The U.S. Government and the Sea Island Slaves

Backstory

Backstory

In August 1861, at Fortress Monroe in Virginia, Union General Benjamin Butler declared that the slaves who escaped and came into his lines for protection were contraband of war, a term commonly used thereafter to describe this new status of slaves, which meant that the Army would not return escaped slaves to their masters. This would set the stage for a much larger undertaking at Port Royal a few months later.

Image: The Sea Islands during the Civil War

The Military

On November 7, 1861, just seven months after the Civil War began, the largest fleet ever assembled by the U. S. Navy, under the command of Commodore Samuel Du Pont, began bombarding Fort Walker and Fort Beauregard, the forts that guarded the entrance to South Carolina’s Port Royal Sound, one of the most important deep-water harbors between Florida and Virginia. Confederate forces retreated inland.

The U.S. Army then landed a ground force under General Thomas Sherman and occupied the Sea Islands. Plantation owners and other whites fled, leaving behind all of their major possessions, including large amounts of cotton from a record crop then in the process of being harvested and about 10,000 slaves, who would provide the Northerners their first view of slavery.

Those who would come to the Sea Islands to help these slaves in the coming years included Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Robert Gould Shaw, Robert Smalls, Harriet Tubman and Clara Barton. Working with them was Salmon P. Chase, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, Senator Charles Sumner and the American Missionary Society, among other social reform groups.

Late in November the Adjutant General ordered the seizure of all cotton and any other property that could be used for the U. S. Army. Paid labor would pick, collect and pack the cotton to be shipped in transports to the Quartermaster in New York, where it was sold.

Edward Pierce, personal secretary of Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase in President Lincoln’s cabinet, had worked with the slaves at Fortress Monroe. He wrote in great detail of his experiences in an article for the Atlantic Monthly, telling of the transformation from slavery to a free labor work force. The mission at Fortress Monroe set the stage for a much larger mission at Port Royal.

Brigadier General Rufus Saxton said, upon the arrival of Edward Pierce, the agent of the Treasury Department, “he will have little to do but take the credit of collecting a couple of million dollars’ worth of cotton.” The cotton which had already been picked and stored before the arrival of Du Pont’s fleet, Pierce thought there were 2,500,000 pounds, an estimate which indicates that the crop was unusually large.

The Slaves

For the slaves who lived on Port Royal, this was their first step toward freedom. Their legal status, however, was unclear: President Lincoln was not prepared to emancipate them, because he did not want to anger the leaders of the border states that remained in the Union – slavery continued to be legal in Kentucky and Delaware until after the war. He used the precedent set by General Butler at Fortress Monroe. The slaves were declared contraband of war; they would not be returned to their masters, nor were they considered free.

Many anti-slavery activists in the North recognized that Port Royal could provide the war’s first great opportunity to prove that free labor was superior to slave labor. Frederick Law Olmsted, the executive secretary of the United States Sanitary Commission, drafted a bill that would establish a framework for productively managing the plantations and ex-slaves, which was submitted to Congress.

In a letter to President Lincoln on March 8, 1862, Olmsted argued that the federal government had a duty to “save the lives of the negroes” and to “train or educate them in a few simple, essential and fundamental social duties of free men in civilized life.” Congress did not pass Olmsted’s bill, and the federal government never implemented a comprehensive plan.

The reality was that there were too many competing interests in Port Royal. Still, the ex-slaves and the Union officers helped turn Port Royal into a profitable source of cotton. The African Americans soon demonstrated their ability to work the land efficiently and live independently of white control by assigning themselves daily tasks for cotton growing.

However, many of the ex-slaves had no desire to continue raising cotton. Families who were given or bought their own land preferred to grow food crops – like corn and potatoes – that could help them and their families survive the following winter. By selling their surplus crops, thousands of former slaves acquired land parcels that would help sustain their families for generations.

Image: Port Royal Slave Quarters, April 1862

Image: Port Royal Slave Quarters, April 1862

Before the occupation, slaves in South Carolina could not carry guns, could not own land, and were forbidden to read and write. By 1863, African Americans were allowed to serve in the Union Army, and many of Port Royal’s best workers chose to fight. Nevertheless, many successful plantations developed, and the ex-slaves created a tightly knit community that endured into the 20th century.

Sea Island Cotton

As the Confederate Army and white plantation owners fled, Northerners began to capitalize on their possession of an area world famous for its cotton. The region’s climate and soil were suitable for cultivating Sea Island Cotton, the finest grade of cotton available, a very lucrative crop for local planters. The fiber can be spun into yarn two times finer than pima cotton, which is considered to be the next best grade.

During the first year of occupation African American field hands harvested approximately 90,000 pounds of Sea Island Cotton. The workers were paid $1 for every 400 pounds harvested and thus were the first former slaves freed by Union forces to earn wages for their labor. However, between boll weevil infestations and the devastation of the Civil War, the Sea Island Cotton industry was wiped out in almost a single season, never to return.

The Experiment

On January 15, 1862, Union General Thomas Sherman requested teachers from the North to train the ex-slaves. On February 4, 1862 the New England Freedmen’s Aid Society was formed in Boston. Its aims were to relieve bodily suffering; to give instructions in the rudiments of knowledge, morals, religion and civilized life; and to inform the public of the needs and rights of the freedmen. By March 6, thirty-eight teachers had been hired and $5,367.55 raised.

The salary of female teachers from the New England Freedmen’s Aid Society was $20 per month, besides shelter and ration; of male teachers $30 per month, besides shelter and ration. They were paid by the Treasurer of the Freedmen’s Aid Society. By 1865 they would employ fifty-four teachers: nine men and forty-five women. They would later teach the U.S. Colored Troops, including the Fifth Massachusetts Volunteer Cavalry and the 86th Infantry Regiment from the District of West Florida.

In February 1862, a report to Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase indicated that the territory held in the Port Royal Experiment included 14 islands and almost 200 plantations; 65 on the island of Port Royal, and 50 on St. Helena. On February 6, 1862, General Thomas Sherman wrote General Order No. 9, calling on Northern societies to help the freedmen and outlining the general plan for plantation labor and teachers.

In response to the obvious need for help, the government launched the Port Royal Experiment, an effort to assist freed blacks in making the difficult transition from slavery to freedom. Northern antislavery philanthropists saw the region as a field for missionary work, and they founded societies for the relief and education of the newly free islanders.

On March 9, 1862, Secretary Chase appointed Edward Pierce as a special agent of the Treasury Department to run schools, hospitals and plantations on the Sea Islands. A few days later Congress adopted an act forbidding U.S. military officers from returning fugitive slaves to their masters, and the states of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida were designated as the Department of the South under General David Hunter.

Treasury agent Edward Pierce arrived in April 1862, and began organizing programs to help the Sea Islanders become self-sufficient citizens. That same month the steamship Atlantic left New York City bound for Port Royal. On board were 53 missionaries including skilled teachers, ministers and doctors who had volunteered to help promote the experiment.

The Teachers

In April 1862, Laura Towne was sent South by the Port Royal Relief Committee of Philadelphia to help improve the lives of the freed slaves. Towne had studied medicine at the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania, but did not complete her degree because of the advent of war, but her expertise in homeopathic medicine would prove to be very useful. Initially, she distributed supplies, but as she traveled around the area, she noted the deplorable physical condition of the slaves and took on the medical care of many African Americans on the Sea Islands.

Penn School

Recognizing their strong desire to become self-sufficient citizens, Laura Towne soon realized that what the Islanders needed most was education. In June 1862 her first class for black children were held in a back room at the Oaks Plantation House, one of the mansions left empty when the whites fled. She began with only nine students, but enrollments quickly increased. In the summer of 1862, Bostonian Ellen Murray joined her friend Laura Towne on St. Helena Island, and they threw their energies into a larger educational mission.

In September 1862, the Towne and Murray founded the Penn School, named in honor of Pennsylvania Quaker William Penn, and relocated to the Brick Church. This was the first and would become one of the largest of the schools created for the Sea Islanders during the Port Royal Experiment. Murray, an experienced teacher, took over its day-to-day operation and served as its principal.

In October 1862, Charlotte Forten arrived at St. Helena. Her wealthy Philadelphia family had been free for generations and were always active in liberation causes. As a girl, she was sent to Salem, Massachusetts, where she was educated in interracial schools attended by children of radical abolitionists.

Forten was the first northern African American schoolteacher to go south to teach former slaves.

She lived with other missionaries in the abandoned mansion at the Oaks Plantation on St. Helena Island, and became the third teacher at the Penn School, where she worked with Towne and Murray for two years.

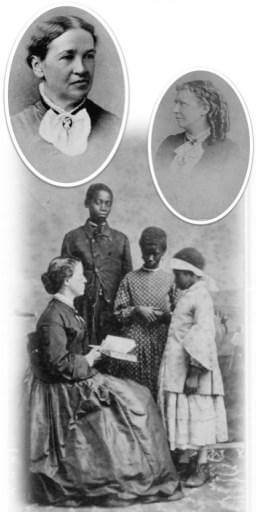

Image: Oval portraits of Laura Towne and Ellen Murray

Image: Oval portraits of Laura Towne and Ellen Murray

Below, Towne with three students: Dick, Maria and Amoretta

While many Northerners returned to the North after the end of Reconstruction, Towne spent the next forty years teaching and living among the people of the South Carolina Low Country, while living at Frogmore, a restored plantation on St. Helena Island. She developed their trust, provided them with medical care and fought for their land rights. Towne also adopted several African American children and raised them as her own.

Towne wrote: “I see every day why I came and what I am to stay for.”

Towne kept a detailed diary – Letters and diary of Laura M. Towne; written from the Sea Islands of South Carolina, 1862-1884 (1912) – describing the tumultuous times and the many challenges she faced at St. Helena. She was also a temperance supporter and a fierce fighter for women’s rights, especially the right to vote. Known for never backing down from threats to the well-being of African Americans, Towne remained true to her convictions throughout her life.

Laura Towne died of influenza on February 22, 1901, at the age of 75. Several hundred of her Sea Island neighbors followed the simple mule cart that carried her body to the Port Royal ferry, singing her favorite spirituals. She was buried at the Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia, and a memorial marker in her honor was erected at the Brick Church cemetery.

The End of the Dream

General Rufus B. Saxton was one of the great champions of the rights of freedpeople in the South, including the right to equality with white citizens and the right to land upon which they could support themselves. During the war, he served in Missouri and around Harper’s Ferry before being posted to Port Royal in 1862.

Most of the Sea Island plantations had been seized by the government for nonpayment of taxes under the authority of the U.S. Direct Tax Act of 1862. Concerned that the ex-slaves would not be allowed to keep their land, Saxton wrote a letter to Secretary Stanton dated December 7, 1862:

The prospect is that all the lands on these sea islands, will be bought up by speculators, and in that event, these helpless people may be placed more or less at the mercy of men devoid of principle, and their future well being jeopardized, thus defeating in a great measure the benevolent intention of the Government towards them.

To prevent this, and give the negroes a right in that soil to whose wealth they are destined in the future to contribute so largely, to save them from destitution, to enable them to take care of themselves, and prevent them from ever becoming a burden upon the country, I would most respectfully call your attention to the importance of the immediate passage of an act of Congress, empowering the President to appoint three Commissioners, whose duty it shall be to make allotments of portions of the lands forfeited to the US… to the emancipated negroes…

As the Union moved closer to victory in the Civil War, however, enthusiasm for the Port Royal Experiment began to wane. Many Northern whites, initially concerned about compensating African Americans for the injustices they had endured during slavery, now saw voting rights rather than land ownership as the key component to black progress. More conservative Northerners were increasingly uneasy about the precedent set by large scale land confiscation.

The death of President Abraham Lincoln in April 1865 ended momentum for the programs that were helping the former slaves. New President Andrew Johnson ended the Port Royal Experiment by ordering General Rufus Saxton to return all lands in the area to their previous white owners, dashing the hopes of many Sea Islanders for land ownership and independent lives.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Port Royal Experiment

BlackPast.org: Port Royal Experiment (1862-1865)

Emancipation Day: The Freed People of Port Royal

New York Times Opinionator: Rehearsal for Reconstruction