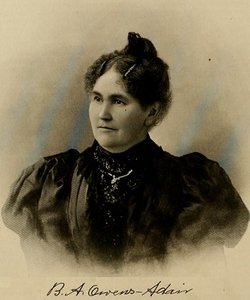

Pioneer Woman Doctor in Oregon

Bethenia Angelina Owens-Adair (1840 – September 11, 1926) was a social reformer and one of the first female physicians in Oregon Country with an MD (Doctor of Medicine). She was also a divorcee and a single mother, who overcame many hardships to fulfill her dream.

Bethenia Angelina Owens-Adair (1840 – September 11, 1926) was a social reformer and one of the first female physicians in Oregon Country with an MD (Doctor of Medicine). She was also a divorcee and a single mother, who overcame many hardships to fulfill her dream.

Some Oregon women, such as Mary Anna Cooke Thompson, called themselves doctor, but they had not attended medical school or earned medical degrees. Owens-Adair and Mary Priscilla Avery Sawtelle earned their medical degrees and established early practices in Oregon.

Early Years

Bethenia Angelina Owens was born on February 7, 1840, in Van Buren County, Missouri, the third of eleven children born to Tom and Sarah Damron Owens. As a daughter in a large family, Bethenia was expected to help raise her younger siblings, and she especially enjoyed nursing the sick.

The Owens family traveled to the Oregon Country via the Oregon Trail in 1843, when Bethenia was still a baby. The disruptions of pioneer life meant that Bethenia did not begin her formal education until age twelve, and her studies were interrupted again when her family moved from Astoria to Roseburg.

Great Migration of 1843

The Owens family took part in what became known as the Great Migration of 1843. An estimated 700 to 1,000 emigrants were included in that massive movement West. At Fort Hall, a trading post in the eastern Oregon Country, the pioneers were told that they should abandon their wagons there and use pack animals the rest of the way, but <a href=”https://www.womenhistoryblog.com/2012/08/narcissa-whitman.html”>Dr. Marcus Whitman</a>, an experienced guide, disagreed and volunteered to lead the wagons himself.

Whitman believed the wagon trains were large enough that they could build whatever road improvements they needed to make the trip with their wagons. The biggest obstacle they faced was in the Blue Mountains, where they had to cut and clear a trail through heavy timber. The wagons were stopped at The Dalles, Oregon because there was no road around Mount Hood.

The wagons had to be disassembled and floated down the treacherous Columbia River and the animals herded over the rough Lolo Trail to get around Mt. Hood. Nearly all of the settlers in the 1843 wagon trains arrived in the Willamette Valley of Oregon Country by early October. In 1846, the Barlow Road was completed around Mount Hood, providing a rough but passable wagon trail from the Missouri River to the Willamette Valley: about 2,000 miles. Migrations increased.

Excerpt from her autobiography, Dr. Owens-Adair; Some of her Life Experiences:

My father and mother crossed the plains with the first emigrant wagons of 1843, and settled on Clatsop plains, Clatsop County, Oregon, at the mouth of the Columbia, the wonderful River of the West, in sound of the ceaseless roar of that mightiest of oceans, the grand old Pacific. Though then very small and delicate in stature, and of a highly nervous and sensitive nature, I possessed a strong and vigorous constitution, and a most wonderful endurance and recuperative power.

Marriage and Family

At the age of 14, Owens married LeGrand Henderson Hill, one of her father’s farmhands. Bethenia and Hill moved to Yreka, California so Hill could join the California Gold Rush. There, at age 16, she gave birth to her only child, a son she named George.

The marriage was not a happy one. Her husband lost the family home to foreclosure and could not hold a job. The family suffered from poor living conditions and malnutrition, and Hill began to physically abuse his wife and child. Fearing for George’s well-being and her own, Bethenia divorced Hill in 1859, despite enormous social stigma against it.

At 19, she took back her maiden name and became a single mother. In Dr. Owens-Adair; Some of Her Life Experiences (1906), she stated:

I was, indeed, surrounded with difficulties seemingly insurmountable, – a husband for whom I had lost all love and respect; a divorce, the stigma of which would cling to me all my future life; and a sickly babe in my arms, all rose darkly before me.

When asked why she left her husband, Bethenia said:

Because he whipped my baby unmercifully and struck and choked me, and I was never born to be struck by mortal man.

When she divorced Hill, Bethenia knew she would be protected by her parents, but she was an independent woman, determined to provide for herself and her son. She reclaimed her maiden name and worked washing clothes, sewing, and taught school so she could complete her education.

Owens eventually returned to Roseburg in 1867 and began her professional life as an entrepreneur by opening a successful dressmaking and millinery business. She also became involved with the women’s suffrage movement, organizing <a href=”/2012/03/susan-b-anthony.html”>Susan B. Anthony</a>’s visit to Roseburg in 1871. Owens became friends with <a href=”/2012/09/abigail-scott-duniway.html”>Abigail Scott Duniway</a> and a subscription agent (1871-1887) and regular contributor to Duniway’s women’s rights newspaper the New Northwest.

Medical Education

After six years in business, in 1873 Owens decided she wanted to become a doctor. When she told family and friends, they were strongly opposed, including her own son. Women were not meant to be doctors! Women in Oregon had few opportunities for medical education, Owens found a local doctor who allowed her to borrow his medical books. She began her preparation by studying these books and providing lay care to her community.

Doors were closed to Owens-Adair because she was female. She confessed in her autobiography:

The regret of my life up to the age of thirty-five was, that I had not been born a boy, for I realized very early in life that a girl was hampered and hemmed in on all sides simply by the accident of sex.

There were few options for women to acquire a medical education. Women found more acceptance in unconventional medical practices, such as homeopathy, than they did in traditional medicine. These irregular practices were open to female students, and their doctrines paralleled the holistic and preventative medical focus that nineteenth-century women had used in caring for their families.

Owens was admitted to the Eclectic Medical College of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. The institution trained sectarian practitioners as homeopaths, hydropaths and eclectics. The curriculum of the school followed the eclectic model, which was a branch of medicine formed in the mid-nineteenth century which focused on botanical remedies.

Homeopathic medicine, is a medical philosophy and practice based on the idea that the body has the ability to heal itself. Homeopathic medicine views symptoms of illness as normal responses of the body as it attempts to regain health. It is based on the idea that, if a substance causes a symptom in a healthy person, giving the person a very small amount of the same substance may enhance the body’s normal healing and self-regulatory processes.

Eclectic medicine was a branch of American medicine which made use of botanical remedies and physical therapy practices, and was popular in the latter half of the 19th century. The term was coined by Constantine Rafinesque, a physician who lived among Native Americans and observed their use of medicinal plants.

Rafinesque used the word eclectic to refer to those physicians who employed whatever was beneficial to their patients. Regular medicine at the time made extensive use of purges with calomel and other mercury-based remedies, as well as extensive bloodletting. Eclectic medicine was a direct reaction to those barbaric practices.

Medical Practice

In 1873, Owens arranged for George, age 17, to board with Abigail Scott Duniway and work for her newspaper, while Bethenia headed east and enrolled in the Eclectic Medical College of Pennsylvania. A year later she returned to Oregon with her medical degree and opened an office in Portland, specializing in the care of women and children.

Her friends thought she was foolish to leave a profitable practice, but Bethenia Owens wanted a traditional medical degree from a reputable institution. In the fall of 1878 she enrolled in the University of Michigan’s Medical School, and received a Doctor of Medicine degree in 1880 at the age of forty. She spent the following summer doing clinical and hospital work in Chicago, postgraduate work at the University of Michigan and touring European hospitals.

In 1881, Owens returned to Oregon. She is often described as ‘the first woman doctor in the West,’ though historians might dispute the honor. Her MD degree distinguished her from previous women practitioners who worked as physician, but lacked formal training. Her new specialty was diseases of the eyes and ears with the majority of her patients still being women and children. Her son George also became a doctor.

At age 44, she married Colonel John Adair, a childhood friend. Bethenia gave birth to a child in 1887 at the age of forty-seven but the child only lived three days. They adopted two boys and lived on a farm near Astoria, Oregon for eleven years. There Bethenia had a general practice as a country doctor, and “at no time did [she] ever refuse a call, day or night, rain or shine.”

Dr. Owens-Adair worked for the temperance cause and promoted eugenics – a social movement that claimed to improve populations through sterilization. Like many doctors and scientists of the time, Owens-Adair was led to believe that socially undesirable traits, such as criminal behavior, mental illness and developmental disability, were hereditary and could be controlled through eugenics.

In 1922, she published Human Sterilization: Its Social and Legislative Aspects, which was well-received and brought her national recognition. Her writing reveals that she was motivated by a genuine concern for human well-being. Owens-Adair was a proponent of one of the most infamous practices of eugenics, the mandatory sterilization of those whom authorities found unfit to procreate.

She advocated for the 1925 Oregon statute that created the State Board of Eugenics. More than 2,500 individuals in Oregon’s prisons and mental institutions were forcibly sterilized as a result of this legislation. Some writers celebrate Owens-Adair as an inspiration to future women doctors, glossing over her commitment to the eugenics movement.

However, others may benefit by observing that many exceptional practitioners, with the noblest intentions, can be misled. Eugenics is still officially permitted in the United States today. Between 2006 and 2010 close to 150 women were sterilized in California prisons without state approval. Between 1997 and 2010, the state paid $147,460 to doctors for tubal ligations.

In 1899 Dr. Owens-Adair and her husband moved to North Yakima, Washington, where her son Dr. George Hill was practicing medicine. After serving as a physician in Roseburg, Portland and Clatsop County, Oregon and in Yakima, Washington, Dr. Bethenia Owens-Adair retired from the practice of medicine in 1905, at age 65.

Her husband died in 1915, and she followed him September 11, 1926 at the age of eighty-six.

This is an excerpt from the introduction to her autobiography, Dr. Owens-Adair; Some of her Life Experiences (1906):

In giving this book to the public, I have a two-fold purpose –

First: A desire to assist in the preservation of the early history of Oregon;

Second: Through the story of my life, and the few selections from my earliest and later writings… I have endeavored to show how the pioneer women labored and struggled to gain an entrance into the various avenues of industry, and to make it respectable to earn her honest bread by the side of her brother, man.

In this day and age of progress and plenty, women are found in all the pursuits of life, from the cradle to the grave, and it is hard now, and will be more so, for women a century hence, to believe what their privileges have cost their early mothers in tears, anguish, and contumely, as they ascended, step by step, that slippery and dangerous highway, clinging courageously to the rope and tackle of progress, taking in the slack here and there, never flinching, and never turning

back…

In her autobiography, the following line appears before the Table of Contents; it must be a subtitle of some sort: Gleanings from a Pioneer Woman Physician’s Life

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Great Migration of 1843

Wikipedia: Bethenia Angelina Owens-Adair

Oregon Encyclopedia: Bethenia Owens-Adair

Dr. Owens-Adair; Some of her Life Experiences