Romantic Legends of the Civil War

Arabella Griffith married Francis Barlow the day after he enlisted in the Union Army. Francis was a well-established New York lawyer, while Arabella was 10 years his senior and a member of New York high society. The following year she joined him in service to the Union Army.

Arabella Griffith married Francis Barlow the day after he enlisted in the Union Army. Francis was a well-established New York lawyer, while Arabella was 10 years his senior and a member of New York high society. The following year she joined him in service to the Union Army.

Image: Arabella Griffith Barlow

Arabella Wharton Griffith was a young woman of twenty-two years when she moved from rural New Jersey to New York City to work as a governess, a bold move for a woman of that time. Her vibrant personality soon caught the attention of a group of literary-minded socialites, artists and politicians. Diarist George Templeton Strong wrote that she was, “certainly the most brilliant, cultivated, easy graceful, effective talker of womankind, and has read, thought and observed much and well.”

Francis Channing Barlow was born on October 19, 1834, in Brooklyn, New York. After his father, a Unitarian Minister, abandoned his family in 1838, his mother Almira moved Francis and his two brothers to the Utopian community of Brook Farm in West Roxbury, Massachusetts. Almira wanted her sons to continue their education with the Farm’s leader, George Ripley.

It has been said that the men at Brook Farm paid a little too much attention to Barlow’s very attractive mother, and they left Brook Farm in 1844. After graduating at the top of his class from Harvard in 1855, Frank, as he was called by friends and family, studied law. Barlow then moved to New York City, where he was admitted to the New York State Bar in 1858. He practiced law there with George Bliss until the outbreak of war.

Shortly before the Civil War in 1861, Arabella Griffith met Frank Barlow. Arabella was a decade older than Frank, as his friends called him, but the age difference did not seem to matter. The couple married on April 20, 1861, the same day that Barlow answered President Abraham Lincoln‘s call for volunteers by enlisting in the Union Army. He had absolutely no prior military education or experience.

In the Service of the Union

Arabella’s friend George Templeton Strong was one of the founders of the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC), which was organized in 1861 to promote cleanliness and sanitation in the Union army camps and to care for the sick and wounded in field hospitals. In the summer of 1862, Arabella joined the Commission and devoted her life to caring for sick and wounded Union soldiers, occasionally meeting with her husband when time permitted.

The day after he and Arabella were married, Frank sailed for Fortress Monroe to defend the federal capital at Washington, DC. He then served with General Robert Patterson in the Shenandoah Valley, and during the Peninsula Campaign under General George B. McClellan. Barlow’s bravery and leadership qualities did not go unnoticed. He received several promotions in quick succession. On April 14, 1862, he was promoted to a full colonel.

The next year Arabella followed Frank into service, volunteering as a nurse in the United States Sanitary Commission. On the bloodiest single day of the war, September 17, 1862, at Antietam, Barlow received wounds to his face from an artillery fragment and in the groin from grapeshot. Arabella was in Baltimore when she learned that Frank was with the army in Maryland. She arrived at Antietam on the day of the battle, and nursed his wounds, first in a military hospital, and then in a private room she had arranged, but it took him seven months to fully recover.

Because of his performance at Antietam, Barlow was promoted to brigadier general. He returned to service on April 17, 1863, just in time for the major battles of that year. At the Battle of Chancellorsville, he commanded a XI Corps brigade in General Daniel Sickles‘ III Corps. It was the only brigade that was not annihilated by Jackson’s famous surprise flank attack, and Barlow survived this battle without injury.

On July 1, 1863, the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg, he commanded a division of Howard’s XI Corps on the extreme right of the Federal line, north of the town. He led his men to a defensive position on a slight rise in the terrain known locally as Blocher’s Knoll (later renamed Barlow’s Knoll), which was too far in front of the other XI Corps division commanded by General Carl Schurz.

Therefore, Barlow’s position formed a salient that could be attacked from multiple sides. CSA General Jubal Early’s Division of Lt. General Richard Ewell‘s Second Corps arrived on the scene. About 3 o’clock, Early’s men, with General John B. Gordon‘s Brigade leading the way, hit Barlow on both front and flank. Barlow’s brigades broke under the onslaught and fell back among General Adelbert Ames‘ brigade, throwing it into confusion as well.

Barlow described what happened to him on Blocher’s Knoll in a letter home:

Finding that they [the men in his command] were going, I started to get ahead of them to try to rally them and form another line in the rear. Before I could turn my horse I was shot in the left side about half way between the arm pit and the head of the thigh bone. I dismounted and tried to walk off the field. Everybody was then running to the rear and the enemy were approaching rapidly. One man took hold of one shoulder and another the other side to help me. One of them was soon shot and fell. I then got a spent ball in my back which has made quite a bruise. Soon I got too faint to go any further and lay down. I lay in the midst of the fire some five minutes as the enemy were firing at our running men. I did not expect to get out alive. A ball went through my hat as I lay on the ground and another just grazed the forefinger of my right hand.”

Gordon and Barlow at Gettysburg

What happened to General Barlow in the next hour as his division fled and the Confederates came upon him became the subject of one of the great romantic legends of the Civil War. CSA General John Brown Gordon was on horseback nearby, and he saw Barlow fall. After the remaining Union troops retreated in disorder, leaving many dead and wounded on the field, Gordon rode up and saw Barlow lying on the ground.

Images: General Francis Barlow and General John Brown Gordon

Images: General Francis Barlow and General John Brown Gordon

The first version of the story, which probably originated with General Gordon, was published in a Georgia newspaper by 1879. The tale began as Barlow’s division withdrew toward Culp’s Hill, and then Gordon rode forward and saw Barlow lying on the ground badly wounded. Gordon stopped and gave Barlow a drink from his canteen. Over time, the account was extended, with lengthy dialogue and added detail.

Barlow told Gordon that his wife was somewhere on or near the battlefield, working as a nurse with the Union Army, and asked Gordon if he would get word to her that he had been wounded. Gordon replied that he would do so, and then directed that Barlow be carried to the shade of a tree in the rear, whom he thought would not survive for very long.

Years later, the tale came full circle with the unexpected meeting of the two former opponents at a dinner party in 1879. Upon being introduced to each other, they clasped hands and expressed surprise that they were both still alive. Thus began a friendship that would endure until Barlow’s death in 1896. The Gordon-Barlow story appealed to late Victorian sentimentality and the prevailing desire to heal the wounds of the war.

Deciphering the Legend

It is difficult to decide which version of Barlow’s meeting with Gordon at Gettysburg to believe, and it is equally puzzling as to why Barlow never set the record straight. Did he enjoy the publicity? In his article General Barlow and General Gordon Meet on Blocher’s Knoll, which appeared in the March 2004 issue of America’s Civil War magazine, Barlow’s biographer Richard F. Welch wrote:

Unfortunately, Francis Barlow never made any public comment about his connection with Gordon at Gettysburg. In the absence of any surviving statement by Barlow, there will always be an element of uncertainty regarding the events on Barlow’s Knoll. From what is known, or can be deduced, the most likely scenario is that Gordon and Barlow had a shared experience during the fighting on July 1, 1863. Gordon paused and spoke to the badly wounded enemy general on the battlefield and probably directed that he be taken off the battlefield and out of danger. He also likely played a role in getting word of Barlow’s wounding to his wife.

On the other hand, the story took on a life of its own. This was largely due to Gordon, who made the meeting at Barlow’s Knoll a key part of his popular speech “The Last Days of the Confederacy,” which he gave on numerous occasions. He also included a somewhat shortened account in his 1903 memoirs. In the swirl of battle, with one man apparently mortally wounded and the other trying to press an attack, it is unlikely that the two men engaged in the lengthy, genteel conversation that Gordon later related. Barlow may have accepted such exaggerations as insignificant annoyances to be borne in the cause of national reconciliation. Silence in the face of complete falsehoods involving his name and reputation, however, would have been alien to his character.

Arabella Saves Frank… Again

The heartwarming story of how they were reunited made Arabella and Frank Barlow one of the most celebrated couples of 1860s America. Back on that day at Gettysburg, General Gordon had succeeded in getting word to the Army of the Potomac that Barlow was badly wounded and asked that his wife be informed. When the news reached her, Arabella immediately set out to cross into Confederate-occupied Gettysburg.

Exactly how she managed to enter the village is unclear, but Gettysburg civilians reported seeing her on horseback as she was being escorted by Confederate soldiers escorted her through town and eventually to the side of her seriously wounded husband. Both Confederate and Union surgeons had declared Barlow’s wound fatal, but under her care, he soon began improve.

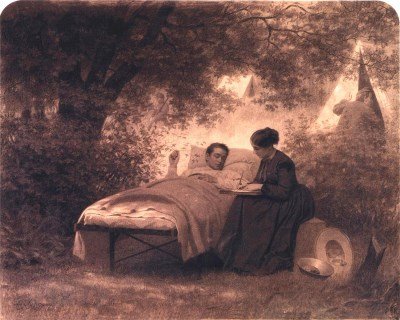

Image: The Field Hospital By Eastman Johnson

Image: The Field Hospital By Eastman Johnson

Arabella took Frank to her hometown of Somerville, New Jersey to recuperate. She also saw to it that General Barlow did not fall from the public eye, and organized as much social life as his condition would bear. In autumn, the couple visited Boston, where they stayed with Julia Ward Howe, author of the Battle Hymn of the Republic; they later went to New York, where they caught up with the friends they had made there before the war.

General Barlow returned to the Army of the Potomac in time for Ulysses S. Grant‘s 1864 Overland Campaign against Robert E. Lee in Virginia. In command of the First Division, II Corps, he was soon immersed in the bloodiest fighting of the war. His division, 8,000 strong, spearheaded Grant’s drive on Richmond. Arabella went back to her work with the Sanitary Commission.

While her husband and the federal forces dueled with Lee during the Overland Campaign (May-June 1864), Arabella was a few miles away at Fredericksburg. The small river town acted as the receiving station for the wounded from those battles. Arabella somehow gained possession of a pony and a small farmer’s wagon, with which she was continually on the move.

Nicknamed the Raider, Arabella scoured town and the country in search of provisions or other articles needed for the sick and wounded, strengthening her reputation for dedication and resourcefulness. Though Frank was seldom more than 10 miles away, with casualties pouring in from the Wilderness, Spotsylvania and the North Anna River, visits were impossible, though they managed to trade messages via ambulance drivers.

In early June, Arabella moved her base of operations to White House Landing near Port Royal, where a new hospital was being set up. Frank visited her there on June 8. Repulsed by Lee at Cold Harbor, Grant then sent the Army of the Potomac across the James River toward Petersburg, the railroad juncture that supplied the city of Richmond. Grant failed to take the city, resulting in a nine-month siege punctuated by vicious battles.

City Point, Virginia was a small waterfront landing until General Grant turned it into a new medical center for the Army of the Potomac, and Arabella contributed her nursing skills there. She was distributing food and drink to the wounded at General Barlow’s First Division hospital by June 18.

Losing Arabella

The hot, humid weather of the Virginia Tidewater made Arabella ill, but she continued to work until she collapsed. She went to Washington and friends cared for her but did not remain there for long. She returned to the front lines to see Frank, and they spent some time together at his division headquarters.

But Barlow soon grew worried that she was exhibiting the early signs of typhus, a common killer that she most likely caught while caring for the sick and wounded in the Virginia low country. Unable to leave his command, Frank sent her off with an escort to City Point and then she returned to Washington.

Arabella was feeling better for a while, but she died in Washington on July 27, 1864. Despite heavy fighting, Frank was given 15 days leave to bury her. He was crushed with grief for the loss of his wife and best friend. Arabella Griffith Barlow was buried in Old Raritan Cemetery in Somerville, New Jersey on July 31.

Dr. W.H. Reed, one of her associates at City Point, wrote this about Arabella Griffith Barlow:

Her exhausting work at Fredericksburg, where the largest powers of administration were displayed, left but a small measure of vitality with which to encounter the severe exposure of the poisoned swamps of the Pamunkey, and the malarious districts of City Point. Here, in the open field, she toiled… under the scorching sun, with no shelter from the pouring rains, and with no thought but for those who were suffering and dying all around her.

On the battlefield of Petersburg, hardly out of range of the enemy, and at night witnessing the blazing lines of fire from right to left, among the wounded, with her sympathies and powers of both mind and body strained to the last degree, neither conscious that she was working beyond her strength, nor realizing the extreme exhaustion of her system, she fainted at her work and found, only when it was too late, that the raging fever was wasting her life away.

It was strength of will which sustained her in this intense activity, when her poor, tired body was trying to assert its own right to repose. Yet to the last, her sparkling wit, her brilliant intellect, her unfailing good humor, lighted up our moments of rest and recreation. So many memories of her beautiful constancy and self-sacrifice, of her bright and genial companionship, of her rich and glowing sympathies, of her warm and loving nature, come back to me, that I feel how inadequate any tribute I could pay her worth.

Barlow was brevetted to the rank of major general on August 1, 1864, but his heart was no longer in it. He returned to the front to fight in the Deep Bottom Campaign until August 18, when he simply handed his division over to Nelson Miles and sought refuge in a military hospital at City Point. Five days later he returned to the front, but had to be carried off on a stretcher.

General Hancock’s adjutant said that during this period “he [Barlow] had been more like a dead than a living man.” The stress of military life and the loss of Arabella were too much for him, so he took an extended leave and went to Europe. Barlow returned home in March 1865, but he did not rejoin the army until April 6, 1865, just in time for Appomattox. He resigned his commission as major general on November 16, 1865.

After the war, Barlow resumed his successful law practice with his old partner George Bliss in New York City. The former general became active in Republican politics, and held a series of governmental offices.

In 1867, Barlow married Ellen Shaw, and they had three children. Ellen was the sister of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, who lost his life, but gained immortality, while leading the 54th Massachusetts Regiment of U.S. Colored Troops at the ill-fated assault on Fort Wagner in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina on July 18, 1863.

Barlow was one of the founders of The American Bar Association. He also investigated irregularities in the 1876 presidential election between Rutherford B. Hayes [link] and Samuel Tilden. He was twice elected Secretary of State of New York and was appointed United States Marshal for the Southern District of New York by President Grant.

The memory of Arabella was with him until the end. Francis Channing Barlow died January 11, 1896 from complications of the grippe (influenza) at age 62. He is buried in Brookline, Massachusetts in the Walnut Street Cemetery.

Francis Barlow died January 11, 1896 from complications of the grippe (influenza). He was 62. He is buried in Brookline, Massachusetts in the Walnut Street Cemetery.

SOURCES

New York Times: A Civil War Love Story

Romances of Gettysburg – The Barlow-Gordon Incident

General Barlow and General Gordon Meet on Blocher’s Knoll

Cleveland Civil War Roundtable by John C. Fazio: Francis and Arabella – A Love Story