Louisiana Author and Plantation Owner

Sarah Anne Ellis Dorsey was a novelist and historian from Louisiana. She published several novels and a highly regarded biography of Henry Watkins Allen, governor of Louisiana during the Civil War. It is considered an important contribution to the literature of the Lost Cause.

Early Years

Sarah Anne Ellis was born February 16, 1829 to Mary Malvina Routh Ellis and Thomas George Percy Ellis at the family estate in Natchez, Mississippi. Both of her parents were from wealthy families, and they owned plantations in Louisiana and Arkansas. Sarah was her serious-minded father’s joy, but he died in 1839 when she was nine.

Sarah’s widowed mother soon married financier Charles Gustavus Dahlgren, who saw great potential in Sarah and provided her with a first-rate education. He hired a tutor to teach her at home, and then sent her to Madame Deborah Grelaud’s French School in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

There Sarah excelled in music, painting, dancing and languages, quickly becoming fluent in Italian, Spanish, German and French. Sarah’s favorite teacher and closest friend there was Anne Lynch Botta. Sarah’s stepfather also had her trained in law and bookkeeping – not typical subjects for a woman in mid-19th century America.

From the 1840s onward, Anne Lynch Botta hosted a French-like salon for recognized thinkers. Among her guests were William Cullen Bryant, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Julia Ward Howe, Herman Melville and Catharine Maria Sedgwick. Edgar Allan Poe‘s “The Raven,” was first presented there.

Marriage and Family

In 1852, Sarah married Samuel Worthington Dorsey, an older man who was a member of a prominent Maryland family. Samuel inherited several large cotton plantations in the Tensas Parish region of northeastern Louisiana, where Sarah’s family also owned plantations. Between the Dahlgren-Routh-Ellis plantations on Sarah’s side and Samuel’s Louisiana plantations, the newlyweds were rich. They settled first in Maryland but soon moved to a Routh family estate near Newellton, Louisiana.

Dorsey had started as a struggling Vicksburg attorney but became a manager for the Dorsey and Routh plantations in Tensas Parish, Louisiana. He was no intellectual but a man of business, popular with his hunting and fishing neighbors. In the South of that era, Sarah could scarcely have found a male with comparable talents to her own. Stepfather Dahlgren was disappointed in her choice. “It was like wedding the living to the dead,” he told the bride.

The Civil War

When the Civil War began in 1861, the lavish entertainments and dinners at the Dorsey’s Elkridge Plantation in Louisiana came to an end. Sarah Dorsey, though an anti-secession Whig like her wealthy kinfolk and neighbors, plunged with gusto into work she thought patriotic. Her favorite soldier of glory was Reverend Leonidas Polk – Confederate brigadier-general, bishop of Louisiana, and West Point graduate. The war, however, was no romantic adventure.

In 1863, after Union General Ulysses S. Grant’s troops had burned her Elkridge mansion to the ground, Sarah and Samuel Dorsey led a hundred slaves to lands in East Texas. It was in the midst of working at a Confederate hospital that Sarah Dorsey began her literary career, probably as a means of escape from the ugly realities of war and the devastation of all that once had been taken for granted.

Literary Career

Casting about for a purpose in life other than being a wealthy plantation owner, Sarah Dorsey wrote many magazine articles for the New York Churchman in the 1850s, and between 1862 and 1877 she also wrote six novels and a biography. Her first novel Agnes Graham was serialized in 1863 in the Southern Literary Messenger and was published in book form in 1869.

Agnes Graham is a romantic novel about happier times in the upper ranks of Southern society, which features a heroine modeled on herself, who falls in love with her cousin, whom she plans to marry until she learns about their common blood line. Like her other novels, it was barely disguised autobiography.

In 1866, Dorsey published the biography of her close friend and the wartime governor of Louisiana, entitled Recollections of Henry Watkins Allen. She admired Allen’s work: “As a leader of wartime relief for the poor, an advocate of emancipation for slaves as reward for Confederate service, and other bold if not always welcomed innovations…” The highly regarded work is considered to be an important contribution to Lost Cause literature.

The postwar literary movement called the Lost Cause was a mixture of legend, mourning and anger that would dominate Southern memory for decades to come. Those who contributed to the movement portrayed the Confederacy’s cause as noble and its leaders far superior in military skill and courage, but were overwhelmed by the sheer numerical force of the Union armies.

At the time, women were considered ill-equipped to write biographies of politicians, or of any man for that matter. Dorsey was one of the few to successfully break the convention. She also used the biography to explain women’s indispensable contribution to the war effort and the hidden talents displayed by plantation women out of necessity in a time of war.

Other fictional works by Sarah Dorsey include the novel Lucia Dare (1867), whose fictionalized narrative is based on Dorsey’s experiences as she fled Louisiana for Texas during the Civil War. Her creative skill and compelling intensity with words were evident in this work, but critics hated it, complaining of its harsh realism.

She also published the novels Athalie (1872), which concerns women undertaking work to aid the poor; and Panola (1877), a far more popular fiction, which dissects the faults and weaknesses of the Louisiana elite. Two other novels, Vivacious Castine and The Vivians were written for the Church Intelligencer and were never published in book form.

Although the Dorseys suffered through Republican rule during Reconstruction, they still enjoyed a large income, which permitted them to escape by traveling abroad. Sarah met a number of English notables, including Lady Henrietta Maria Stanley, an ardent feminist who founded Girton College in Cambridge. Sarah was also fond of Anna Leonowens, later famed as the governess and heroine in Margaret Landon’s Anna and the King of Siam (1944).

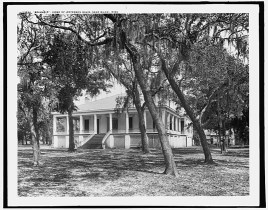

Beauvoir

In 1873, Samuel and Sarah Dorsey purchased a piece of beachfront property overlooking the Gulf of Mexico near Biloxi, Mississippi, which Sarah named Beauvoir (beautiful view). Sparkling water and a white sandy beach are visible from the front steps. They hoped that the move would improve Samuel’s failing health, but he died there in 1875.

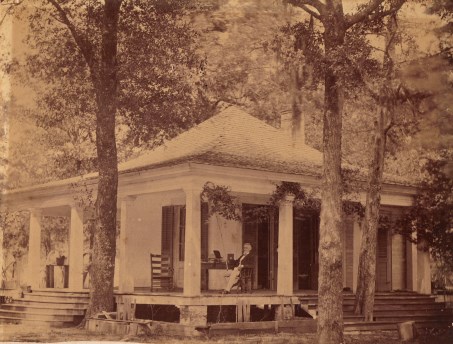

In December 1876 Sarah Dorsey learned that Jefferson Davis, former President of the Confederate States of America, was ill and bankrupt. Impoverished after his imprisonment, Davis and his wife had been living with their eldest daughter and her family in Memphis. Dorsey offered Jefferson Davis the use of the Library Cottage at Beauvoir to write his memoir.

Image: The Main House at Beauvoir

Jefferson Davis shocked even his most loyal supporters when he accepted Sarah Dorsey’s rather unconventional proposal to write his memoirs at her Gulf Coast estate; he moved in the following month. Dorsey had known Davis most of her life; she often visited Hurricane Plantation, the home of his elder brother Joseph on the Mississippi River south of Vicksburg.

If I understand the terms correctly, Jefferson Davis wrote a memoir of the Confederacy entitled Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government (1881) at Beauvoir, and later wrote his memoirs Autobiography of Jefferson Davis (1890) there. Davis began dictating Rise and Fall to Sarah Dorsey in February 1877.

Dorsey was instrumental in his success, organizing his day, motivating him to work, taking dictation, transcribing notes and editing his work. Davis, a chronic depressive, grew dependent on her encouragement and editorial advice. Rumors soon began to fly that Dorsey and Davis were having an illicit affair, but they refused to pay any attention to it.

Davis had been married since 1845 to his second wife, Varina Howell Davis, and Sarah and Varina had been childhood friends and classmates at Madame Grelaud’s school. Varina was in England when she learned of the arrangement from a newspaper article, and she was deeply hurt and refused to set foot on Dorsey’s property.

Late Years

When Varina Davis returned to the States from London in the fall of 1877, she refused to set foot on Dorsey’s property, but she finally joined her husband there in July 1878. When the last surviving Davis son, Jefferson Davis Jr., died of yellow fever that same year, the loss devastated both his parents. During that time, Varina Davis finally warmed to Dorsey’s hospitality, discretion and charm.

Soon after Varina returned to her daugthter’s home in Memphis, Sarah Dorsey was diagnosed with breast cancer. Realizing she was fatally ill, she rewrote her will in 1878, bequeathing all of her property to Jefferson Davis, the leader of a cause that had spelled ruin of all she held dear. Completely estranged from all of her Dahlgren kinfolk, she allotted them not a dime of her fortune, though some were quite poor.

Sarah Dorsey’s rewritten will:

Beauvoir, Harrison County, Mississippi

January 4, 1878I, Sarah Ann Dorsey of Tensas parish, Louisiana, being aware of the uncertainty of life and being now in sound health of mind and body, do make this my last will and testament, which I write, sign and seal with my own hand in the presence of three competent witnesses, as I possess property in the state of Louisiana, Mississippi and Arkansas, I owe no obligation of any sort whatsoever to any relative of my own. I have done all I could for them during my life.

I therefore give and bequeath all my property, real, personal and mixed, wherever located and situated, wholly and entirely without hindrance or qualification, to my most honored and esteemed friend Jefferson Davis, ex-president of the Confederate States, for his own sole use and benefit in fee simple and I hereby constitute him my sole heir, executor and administrator… I do not intend to share in the ingratitude of my country toward the man who is in my eyes the highest and noblest in existence…

Sarah Dorsey underwent surgery to remove the tumors in her breast, but it was unsuccessful. She died July 4, 1879 at the St. Charles Hotel in New Orleans at the age of fifty. Jefferson Davis was at her bedside.

Dorsey biographer Bertram Wyatt-Brown wrote:

Throughout her life, Sarah Anne Ellis Dorsey sought to combine the routines of a typical plantation lady with a sense of feminine intellectuality, which superior learning and wealth made possible. In comparison with Southern white women of similar tastes and high education, Sarah Dorsey… was much more experimental and extensive in her search for individuality… By her own choice, much of her life was confined to a rural existence. Yet she strived to open new avenues of intellectual experience without risk to her marriage or her social and economic position. Romantic by temperament, she thought that it would be easy to pursue an intellectual, productive career and give up nothing of her imposing style of living.

The Davises continued to live at Beauvoir. Although Varina hated the solace there, she was able to reconcile with her husband, and helped him complete his memoir, which was published in 1881.

Image: Jefferson Davis on the porch of the Library Cottage at Beauvoir

After Jefferson Davis died from acute bronchitis in 1889, Varina abandoned Beauvoir for New York City, where she earned a living as a writer and cultivated friendships with women such as Constance Cary Harrison and Julia Grant.

Before her own death in 1906, a liberated Varina Davis mustered the intellectual courage to declare that the right side had won the Civil War; enraging unreconstructed Rebels but freeing herself from the burden of her Confederate past.

In 1902 Varina Davis sold Beauvoir to the Mississippi Division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans with two stipulations: (1 that the property be used for a Confederate Veterans Home for veterans and or their widows at no charge to them, which was done from 1903 until 1957; (2 that the property then be used as a memorial to Jefferson Davis and the Confederate Soldier; that has been done from 1903 until the present.

Twelve barracks, a hospital, and a chapel were constructed on the Beauvoir land, home to as many as 250 veterans and their family members at peak operation.

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina caused extensive damage to the main house at Beauvoir and completely destroyed the Library Cottage, the museum building and several other structures. Many artifacts and documents were also severely damaged, destroyed or washed away. The main house was restored and reopened for tours in 2008. Renovation of the Jefferson Davis Presidential Library was deemed impossible and a completely new building has been constructed.

SOURCES

Sarah Anne Ellis Dorsey

Wikipedia: Sarah Dorsey

The Papers of Jefferson Davis: Beauvoir

Papers of Jefferson Davis: Sarah Anne Ellis Dorsey

Sarah Anne Ellis Dorsey: A Woman of Uncommon Mind