Early Women Magazine Editors: Few and Far Between

Ladies’ Magazine (1827-1836) was the first American magazine edited by a woman: Sarah Josepha Hale. In 1837 it merged with Lady’s Book and Magazine to become Godey’s Lady’s Book. Hale moved from Boston to Philadelphia to edit the new magazine. She did not regret the move.

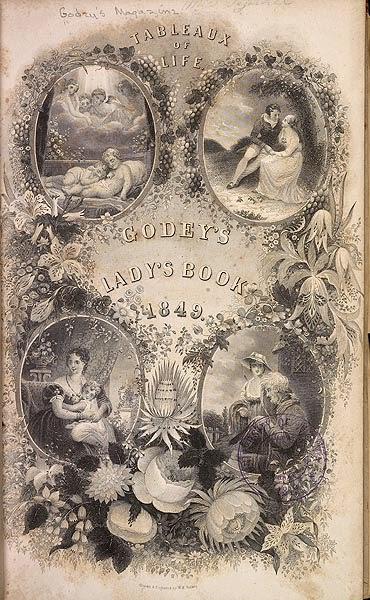

Image: 1849 Cover of Godey’s Lady’s Book

Sarah Josepha Hale, Editor

For the most part, women’s magazines of the nineteenth century focused on concerns seen as appropriate to woman’s sphere. Advertisers found the traditional home-centered woman to be an excellent customer for their clothing, cosmetics and household products; therefore, they preferred to patronize publications that would not lead women to question their place in society.

One reason for the delay in the appearance of American women’s magazines was the incredible distribution problem. Because of the sparse and scattered population, the only way to distribute magazines effectively was through the mail, which was not always reliable. By the time Louis A. Godey began Godey’s Ladies Book, the postal system had improved, so it was possible for magazines to have some measure of success.

Sarah Josepha Hale

Born in New Hampshire, Sarah Josepha Hale (1788-1879) was educated by her mother and older brother, which enabled her to teach for several years before she married David Hale in 1813. David’s unexpected death in 1822 left 34 year old Sarah with five children and no profession, in a time when respectable women could not properly earn money.

Sarah was set up in a millinery business by David Hale’s masonic colleagues. They also paid for the publication of a book of poems, The Genius of Oblivion and Other Original Poems. The modest success of this volume allowed Hale to leave the millinery business long enough to write a novel, Northwood (1827) which dealt directly with slavery.

Impressed by Northwood, the Reverend John Lauris Blake, Episcopal minister and headmaster of the Cornhill School for Young Ladies, offered Hale a job as editor of a new magazine for women. Hale was forced to make some difficult decisions. In order to support all of her children, she had to take the job and move to Boston, while leaving four of her five children behind to be raised by relatives in New Hampshire.

Sarah Josepha Hale was the first American woman to serve as editor of a magazine: Ladies’ Magazine (1827-1836). Hale envisioned her magazine as a platform for furthering the education of women. Though it added greatly to the difficulty of producing the periodical – she composed at least half the magazine herself – she required all contributions to be original works.

Louis Godey approached Hale in early 1836 about becoming editor of his magazine, Lady’s Book and Magazine, in Philadelphia, but she declined his offer in order to continue with her own publication and to remain in Boston. In 1837, Godey bought Ladies’ Magazine and merged it with his publication.

Hale then moved from Boston to Philadelphia as editor of the new magazine: Godey’s Lady’s Book (1837-1877). From that point on, Godey handled the business while Hale handled the content. Her work for the advancement and economic independence of women did not stop. Unlike many of her contemporaries, Hale insisted on the power of women within both the public and private spheres.

Throughout her long career, Hale helped popularize new ideas about reading and genre, and she made significant contributions to the development of professional authorship. In Godey’s, Hale reviewed thousands of books, wrote monthly editorials, and published the works of such writers as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Edgar Allan Poe, Harriet Beecher Stowe and Lydia Sigourney.

Although the magazine was read by and contained work by both men and women, Hale published three special issues which only included pieces written by women. She also published articles on a female health, proper dress, cooking techniques and recipes, education and other issues.

Image: Sarah Josepha Hale

From the February 1838 issue, in an article entitled “Why Women Were Made Lovely,” Sarah Josepha Hale wrote about the temptation of Eve, and the subsequent downfall of man:

Now the deduction I am about to draw from these premises will startle my fair readers, and I trust, provoke indignation of the males. My hypothesis is, that the scheme of creation has been misunderstood as regards the relative position of the two sexes, and that although the superior strength of man has helped him hitherto to maintain his self-created dignity of ‘Lord of All Creation.’ yet the intent of nature always was that, ultimately, the other should be the predominant sex. The conclusion is irresistible, that the time is not very far distant when male and female intellect will be generally on a par, and further, that in certain departments of mind, the latter will shoot ahead. When, however, the omnipotent fascination of beauty is added to this intellectual equality, or superiority, what on earth is to prevent the fair from being the dominant sex?

Hale made Godey’s the means of communication for women’s clubs, charitable projects, and included job advertisements. The magazine provided the opportunity for ordinary women to organize and achieve noteworthy projects. Hale herself organized the first women’s craft fair to raise money for charity. These charitable efforts were excellent lessons for women in their ability to organize and create a sense of unity among women.

Her steadfast devotion of purpose and her unwavering editorial principles regarding social inequalities and the education of American women, made Hale one of the most important editors of her time. In 1846 she stated:

The time of action is now. We have to sow the fields – the harvest is sure. The greatest triumph of this progression is redeeming woman from her inferior position and placing her side by side with man, a help-mate for him in all his pursuits.

Hale edited Godey’s Lady’s Book for the next forty years (1837-1877), expanding subscription rates from around 25,000 per month to nearly 150,000 by the end of the Civil War. Godey and Hale were a force to be reckoned with in American publishing, producing a magazine which is still considered one of the most important resources of 19th century American life and culture.

The importance of Hale’s influence in the advancement and education of women cannot be overstated. She was the first woman in so many ways.

Lydia Maria Child

An abolitionist, women’s rights activist, novelist and editor, Lydia Maria Child (1802-1880) founded the children’s magazine The Juvenile Miscellany in September 1826 and supervised its bimonthly publication until August 1834. The writers who contributed to its pages included Eliza Leslie, Catharine Maria Sedgwick, Lydia Sigourney, Hannah Flagg Gould, Caroline Gilman and Anna Maria Wells.

Lydia Child and her husband began to identify themselves with the anti-slavery cause in 1831 through the writings and personal influence of William Lloyd Garrison. It was Child’s belief that significant progress for women could not be made until slavery was abolished. She believed that white women and slaves were similar in that white men held both groups in subjugation and treated them as property, instead of human beings.

In August 1833, at the height of her success in Boston literary circles, and after years studying the subject of slavery, Lydia Maria Child published An Appeal in Favor of that Class of Americans Called Africans. The first book-length anti-slavery work of its kind, An Appeal bravely challenged all of the assumptions and prejudices of its day regarding the issue of slavery.

Child was praised by her supporters for her willingness to address issues many overlooked or avoided, such as racial prejudice in the North, the particularly difficult position of female slaves in relation to their white masters, integration and inter-racial marriage. But Child’s outspokenness cost her dearly. She was socially shunned; subscriptions to her magazine dropped dramatically, and she resigned as editor in 1834.

Sarah Josepha Hale (there she is again) edited The Juvenile Miscellany as a monthly between September 1834 and April 1836. Before leaving the magazine, Child wrote to her young readers:

After conducting the Miscellany for eight years, I am now compelled to bid a reluctant and most affectionate farewell to my little readers. May God bless you, my young friends, and impress deeply upon your hearts the conviction that all true excellence and happiness consists in living for others, not for yourselves…. I intend hereafter to write other books for your amusement and instruction; and I part from you with less pain, because I hope that God will enable me to be a medium of use to you, in some other form than the Miscellany.

Child spent the rest of her career writing and working to secure the rights of those pushed to the margins of American society. Her works were dedicated to securing the rights of free blacks after the Civil War, protesting against the mistreatment of Native Americans, and supporting the movement for equality for women.

And her fight to end slavery never waivered. In 1839, Child was elected to the executive committee of the American Anti-Slavery Society. She also served as a member of the executive board of the American Anti-Slavery Society during the 1840s and 1850s, alongside Lucretia Mott and Maria Weston Chapman.

In 1840, Lydia Maria Child became editor of National Anti-Slavery Standard, the official weekly newspaper of the American Anti-Slavery Society (1854–1865). It published the essays, debates and anything newsworthy concerning slavery. Its audience were members of the Society and other abolitionists. The paper only contained six columns, but its personal accounts of slavery helped express the feelings surrounding the controversy for thirty years.

Its publication began during a time when the Society was torn over the best way to accomplish emancipation. Lydia Child edited the Standard until 1843, when her husband David took her place as editor-in-chief. She acted as his assistant until May 1844. The paper was published continuously until the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1870.

Louisa Knapp Curtis

In 1875, Louisa Knapp (1851-1910) married Cyrus Curtis, publisher of The Peoples Lodge in Boston. After a fire destroyed that business, the couple moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1876 where her husband founded the Tribune and Farmer. Louisa wrote a column for the Tribune and Farmer magazine called ‘Women at Home.’

From that column, a separate magazine arose, entitled The Ladies Home Journal and Practical Housekeeper (1883); Curtis dropped the last three words from its title in 1886. She had great success with the Ladies’ Home Journal, which she edited in her home while raising her only child, Mary Louise.

Louisa Knapp Curtis remained as the editor of the monthly magazine from its first edition on February 16, 1883 until she turned over the editorship to Edward Bok in 1889, after which she continued to write a featured column for each issue.

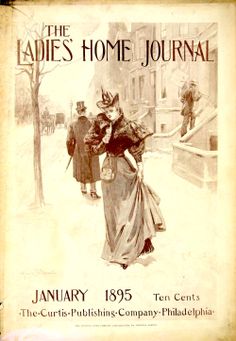

Image: January 1895 issue of Ladies’ Home Journal

Founded by Louisa Knapp Curtis in 1883

By 1889 the Journal had become one of the most popular magazines published in the United States, with half a million subscribers. In 1903, it became the first American magazine to reach 1 million subscribers.

On April 24, 2014, it was announced that the magazine would no long be published as a monthly with the July 2014 issue. The company stated that it was “transitioning Ladies’ Home Journal to a special interest publication.” It will now be available quarterly on newsstands only, though its Website remains in operation.

Other Nineteenth-Century Magazines Edited by Women

Among the smaller magazines of the era were Amelia Bloomer’s The Lily (1849) and Mrs. E.A. Aldrich’s The Genius of Liberty (1852-1854). Lucy Stone’s Woman’s Journal (1870-1917) provided a weekly voice for the suffrage fight. However, the readership for such magazines was relatively small.

Two major magazines began in the 1870s and 1880s, though not edited by women: McCall’s Magazine (1873) and Good Housekeeping (1885), which provided thorough, scientific information on gardening, cooking, sewing, interior design, and child care to housewives who increasingly viewed themselves as professionals. The Business Woman’s Journal (1889-1892) was completely owned and managed by women.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Godey’s Lady’s Book

Wikipedia: Ladies’ Home Journal

Godey’s Lady’s Book: Sarah Josepha Hale

National Abolition Hall of Fame and Museum: Lydia Maria Child

The History of Women’s Magazines: Magazines as Virtual Communities