Civil War Women Working in Hospitals

In Union hospitals, the term matron referred to the woman who had the responsibility of supervising the wards in general hospitals – large military facilities in Northern cities, far away from the battlefields. Running hospitals during the war taught women that they could be leaders, and that the limitations society placed on them could sometimes be changed.

Union Hotel Hospital

Washington, DC

The Union Hotel and Tavern, built in Washington, DC in 1796, hosted many prominent citizens through the years including Robert Fulton, George Washington and John Quincy Adams. By the time of the Civil War, this once glorious hotel had become a boarding house. On May 6,1861, John Waters, the proprietor of the hotel, was notified by the government to remove all occupants from the building so it could be turned into a hospital.

Hannah Ropes

When her husband abandoned his family, Hannah Ropes raised their two children alone. As the head of her own household, she became active in her community as a nurse and a member of the abolitionist movement. Ropes was over 50 and her children were grown when the war started. Nonetheless, in June 1862, Ropes settled her affairs at her Massachusetts home and traveled to Washington, DC to volunteer her services.

Ropes was assigned as matron at Union Hotel Hospital in the Washington, DC neighborhood of Georgetown, one of the poorest facilities in the area. Ropes took steps to improve conditions for the soldiers being cared for there. When the surgeon in charge of the hospital refused to assist in her efforts, she took her complaints to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, resulting in the arrest of the chief surgeon and steward of the hospital.

In her published diary and letters, Ropes spoke often of her particular regard for the enlisted man. In October 1862, she wrote, “The poor privates are my special children of the present,” and described “the loss they have experienced in health, in spirits, in weakened faith in man, as well as shattered hope in themselves.”

On December 12, 1862, Louisa May Alcott came from Concord, Massachusetts to volunteer as a nurse and was assigned to the Union Hotel Hospital. Rushing about she was required to wash, dress and feed the men in her ward. These were difficult tasks for a young woman just leaving her family home for the first time. Alcott was impressed by Matron Ropes and her genuine concern for her patients.

The heavy work load of the nurses at the Union Hotel Hospital increased greatly when thousands of wounded soldiers arrived from the Battle of Fredericksburg (December 11-15, 1862), overwhelming the capital’s medical facilities. In her book about her nursing experiences, Hospital Sketches, Alcott described the scene as more casualties arrived:

There they were! “our brave boys,” as the papers justly call them, for cowards could hardly have been so riddled with shot and shell, so torn and shattered, nor have borne suffering for which we have no name with an uncomplaining fortitude, which made one glad to cherish each as a brother. In they came, some on stretchers, some in men’s arms, some feebly staggering along propped on rude crutches, and one lay stark and still with covered face, as a comrade gave his name to be recorded before they carried him away to the dead house.

All was hurry and confusion; the hall was full of these wrecks of humanity, for the most exhausted could not reach a bed till duly ticketed and registered; the walls were lined with rows of such as could sit, the floor covered with the more disabled, the steps and doorways filled with helpers and lookers on; the sound of many feet and voices made that usually quiet hour as noisy as noon; and, in the midst of it all, the matron’s motherly face brought more comfort to many a poor soul, than the cordial draughts she administered, or the cheery words that welcomed all, making of the hospital a home.

Working long hours in frigid and unhealthy conditions took its toll on the nursing staff during the following weeks. On January 9, 1863, Hannah Ropes wrote in her last letter to her son, briefly mentioning that she and Miss Alcott had “worked together over four dying men and saved all but one… we both took cold… and have pneumonia and have suffered terribly.”

Image: Hannah Ropes

Image: Hannah Ropes

Matron at Union Hotel Hospital

Washington, DC

Unfortunately, their ailment was not the normal variety of pneumonia; it was typhoid pneumonia – the major killer of wounded soldiers – with the symptoms of pneumonia and typhoid fever combined. Despite her condition, Ropes also wrote a telegram to be sent to Bronson Alcott, urging him to come to Georgetown and take his critically ill daughter Louisa back home, away from the diseased atmosphere in which she now suffered.

Alcott recorded her view of the dire situation:

Ordered to keep to my room, being threatened with pneumonia. Sharp pain in the side, cough, fever & dizziness… try to talk and keep merry but fail decidedly as day after day goes & I feel no better. Dream awfully & wake unrefreshed, think of home & wonder if I am to die here as Mrs. Ropes the matron is likely to do. Feel too miserable to care much what becomes of me… They want me to go home but I won’t yet…

On January 16, Louisa described her conflicting feelings of “amazement and anger to see my father enter the room that evening, having been telegraphed to by order of Mrs. Ropes without asking leave. I was very angry at first, though glad to see him, because I knew I should have to go…” However, the doctors determined that Louisa was then too weak to travel the distance to her home.

Soon after, Hannah’s daughter Alice was summoned to come and care for her dying mother. Alice sent a dismal update from the hospital on January 19, 1863 to her brother Edward, who had been struggling to recuperate from his own illnesses. “Mother had been ill for some weeks and indeed nearly all the nurses ill, so they sent for me to help a little,” Alice wrote.

Less than twenty four hours later, on January 20, 1863, Hannah Ropes died at the age of 53. The news raced throughout the wards, and frightened the hospital staff as they mourned the passing of Matron Ropes. The following day, Alcott returned home, where she suffered a long recovery, her nursing career coming to a close six weeks after it began

Charlotte Bradford

During the early months of 1863, Civil War nurse Charlotte Bradford from Duxbury, Massachusetts was recovering from a bout of illness, possibly typhoid fever contracted during her previous work with sick Union soldiers. Bradford had previously served as a U.S. Army nurse under Dorothea Dix and aboard the United States Sanitary Commission’s (USSC) Hospital Ships. Bradford also kept a diary of her experiences.

While Bradford was recuperating, her friend and fellow hospital ship nurse Amy Morris Bradley left her position as matron at the United States Sanitary Commission’s Home for Soldiers, leaving a vacancy perfectly suited to Bradford’s talents. The Home for Soldiers in Washington, DC was a place where men who had been furloughed by the Army could receive food, shelter and hospital care as they made their way North.

After accepting the position as matron, Bradford’s first days at the Home for Soldiers were spent cleaning and getting the place in order. Her days were hectic as she tended to men often too sick to travel any farther, or offered shelter to those who were waiting for their transportation papers to arrive. The Home also served as additional space when army hospitals became overcrowded. In 1863 alone over 900 critically ill patients were cared for there.

In addition to her duties as matron, Charlotte also managed the Home for Wives and Mothers a few doors down at 380 Capital Street. This facility housed the wives, mothers and sisters who flocked to the capital to care for their loved ones, often arriving “utterly ignorant of the cost of the journey, and of obtaining board or lodging, even for a day or two, in the city… utterly destitute and helpless.”

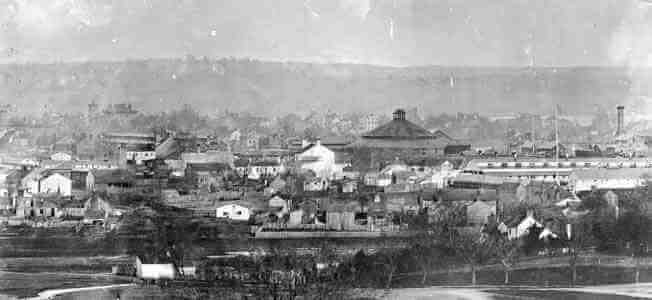

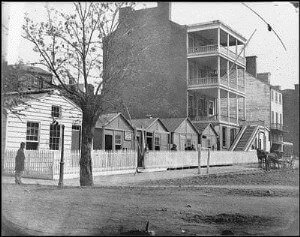

Image: Buildings of the Home for Soldiers and the Home for Wives and Mothers

Image: Buildings of the Home for Soldiers and the Home for Wives and Mothers

Washington, DC

The Home for Wives and Mothers offered female relatives of wounded soldiers not only shelter and food, but also assistance in locating their family members, sometimes their remains. Charlotte worked at the Home for Soldiers for the remainder of the war, not returning to Duxbury until the last veteran made his way through the Home in 1865.

In 1890, then seventy-six years old, she applied for and received a pension of $12 per month from the Federal government. Her petition stated that she was in dire straits and required “outside pecuniary assistance.” The Army Nurses Pension Act, which recognized women’s war work, did not pass until 1892, but Charlotte received word that her pension had been approved on May 16, 1890. She died In 1893.

Matrons in Confederate Hospitals

The position of matron was more important and prestigious in the Confederacy. It was established by legislation passed on November 25, 1862. Each hospital was to have two chief matrons to supervise the entire “domestic economy” of the hospital. There were also two assistant matrons in charge of the laundry and patients’ clothing, and two ward matrons for each ward of 100 patients, who made sure that each patient received suitable bedding, food and medicine.

In practice, the number of matrons depended upon the size of the hospital and the willingness of the doctor in charge to appoint them. Their duties also varied, involving many kinds of hands-on hospital work in addition to their supervisory roles. Matrons often cooked for patients on special diets, making toddies or eggnog, in order to appeal to delicate appetites. Matrons sometimes fed the patients as well.

Matrons also comforted patients, offered spiritual counsel, sat with the dying, and wrote to patients’ families to inform them of the location their loved ones. These women worked long hours, in some cases from 4:00 a.m. until midnight. Many became ill from exhaustion and disease, and had to leave the hospital to recuperate.

Phoebe Yates Pember

The Confederate States of America passed the “Matron Law” in September 1862, which permitted able-bodied doctors to be on the battlefields to tend to patients. Then, administrative control of hospitals could be given to women and non-physicians. Phoebe Yates Pember, a member of a prominent American Jewish family in Charleston, South Carolina, was one of the first women to serve as a hospital matron during the Civil War.

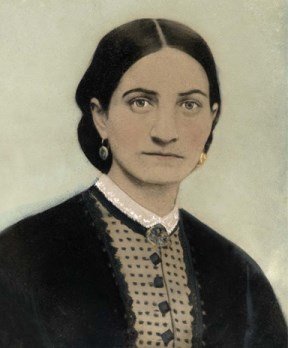

Image: Phoebe Yates Pember

Image: Phoebe Yates Pember

Matron at Chimborazo Hospital

Richmond, Virginia

275 x 300

Phoebe soon received an offer to serve as matron of Chimborazo Hospital in Richmond, the largest military hospital in the world. Although she had no professional medical training, caring for her husband through years of battling tuberculosis (he died on July 9, 1861) qualified her for hospital work. On December 1, 1862, Pember reported for duty as chief matron of Chimborazo’s Second Division, one of five divisions. There, she would remain until the end of the war and beyond.

As the first female administrator appointed to Chimborazo, Pember offered the warmth and femininity craved by the soldiers, but she also fought against repeated attempts to undermine her authority. Much of the time this meant blocking efforts by the staff to steal supplies, especially whiskey. Her commitment to caring for the sick and wounded earned praise among Richmond society.

She assisted surgeons, applied dressings and sometimes merely sat with the critically ill. She dealt with shortages of medicine, food and equipment; surly, often uncooperative doctors; and a society that criticized women who worked in hospitals. Her response was dignified:

In the midst of suffering and death, hoping with those almost beyond hope in this world; praying by the bedside of the lonely and heart stricken; closing the eyes of the boys hardly old enough to realize man’s sorrows, much less suffer man’s fierce hate, a woman must soar beyond the conventional modesty considered correct under different circumstances.

A total of 76,000 patients were treated at Chimborazo by the end of the Civil War, and an estimated 15,000 soldiers were under Pember’s direct supervision in the 150 wards she managed. She remained at Chimborazo until the Confederate surrender in April 1865, staying with her patients after the fall of Richmond, until Federal authorities took control of the facility.

When her responsibilities in Richmond were completed, Pember returned to Savannah, and often traveled in the United States and Europe. Her memoirs A Southern Woman’s Story: Life in Confederate Richmond was published in 1879. It is considered a pioneering piece of women’s history. Pember died on March 4, 1913, at age 89, in Pittsburgh, and is buried in Laurel Grove Cemetery in Savannah, where an obelisk was erected in her memory.

Kate Cumming

Unlike the general hospitals of Virginia, which stayed in one place, the Army of Tennessee hospitals moved frequently, according to military conditions. Each hospital had a staff that included surgeons and assistant surgeons, a steward (manager and pharmacist), ward masters, matrons, nurses, cooks and laundresses. One of the women who worked as a matron in several Georgia hospitals was Kate Cumming.

Born in Edinburgh, Scotland circa 1830, Kate Cumming immigrated with her family to the United States, settling in Mobile, Alabama. Despite having no formal nursing training, Cumming decided to offer her services, much to the distress of her parents. She left Mobile in April 1862, along with forty other local women, including the novelist Augusta Evans for the Mississippi-Tennessee border. There, until June 1862, she cared for Confederate soldiers who had been injured at the Battle of Shiloh (April 1862).

Born in Edinburgh, Scotland circa 1830, Kate Cumming immigrated with her family to the United States, settling in Mobile, Alabama. Despite having no formal nursing training, Cumming decided to offer her services, much to the distress of her parents. She left Mobile in April 1862, along with forty other local women, including the novelist Augusta Evans for the Mississippi-Tennessee border. There, until June 1862, she cared for Confederate soldiers who had been injured at the Battle of Shiloh (April 1862).

Unlike most women nurses, Cumming continued as an active nurse for the duration of the war. At Chattanooga, Tennessee, she worked at Newsome Hospital for the next year. In September 1862 the Confederate government decreed that military hospitals could legally pay their nurses. Thus Cumming’s status changed from volunteer to professional, and she was officially enlisted in the Confederate Army Medical Department.

After the fall of Chattanooga in the summer of 1863, Cumming moved on to Georgia, where she served in numerous mobile field hospitals established throughout the state in response to the destruction inflicted by Union General William Tecumseh Sherman‘s army. As the military forces moved, so did these medical facilities. Cumming served in hospitals at Americus, Cherokee Springs, Dalton, Newnan and Ringgold, Georgia.

Cumming went home to Mobile, Alabama after the war. She published her record of her Civil War experiences, A Journal of Hospital Life in the Confederate Army of Tennessee from the Battle of Shiloh to the End of the War, in 1866. In 1874 she moved with her father to Birmingham, Alabama. Cumming never married, but made a life there as a teacher and an active member of the United Daughters of the Confederacy until her death on June 5, 1909.

SOURCES

New Georgia Encyclopedia: Kate Cumming

Northern Volunteer Nurses of America’s Civil War

The Matron of Chimborazo: Phoebe Yates Pember

Charlotte Bradford: Matron of the Home for Soldiers

Civil War Nurses Series: Interesting Facts about Northern Nurses