Leader in the Integration of Philadelphia Streetcars

An undertaker’s daughter, Caroline Le Count outscored all the boys in her class, struck up a correspondence with a Union army general, became only the second black woman named principal of a Philadelphia public school, and put her body on the line in the battle to integrate the streetcars. Soon she was noticed on the arm of a fellow activist, Octavius Catto.

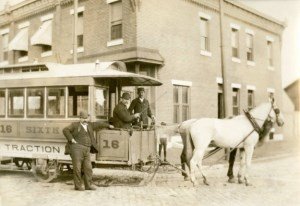

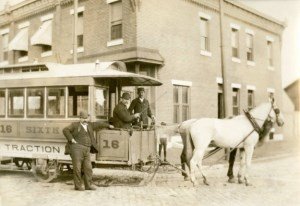

Image: The streetcar shown here at Sixth and Jackson Street demonstrates how streetcars typically operated with two horses, a driver and a conductor.

Image: The streetcar shown here at Sixth and Jackson Street demonstrates how streetcars typically operated with two horses, a driver and a conductor.

The first horse-drawn streetcars in Philadelphia began operating January 20, 1858. They moved along a set of steel rails, which provided a smoother ride at faster speeds, regardless of road conditions. The routes pioneered by the first form of on-street public transportation, the omnibus, quickly became railways. Streetcar fares were also cheaper, but still too expensive for members of the working class to use on a daily basis.

Desegregating the Cars

Horse-drawn streetcars allowed the middle class to travel freely throughout the city, but blacks were not permitted to ride on the cars. Those who attempted to ride were refused service and forcibly removed from the car. African American women like educator and school principal Caroline Le Count worked against this policy by repeatedly attempting to ride streetcars and filing petitions against the segregation law in local court.

It is highly likely that Caroline Le Count met Octavius Catto during their work as activists for African American rights. Soon they were seen together at the same functions, when their schedules permitted. A teacher at Philadelphia’s Institute for Colored Youth and a member of the Equal Rights League, Catto was involved in many aspects of the black community and enjoyed the respect of its members.

Octavius Catto was born free from slavery on February 22, 1839 in South Carolina. His family moved to Philadelphia when he was five years old, as his father became the minister of the First African Presbyterian Church. He attended a number of segregated public schools, and briefly attended an all-white middle school in Allentown, New Jersey.

In 1858, Catto was the fourth student to graduate from the The Institute for Colored Youth, a prominent center for the African American intellectual community in greater Philadelphia. Within a year he became a teacher at the Institute. Catto used his position to become deeply involved in the African American community, realizing the role that education would play in achieving equality.

Once the Civil War started, Caroline Le Count and other African American women in Philadelphia began to push for ridership on streetcars and at transportation terminals with increased frequency, arguing that streetcar rides were essential to visit African American soldiers in hospitals and camps outside the city. Octavius Catto became one of the lead participants in changing the segregated policy of Philadelphia’s streetcars.

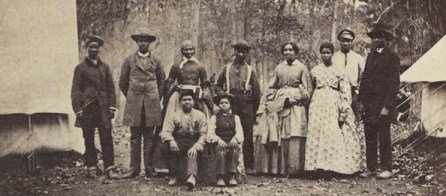

During the War, Catto helped organize eleven regiments of the United States Colored Troops (USCT), and was elevated to the rank of Major. Many of the women who confronted segregation orders on the cars were involved in wartime relief work that focused on supplying and caring for soldiers of the USCT. Many of those men now lay wounded in hospitals far from African American neighborhoods – like Camp William Penn, located more than thirteen miles north of the city.

After the War, Octavius Catto became involved in civil rights on the state level, serving as the Secretary of the Pennsylvania Equal Rights League, as protests surrounding the prevention of African Americans on streetcars began to grow in intensity. Black men and women intermingled with white throngs and made their way to seats in cars before conductors noticed, only to be ejected from the cars once they were noticed.

On a summer night in 1866 a colored audience gathered in Sansom Street Hall to discuss the ejections of four women from the cars. The main speaker was Catto. He called for bodily defiance of the streetcar rule. In another time, that would be described as civil disobedience. A newspaper reported:

He recommended the gentlemen to vindicate their manhood and no longer suffer defenseless women and children to be assaulted or insulted with impunity by ruffianly conductors and drivers.

By the end of the year 1866, a few legislators who had opposed the old streetcar bill were coming around for the new one. In Washington, Congress was on the brink of granting votes to blacks in the reconstructed South. An African American writer contemplated the moment:

True, reforms move slowly, and it will require time and patience for the people who have been cradled in oppression and prejudice to become educated out of their false views. But there is no mistaking the fact that there is a better feeling and understanding existing between the white and colored people of this country than ever before.

The Equal Rights League

Immediately following the Civil War, Catto became a major figure in the Equal Rights League. In 1866, Catto joined forces with two older African American men – artist David Bowser and William Deas Forten, member of a prominent abolitionist family and uncle of educator of the Freedmen in the South during the Civil War, Charlotte Forten. These three men became the Equal Rights League’s Car Committee.

The Committee revised the streetcar bill, awarding damages of $500 per passenger against any streetcar company or employee that barred passengers “on account of color, or race, or who shall refuse to carry such person… or who shall throw any car, or cars, from the track, thereby preventing persons from riding.” Violators would be fined $100 to $500, or jailed for up to 90 days.

Catto then moved the battle to the State House in Harrisburg to solicit the support of legislators. In Harrisburg on February 5, 1867, the bill drafted by the League’s car committee was introduced to the state legislature. Democrats attempted to poison the bill with parliamentary maneuvers, but the Republican majority forced a roll call – and by a vote of 50 to 27, the streetcars were opened to passengers of color.

Saturday’s Philadelphia Press reported that Republican Governor John W. Geary signed the bill on Friday, March 22, 1867. The new law explicitly stated that any service given or withheld on account of race was prohibited, including compelling riders to sit in special seats or seating them apart from other riders. All that remained was to find just the right person to test the law in the streets.

Le Count Tests the Law

By 1867 Caroline Le Count, principal of Philadelphia’s Ohio School, was engaged to be married to black rights activist Octavius Catto. Catto’s position at the Institute and his growing reputation made him one of the most eligible bachelors in the city. He was very popular with the opposite sex, but by 1867 Catto had decided on the girl he wished to marry: Caroline Le Count. They had similar interests, and both were important contributors to the education and equal rights of blacks in the city of brotherly love.

Le Count had also been part of a women’s resistance campaign based on civil disobedience for quite some time. In the Philadelphia newspaper, The Christian Recorder, Le Count’s name had often appeared among those who had been forcibly ejected from streetcars since 1862. Abolitionist Harriet Tubman and author Frances Ellen Watkins Harper had also been forced off.

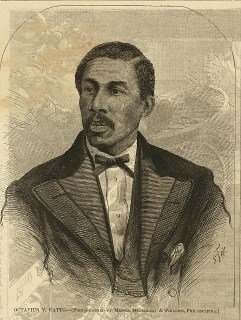

Image: Octavius Valentine Catto

Image: Octavius Valentine Catto

Catto and Caroline Le Count were leaders in the fight to desegregrate horse-drawn streetcars in Philadelphia. There are no known surviving images of Le Count.

On Monday, March 25, 1867, three days after the General Assembly passed the bill desegregating streetcars, Caroline Le Count and her assistant walked to Eleventh and Lombard Streets, where the Tenth and Eleventh Street Railway ran. The assistant, Alice Gordon, watched as the principal Caroline Le Count flagged down the yellow car and caught the attention of the conductor.

His name was Edwin F. Thompson, and he looked right back at Le Count, but the car kept moving. He “sneered at her,” and uttered the same words heard by colored soldiers and their loved ones: “We don’t allow N…… to ride!” Just a month past her 21st birthday, Le Count promptly filed a complaint in court, holding up a copy of the Press with the news that the governor had signed the law. The magistrate said, “I know nothing of a new law, and I do not trust that paper.”

Le Count then took the matter to the office of Secretary of the Commonwealth where she obtained a copy of the legislation, and presented it to the magistrate. The state law was upheld and the conductor was arrested and fined $100 for his actions. In the days that followed, Philadelphia’s eighteen street car companies were put on notice that segregation would not be tolerated, ending what had been almost a decade-long civil rights battle.

The National Antislavery Standard concluded that:

Henceforward, the wearied school-teacher, returning from her arduous day’s labor, shall not be condemned to walk to her distant home through cold and heat and storm; henceforward invalid women and aged men shall be permitted to avail themselves of a public conveyance, even though their complexion may not be white.

The victory belonged not only to Caroline Le Count, but to the network of African American women’s groups she worked with – women who had identified freedom of movement as one of their greatest obstacles to success. These organizations served the needs of escaped slaves, wartime refugees and black soldiers. It included the Ladies’ Union Association of Philadelphia, the Soldiers’ Relief Association, the Colored Women’s Sanitary Commission, and the Pennsylvania Freedmen’s Relief Association.

In the summer of 1871, Octavius Catto returned to Washington to aid in the administration of the freedmen schools. His travels to the capital increased his interest in politics. He returned to Philadelphia in early October 1871 to continue teaching at the Institute for Colored Youth and supporting equal rights for blacks.

The Assassination

In February 1871, Catto’s work in defense of freedom for black Americans was validated when Pennsylvania ratified the 15th Amendment, which granted black males the right to vote. These newly enfranchised blacks, who almost exclusively supported Republican candidates, posed a significant threat to Democratic leaders, who relied heavily on white Irish support.

The 1871 Philadelphia mayoral election – the first since the passage of the 15th Amendment – was marred by mob violence, as opponents tried to prevent African Americans from going to the polls. On Election Day, October 10, a fight between black and white voters two blocks away from the institute spread throughout the black sections. Students at the institute were dismissed at the first signs of disorder so that they might arrive at home before the situation became more serious.

As Irish rioters attempted to suppress the black vote, largely by violent means, Octavius Catto left the Institute to go to the polls. As he proceeded down Ninth Street onto South Street a white man with a bandage on his head came up from behind and called out to Catto. Cognizant of the gun the man held in his hand, Catto attempted to escape, but he was shot three times, killing him instantly.

The man, later identified as Irish protestor Frank Kelly, ran from the scene while numerous citizens stood staring at the bleeding body lying in the street. The body was moved to a nearby police station where, in a heartrending scene, Caroline LeCount identified her fiance’s body. Frank Kelly stood trial for his murder in 1877 but escaped conviction. Two other blacks met death and many whites and blacks were wounded before the melee subsided.

Catto’s death was mourned in the city, by both white and black. Thousands of whites and blacks lined the route of the funeral march to honor the fallen leader. Newspaper reports the next day judged the funeral to be the most elaborate ever held for a black person in America.

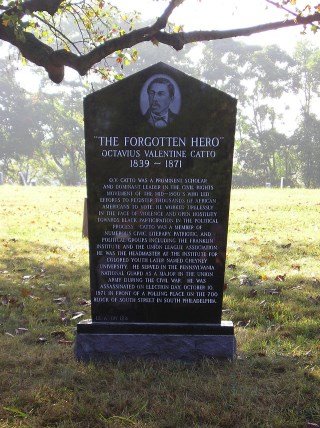

Image: Monument at the grave of Octavius Catto

Image: Monument at the grave of Octavius Catto

Catto’s assassination rallied his supporters in the Republican Party, which would dominate Philadelphia politics for the next 80 years, thanks in large part to black support. Succeeding generations of African Americans named buildings and professional organizations in Catto’s honor.

SOURCES

African Americans: Caroline Le Count

Pennsylvania History: Octavius V. Catto – PDF

Philly.com: City’s Post-Civil War Freedom Riders

Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia: Streetcars