Civil War Nurse and Occasional Journalist

Harriet Ward Foote, the oldest child of George Augustus Foote, was born June 25, 1831 in Guilford, Connecticut, on a New England farm – one of those rocky hillsides of which the natives say a man must own two hundred acres at least, or he will starve to death. Harriet was a first cousin of the famous Beecher family, her father being the brother of Roxana Foote Beecher, Lyman Beecher’s first wife.

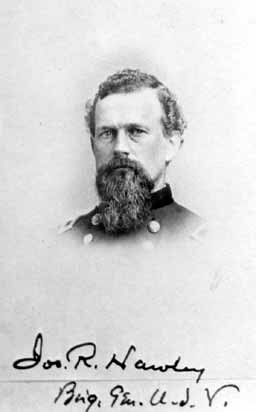

Joseph Russell Hawley

He was born October 31, 1826 in Stewartsville, Richmond County, North Carolina. In 1842 his family moved to Cazenovia, New York, where Joseph attended the Oneida Conference Seminary, and then graduated from Hamilton College in 1847. Hawley taught for two years, and then studied law with lawyer John Hooker, husband of Isabella Beecher Hooker.

In May 1850 Hawley was admitted to the bar and became John Hooker’s partner, and practicing law in Hartford, Connecticut for six years. Joseph Hawley was also an associate editor of the Hartford Evening Press with Charles Dudley Warner. On February 4, 1856, he called the first meeting in Connecticut to organize the Republican party with Gideon Welles. He was a political speaker for John Fremont in 1856.

Marriage

In the spring of 1854 Harriet Ward Foote met Joseph Hawley at John Hooker’s home in Hartford. On December 25, 1855 Foote married Hawley at her home in Guilford, Connecticut, and settled in a rented cottage in Nook Farm, adjacent to the property they would later purchase but never build on. Their neighbors at Nook Farm included Samuel Clemens and Harriet Beecher Stowe, and other literary luminaries living on the outskirts of Hartford.

The Hawleys in the Civil War

As a captain in the First Connecticut Infantry, Joseph Hawley was present at First Bull Run. Upon the receipt of Governor Buckingham’s proclamation to the people of Connecticut, Hawley and two others met in the office of his paper, and drew up and signed informal enlistment papers, as volunteers in the first regiment; and at a public meeting held the same evening, the list was filled, and the company was formed.

Hawley was made first lieutenant in Rifle Company A, First Regiment Connecticut Volunteers, which was mustered into service April 22, 1861, for three months. By the promotion of the colonel of the regiment soon after, Hawley became captain of his company, and displayed much activity in the organization and equipment of his men, for whom he ordered arms on his own personal credit, from the Sharpe Rifle Factory. The company disbanded on July 31, 1861.

After which he was appointed lieutenant colonel of a new, three-year regiment (organized August, 1861), the Seventh Connecticut. Rising to the colonelcy of the Seventh, Hawley participated in the unit’s battles along the Atlantic seaboard, eventually rising to brigade command.

He was a lieutenant colonel in the 7th Connecticut Infantry. He participated in the Port Royal Expedition in South Carolina in November 1861 and in the siege of Fort Pulaski in Georgia in April 1862. The regiment went into active service and Harriet did not go. In early 1862, she wrote her husband:

You must not think I’m grumbling when the longing, homesick feeling will break out sometimes. I know you feel it at times; and I do not know how you would bear it if you had not better work than I have. I do not mean to undervalue women’s work. You know I like to sew and I am glad to do anything, if it is only making a collar, to make the girls and mother happier, but I can’t help feeling when I’m doing these things that I throw a great deal more strength and energy into the work than things are worth.

I must work, and work steadily and hard, I can’t live without it, but I should like to feel that I was doing some real good to somebody. If I were sure of my health I would ‘compass Heaven and Earth’ to get some situation as nurse somewhere for the poor fellows who are spending their lives for us. It makes me sick to think that I can do nothing ; to think how we are going quietly on here at home when our best and bravest are suffering and dying, and the good cause goes on so slowly. I am not sure that I can bear it much longer – but I suppose I shall not do anything more desperate than knit a few pairs of stockings for the volunteers.

On April 15, 1862, she was clearly having issues with being separated from her husband, probably moreso than other army wives because she had no little ones at home to occupy her time and attention. (The Hawleys later adopted Harriet’s niece.) She wrote to Joseph:

I’m making up my mind pretty decidedly that you won’t be killed in this war, but will come home to a bigger fight here. There will be a thousand times more need of you here a year hence than there has been anywhere yet. I believe the Lord means to keep you in the world and get a good deal of solid work out of you.

Thank God that you are an honest man. I’d starve in rags or keep an ‘Irish boarding house’ sooner than that you should buy place or power by giving up one iota of principle. What folly it seems to care for anything but the right. This life seems such a short time to do even our duty in.

Joseph wrote to Harriet that it may be possible for her to join him, and she replied:

If the generals do not want women ’round, as I should think might be very likely, I can give it up entirely; I won’t come merely to please myself; it won’t be half as hard to give it up as to let you go at first – nor half as hard as to feel that I had coaxed you against your better judgment, and that I am a care to you there instead of a comfort.

Harriet joined Hawley in the South in November 1862, and became her husband’s confidential secretary and adviser, and the Seventh Connecticut Regiment honored her for her work. Wherever she joined her husband, she became teacher and nurse to his men and people in the surrounding areas, often without being assigned or directed. She saw the need, and did the work.

In a biography of her, written by her friend Maria Huntington and her sister Kate Foote and published in 1880, there are descriptions of the extensive nursing duties she took on during the Civil War in the various posts where she lived with her husband.

Women Journalists

Between January 2, 1863 and February 7, 1864, Harriet Foote Hawley wrote seven newspaper articles about her experiences in the South during the Civil War – four of which were written while with her husband who was serving in Florida. For a woman to have done this in that time was extraordinary. While many women recorded their experiences during the War, very few did so for newspapers.

Historian J. Cutler Andrews identified a few women who covered the conflict. Among over three hundred Yankees, Andrews found four women – Mary Clemmer Ames, Jane Grey Swisshelm, Grace Greenwood (pseudonym of Sara Jane Lippincott) and Laura Catherine Redden, whose pen name was Howard Glyndon.

Armory Square Hospital

Then in April 1864, Harriet was assigned to the hospital at Armory Square in Washington, starting a new ward, where none of her intimate friends were with her and where her life was such a round of trying labor, that she never put much of it into her letters. “It was terrible enough to live it, without

trying to reproduce it to others,” she said afterward.

The worst cases from the battlefields of the Army of the Potomac were brought there, because it was near the landing and because the rooms were airy. Her ward was large and as many as six men could die from their wounds in one day. She was on duty from six in the morning till ten at night, with only a few minutes for hurried meals. She wrote to her husband of the less trying and touching scenes, keeping her letters always cheerful.

Image: General Joseph Hawley

Image: General Joseph Hawley

With openings created by battlefield losses and reassignments, Joseph Hawley commanded a division during the Siege of Petersburg and was promoted to brigadier general in September 1864. In January 1865, Hawley succeeded his mentor Alfred Terry as divisional commander when Terry was sent to command troops in the attacks on Fort Fisher in North Carolina. Hawley later joined Terry in North Carolina as Chief of Staff for the X Corps.

After the Union captured Wilmington, Hawley took over command of the forces in southeastern North Carolina. Harriet joined her husband again and tended to many of the Union soldiers who had been released from Confederate prisons. In June 1865, following the surrender of the Confederate armies, Hawley rejoined Terry and served as Chief of Staff for the Department of Virginia, serving until October 1865, when he returned home to Connecticut.

Post War

After the war, Hawley held multiple political offices including governor of Connecticut (1866-1867) and state congressman (1873-1874). He then returned to his newspaper editing job where the Hartford Press and the Connecticut Courant were consolidated. He was president of the Republican national convention in 1868 and secretary of the committee on resolutions in 1872 and chairman of the committee on resolutions in 1876. He also led the United States Centennial Commission which organized the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia.

The Hawleys moved to Washington, DC, after Joseph was elected U. S. Senator in 1881 and held that position until his death. As a member of the Military Affairs Committee, he sought to reorganize the army, provide the navy with more modern warships, and upgrade the nation’s coastal defenses.

In the spring of 1885 the Hawleys adopted an orphaned niece, five-year-old Margaret Spencer Foote, the daughter of Harriet’s brother, Christopher Spencer Foote. Margaret Foote Hawley graduated from the Corcoran Art School, and became an accomplished artist. During her twenty-five-year career, she painted more than 400 miniatures, won numerous awards, and served as president of the American Society of Miniature Painters.

Harriet Foote Hawley died of pneumonia on March 3, 1886 at age 54.

In 1888 Hawley married Elizabeth Horner. They had two children and continued to raise Harriet’s niece, Margaret Foote Hawley.

Joseph Hawley died March 18, 1905 in Washington, DC, and is buried in Cedar Hill Cemetery in Hartford, Connecticut.

Excerpt from “Address of the Reverend Dr. Parker on Senator Hawley: Joint Report of the Commission on Memorials to the General Assembly of the State of Connecticut,” 1915:

In the Asylum Hill Congregational Church in Hartford, Connecticut, is a memorial tablet in honor of the noble woman who in 1855 became General Hawley’s wife, Harriet Foote Hawley, and who died in 1886. The veterans of the Seventh Connecticut Regiment placed it there in grateful remembrance of her ministrations and benefactions to the soldiers of that regiment during the Civil War. Its inscription reads, ‘By the grace of God, Harriet Foote Hawley lived a helpful life, brave, tender and true, a soldier and servant of Jesus Christ.’

SOURCES

One Foote in the Grave: Harriet Ward Foote

Internet Archive: Harriet Ward Foote Hawley

Colonel Joseph Russell Hawley: 7th Connecticut

Mark Twain’s Neighborhood: Harriet Foote Hawley