Feminists and Activists for Women’s Equal Rights

Image: Executive Committee of the National Woman Suffrage Association (1869)

Women fought for more than 200 years to obtain the rights that were guaranteed to men in the U.S. Constitution. When the nineteenth century began, a woman was not permitted to vote or hold office; she had few rights to her own property or earnings; she could not take custody of her children if she divorced; she did not have access to a higher education.

Birth of Feminism

In the 1830s, thousands of women were involved in the movement to abolish slavery. While working to secure freedom for African Americans, these women began to see legal similarities between their situation and that of enslaved black men and women. Out of the abolitionist movement, feminism was born, and many women involved in the early abolitionist movement went on to become important leaders in the early women’s rights and suffrage movements.

Women like Angelina Grimke and her sister Sarah Grimke became famous for making speeches about abolition to audiences of males and females, which were called promiscuous audiences. For this radical action, clergymen soundly condemned them. As a result, in addition to working for abolition, the Grimke sisters began to advocate for women’s rights; other women followed their lead.

The feminist movement demanded equal political, economic, and social rights for all women regardless of their ethnic background; it was the leading force behind the women’s rights movement. The first wave of feminism began with the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, and it continued on throughout the last half of the 19th century and the first two decades of the 20th century, until women won the vote in 1920.

This excerpt from the article “The Roots of Individualist Feminism in 19th-Century America” explains the differences within the movement:

[There are] two opposing traditions within feminism: individualism and socialism. Both believe that women should have the same rights as men, that women should be equal, but the meaning of equality differs within the feminist movement. Throughout most of its history, American mainstream feminism considered equality to mean equal treatment under existing laws and equal representation within existing institutions. The focus was not to change the status quo in a basic sense, but rather to be included within it.

The more radical feminists protested that the existing laws and institutions were the source of injustice and, thus, could not be reformed. These feminists saw something fundamentally wrong with society beyond discrimination against women, and their concepts of equality reflected this. To the individualist, equality was a political term referring to the protection of individual rights; that is, protection of the moral jurisdiction every human being has over his or her own body… Women could be equal only after private property and the family relationships it encouraged were eliminated.

Feminist Movement

The women’s rights movement, also called the feminist movement, was established to combat sexual discrimination and to gain opportunities for women equal to those of men. It began at the First Women’s Rights Convention at Seneca Falls, New York in July 1848, the first meeting on women’s rights ever held in the United States.

For the occasion, Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote the Declaration of Sentiments, which called for complete political, economic and social equality with men, including educational opportunities, equal pay, and the right to vote. Its language deliberately quoted the Declaration of Independence – illustrating how the men who wrote and approved that document had ignored half the population of the United States.

Women’s Rights After the Civil War

The women’s rights movement had been gathering a following before the war, and it resumed after the war’s conclusion. Although the majority of women were forced to return to their traditional domestic roles, this period marked a significant turning point in women’s history. Women were getting recognition, as when President Andrew Johnson wrote a letter praising Union spy Sarah Thompson, calling her a woman of the highest respectability.

The image of female empowerment in wartime brought the movement new energy. The war had given women a chance to control their own lives, to earn their own money, to manage their own finances, to be independent. Some women were no longer willing to complacently fill the roles they had occupied before the war.

Some women had entered paid employment in government service, industry and public schools in significantly greater numbers than previously. The 1870 Census Report listed “Females Engaged in Each Occupation” for the first time. In 1890 the Census Bureau began to separate out data for married, single, divorced and widowed women.

Women’s Suffrage Movement

Soon after the Civil War the women’s suffrage movement began to gather momentum. Susan B. Anthony focused her efforts on fighting for political rights for women, arguing that until women had the right to vote, they would have no other. In January 1868, Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton began publishing The Revolution, a paper that supported suffrage for women.

In November 1868, the largest women’s rights convention ever held in the United States to date met in Boston. Lucy Stone, her husband Henry Browne Blackwell, Isabella Beecher Hooker and Julia Ward Howe founded the New England Woman Suffrage Association (NEWSA) for the sole purpose of gaining the vote for women.

In November 1868, the largest women’s rights convention ever held in the United States to date met in Boston. Lucy Stone, her husband Henry Browne Blackwell, Isabella Beecher Hooker and Julia Ward Howe founded the New England Woman Suffrage Association (NEWSA) for the sole purpose of gaining the vote for women.

Image: Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Leaders of the Women’s Rights Movement

Over the next few decades, women’s suffrage became the focus of the women’s rights movement. On May 15, 1869, Anthony and Stanton founded the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) to secure an amendment to the Constitution in favor of women’s suffrage. They continued work on The Revolution which included radical feminist challenges to traditional female roles. Radical feminism aimed to challenge and overthrow patriarchy by opposing standard gender roles.

In 1887, after 20 years of working in parallel toward the same goals, Stone called for a merger of the various suffrage organizations. In 1890, the two groups united to form one national organization known as the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), and suffragists began working together toward the same goal.

The NAWSA became the mainstream pro-suffrage group. It represented millions of women and was the parent organization of hundreds of smaller local and state groups. NAWSA’s strategy was to push for suffrage at the state level, believing that state-by-state support would eventually force the federal government to pass the amendment. The NAWSA hosted theatrical suffrage parades, and held annual conventions that helped to keep its members energized.

Equality, She Wrote

In the 1820s, one publisher stated that “the utmost limits to which the sale of a popular book can be published” would be 6,500. In 1850, Susan Warner’s The Wide, Wide World shattered that prediction, becoming the first novel to reach the one million mark in sales. In 1852, Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe opened the eyes of the American public to the evils of slavery; it sold over 50,000 copies in the first two months.

Women authors had come into their own, as both an economic and social force. Angered by what she learned about the U.S. government’s treatment of Native Americans, Helen Hunt Jackson researched and wrote a nonfiction account entitled A Century of Dishonor (1881), and mailed a copy to every United States senator.

When she received no response, Jackson wrote Ramona (1884), a novel centered on the love story of a Native American man and a young mixed-blood woman. Through the tragic experience of Ramona and her love, Jackson awakened the conscience of the American public. Like Stowe, Jackson used melodrama to arouse public opinion.

In 1892, Charlotte Perkins Gilman wrote a novella, The Yellow Wallpaper, based upon her own experience with 19th century cures for depression among women. Forbidden by her husband/doctor to read or write, Gilman’s unnamed narrator goes insane. Her horrifying journey is recounted through the journal she writes in secret. Gilman wrote:

To define individual duty is difficult; but the collective duty of a class or sex is clear. It is the duty of women… to bring children into the world who are superior to their parents; and to forward the progress of the race.

In the 1860 essay collection, Historical Pictures Retouched, Caroline Dall called Margaret Fuller’s book Woman in the Nineteenth Century “doubtless the most brilliant, complete, and scholarly statement ever made on the subject.” Typically harsh literary critic Edgar Allan Poe called Fuller’s work “a book which few women in the country could have written, and no woman in the country would have published, with the exception of Miss Fuller.” Other early feminist writers include Eliza Farnham and Frances Dana Gage.

Higher Education

Women did not have access to higher education before 1848. While a few women might attend a female seminary, they were not allowed into colleges and universities. One of the complaints documented at Seneca Falls in the Declaration of Sentiments was the lack of higher education available for women. What the signers of that document wanted was access to coeducation, where women would be taught the same courses as men, not a separate and unequal education. This was a radical approach at that time.

The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward women, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her… He had denied her the facilities of a thorough education, all colleges being closed against her.

Women did begin to go to college after the Civil War, and for the most part they went to coeducational institutions. Newly established midwestern land grant colleges opened as coeducational facilities, but established schools in the northeast resisted the change. In 1870 only 0.7% of the female population went to college. This percentage rose slowly, by 1900 the rate was 2.8% and it was only 7.6% by 1920.

Those pioneering women who did seek a college degree faced many critics, some of the harshest from the medical profession. Harvard Medical School professor Dr. Edward Clarke asserted in his widely respected Sex and Education (1873) that intellectual work damaged women’s reproductive organs. This scientific reasoning added fuel to the arguments of those who did not want women to go to college for social reasons:

A girl could study and learn, but she could not do all this and retain uninjured health, and a future secure from neuralgia, uterine disease, hysteria, and other derangements of the nervous system.

In 1885 historian Henry Adams complained bitterly in a letter of protest to the American Historical Association when he found a woman historian listed in the program of an upcoming AHA meeting. (His wife Clover Adams committed suicide by swallowing potassium cyanide on December 6, 1885, at age 42.) Henry Adams wrote this about educated and ambitious women:

Our young women are haunted by the idea that they ought to read, to draw, or to labor in some way, not for any such frivolous object as making themselves agreeable to society… but “to improve their minds.” They are utterly unconscious of the pathetic impossibility of improving those poor little hard, thin, wiry, one-stringed instruments which they call their minds, and which haven’t range enough to master one big emotion much less to express it in words or figures.

Faced with these negative opinions, early college women felt the need to prove that college life would not injure their health. In 1885 the Association of Collegiate Alumnae published a study:

In conclusion, it is sufficient to say that the female graduates of our colleges and universities do not seem to show, as the result of their college studies and duties, any marked difference in general health from the average health… of women generally…

However, there was a genuine fear that higher education would make a woman unfit for marriage and motherhood. And in fact, 50-60% of the first generation of college women never married, or waited until they were considerably older before they wed. When faced with the option to work or to marry, many women decided to work, turning their energies to social reform and establishing their own careers.

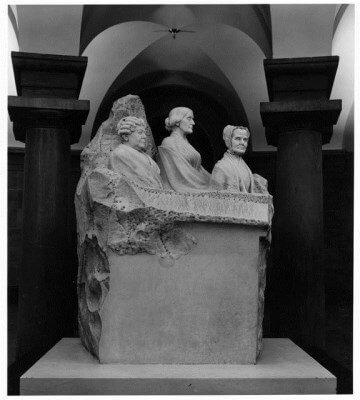

Image: Triumvirate of Women Leaders

Image: Triumvirate of Women Leaders

Statue by Adelaide Johnson

Stanton, Anthony and Mott

U.S. Capitol Building

Washington, DC

A majority of college women surveyed reported improved health as a result of their exposure to sports and exercise. Women’s basketball was a booming sport in the late 1890s on college campuses, as was women’s participation in tennis, volleyball, tetherball and bicycling. Like many other demands of the Declaration of Sentiments, opening the doors of higher education happened much sooner than the right to vote.

SOURCES

Women’s Rights in the 19th Century

Women writing in 19th Century America

Wikipedia: Women’s Suffrage in the United States

The Roots of Individualist Feminism in 19th-Century America