colman accepted employment as a teacher in a segregated “colored school.” There, she met Susan B. Anthony, who arranged for Colman to speak at the state teachers’ convention; she gave a controversial speech against corporal punishment in schools. Both women spoke out against the unequal salary of male and female teachers.

Colman became so disgusted with the school’s segregation that she lobbied parents to withdraw their children, causing the school to close and losing her job in the process. By 1856, Rochester was providing education for both white and black children.

Anti-Slavery Work

Lucy Colman became an abolitionist lecturer, sacrificing security, comfort and wages to work against slavery. From 1856 to 1860, she worked first with the Western Anti-Slavery Society and then with the American Anti-Slavery Society. She lectured against slavery in the midwestern states of Ohio, Iowa and Michigan, and her writings occasionally appeared in the anti-slavery newspaper, The Liberator.

She found at many of her appearances that local ministers led the opposition against her. She established a reputation as a campaigner for liberal causes whose special gift lay in silencing Christian hecklers by throwing their own principles back at them. When one minister quoted the Bible’s prohibitions of women teaching, she quoted back at him the Bible’s prohibition against men being clean-shaven.

In 1858, during a time she was in Rochester, she joined in a major protest against capital punishment led by Frederick Douglass and Susan B. Anthony. In 1859, she helped in a petition drive for the right to vote for women in New York State.

Life During the Civil War

In November 1862, Lucy Colman’s teenage daughter Gertrude was attending the New England Female Medical College when she died. Rather than a religious service, Colman chose to have Frederick Douglass officiate.

Lucy found an autograph book that had been compiled by her daughter Gertrude and continued to collect signatures. The book contains seventy-six autographs of people, often with abolitionist or Union sentiments, dated almost entirely in the 1860s, either in Washington, DC (where Lucy worked during the war) or Rochester (her longtime home).

The signatures suggest the wide-ranging impact of the abolitionist movement, the significance of women within the movement and the close ties between abolitionist and women’s rights leaders. Among the signatories are such notables as William Wells Brown [link], Ottilie Assing, General Oliver O. Howard, Parker Pillsbury, President Andrew Johnson, Wendell Phillips, President Abraham Lincoln and Jane Grey Swisshelm.

In May 1863, Colman was one of the secretaries at the Women’s National Loyal League, which was formed to campaign for an amendment to the U.S. Constitution to abolish slavery. In the largest petition drive in the nation’s history up to that time, the League collected nearly 400,000 signatures and presented them to Congress. Its petition drive significantly assisted the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, which ended slavery in the United States.

Lucy Stone presided at a convention of the League, along with Ernestine Rose, Antoinette Brown Blackwell, Amy Post and Angelina Grimke. They called on women to “do everything in their power to aid the Government in the prosecution of this war to the glorious end of freedom.” Resolutions supported the Emancipation Proclamation and legal freedom for former slaves with no laws that would “debar them from any rights or privileges as free and equal citizens of a common Republic.”

In 1864, Colman took on a position as matron at the National Orphan Asylum in Washington, DC, run by the National Association for the Relief of Destitute Colored Women and Children. In 1864 and 1865, she taught and served as a superintendent in schools in Washington and Arlington, Virginia, for the National Freedman’s Relief Association, an institution founded to help former slaves.

Truth and Lincoln

On October 29, 1864, Lucy Colman accompanied Sojourner Truth to the White House to meet President Abraham Lincoln; she is the Mrs. C whom Truth referred to in a letter about the visit. Colman had arranged the meeting via Elizabeth Keckley, dressmaker and confidante of Mary Todd Lincoln.

Colman was not impressed by the president’s reception of the former slave. This quote was written long after the events in her memoirs Reminiscences, and its veracity has been questioned:

Mr. Lincoln was not himself with this colored woman. He had no funny story for her, he called her Aunty, as he would his washer-woman, and when she complimented him as the first Antislavery President, he said, “I am not an Abolitionist; I would not free the slaves if I could save the Union in any other way. I am obliged to do it.”

About 1870, Colman moved in with her sister, Aurelia Raymond, a physician in Syracuse, New York.

Freethought Movement

During this time, Colman wholeheartedly embraced freethought, a philosophical viewpoint that opinions or beliefs should be based on science, logic and reason, and should not be derived from religion, authority, government or dogma. With this movement came a devoted group of freethinkers.

A freethinker is a person who rejects accepted opinions, especially those concerning religion; one who forms his or her own opinions about important subjects instead of accepting the beliefs of others. Opinions are formed on the basis of an understanding and rejection of tradition, authority or established belief. To be a freethinker, one has to be willing to consider any idea and any possibility.

Lucy Colman lectured widely, contributed to every reform cause of her day, and touched the lives of the time’s most noteworthy freethought activists. Colman was quite active in freethought circles, writing columns for The Truth Seeker, a freethought journal and speaking often at conventions.

She attended the 1878 New York State Freethinkers’ Association Convention in Watkins Glen, New York, at which D. M. Bennett, Josephine Tilton and W.S. Bell were arrested for selling a marriage reform and birth control pamphlet. Colman arranged bail for Tilton and campaigned successfully for charges to be dropped against all three. She spoke at the New York Freethinkers’ Association convention at Hornellsville in September 1880.

In 1878, at a convention of the National Woman’s Suffrage Association, Colman proposed a resolution denouncing religion as the major source of women’s inferior position in society. Frederick Douglass argued against the resolution, but Colman responded with his own arguments about equality. The resolution passed.

Excerpt from Lucy Colman paper published in The Truth Seeker, March 5, 1887:

If your Bible is an argument for the degradation of woman, and the abuse by whipping of little children, I advise you to put it away, and use your common sense instead.

In 1889, her friend and mentor Amy Post died. Colman spoke at her funeral, held at the Unitarian Society.

Colman contributed regularly to leading freethought publications, The Truthseeker and Boston Investigator, and over a period of several years, she wrote her memoirs, Reminisences in the Life of a Reformer of Fifty Years, published in 1891.

In writing of Colman for 400 Years of Freethought in 1898, Samuel Porter Putnam describes her among the New World roll of honor: “Lucy N. Colman, in whom the ardor of youth finds no ashes in snowy age, and the silver morn is radiant ever.” He listed her along with Sarah Bush Lincoln (Abraham Lincoln’s stepmother), the Grimke sisters, Matilda Joslyn Gage and Helen H. Gardener.

In a brief biography of Colman for the book, Putnam described her:

Mrs. Colman is radical in every direction. She is opposed to white slavery as well as black slavery, and has devoted herself to woman’s rights as well as to the rights of man. She is a radical Freethinker, having outgrown superstitions of every kind. She has not lost her interest in any living question. She has had a busy and eventful career; has mingled with the world, among its characters and great movements, and has done her share to bring about the great gains of the present time. She has shown what a woman can do who has self-reliance, energy, and devotion to truth and right. Her name shines in the annals of progress.

Lucy Colman died January 18, 1906, at age eighty-eight.

SOURCES

About.com: Lucy N. Colman

The Freethought Trail: Lucy N. Colman

Freedom From Religion Foundation: Lucy Colman