Black Heroines of the Civil War

Susie King Taylor

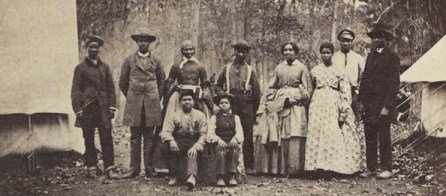

Born a slave in Savannah, Georgia in 1848, Susie King Taylor was 14 years old when the Union Army attacked nearby Fort Pulaski (April 1862). Taylor fled with her uncle’s family and other blacks to St. Simons Island, Georgia, where slaves were being liberated by the army. Since most blacks were illiterate, it was soon discovered that Taylor could read and write.

Susie King Taylor

Five days after her arrival, Commodore Louis Goldsborough offered Taylor books and supplies if she would establish a school on the island. She accepted the offer and became the first black teacher to openly instruct African Americans in Georgia. By day she taught children and at night she held a class for adults.

Captain Charles Trowbridge arrived at St. Simons to gather troops for what would become the 33rd Regiment of the First South Carolina Volunteers, which included former slaves from Florida, Georgia and South Carolina. These were the first African American soldiers in the Union army, and they continued to serve until they were disbanded January 31, 1866.

When Trowbridge and the Volunteers left St. Simon’s Island, Taylor was allowed to accompany them. Initially taken as a laundress, her duties expanded to include clerical work and nursing. For the next few years, she assisted the troops as they traveled and battled throughout South Carolina, Georgia and Florida.

Taylor’s experiences as a black employee of the Union Army are recounted in her diary, published as Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33rd United States Colored Troops Late 1st S.C. Volunteers:

Finally orders were received for the boys to prepare to take Fort Gregg, each man to take 150 rounds of cartridges, canteens of water, hard-tack, and salt beef. This order was sent three days prior to starting, to allow them to be in readiness. I helped as many as I could to pack haversacks and cartridge boxes… The fourth day, about five o’clock in the afternoon, the call was sounded, and I heard the first sergeant say, “Fall in, boys, fall in, and they were not long obeying the command…

I went with them as far as the landing, and watched them until they got out of sight, and then I returned to the camp. There was no one at camp but those left on picket and a few disabled soldiers, and one woman, a friend of mine, Mary Shaw, and it was lonesome and sad, now that the boys were gone, some never to return…

About four o’clock, July 2, the charge was made. The firing could be plainly heard in camp. I hastened down to the landing and remained there until eight o’clock that morning. When the wounded arrived, or rather began to arrive, the first one brought in was Samuel Anderson of our company. He was badly wounded. Then others of our boys, some with their legs off, arm gone, foot off, and wounds of all kinds imaginable. They had to wade through creeks and marshes, as they were discovered by the enemy and shelled very badly…

My work now began. I gave my assistance to try to alleviate their sufferings. I asked the doctor at the hospital what I could get for them to eat. They wanted soup, but that I could not get; but I had a few cans of condensed milk and some turtle eggs, so I thought I would try to make some custard. I had doubts as to my success, for cooking with turtle eggs was something new to me, but… the result was a very delicious custard. This I carried to the men, who enjoyed it very much.

My services were given at all times for the comfort of these men. I was on hand to assist whenever needed. I was enrolled as company laundress, but I did very little of it, because I was always busy doing other things through camp, and was employed all the time doing something for the officers and comrades.

Taylor served wherever she was needed most until the end of the war, after which she continued to teach illiterate African Americans.

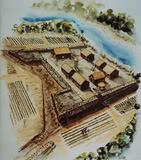

In 1862, Union forces occupied the Sea Islands off the coast of South Carolina. The white residents fled, leaving their plantations and thousands of slaves, who were then liberated by the Union Army. Port Royal and the surrounding Islands became the site of the first major attempts to aid the newly freed slaves, which was called the Port Royal Experiment.

Charlotte Forten

A young teacher and writer, Charlotte Forten (later Grimke) was a member of a well-educated family of well-to-do, free blacks in Philadelphia who were active in the abolitionist movement. Forten was one of many northern teachers who volunteered to help educate the ex-slaves and demonstrate that African Americans were capable of self-improvement.

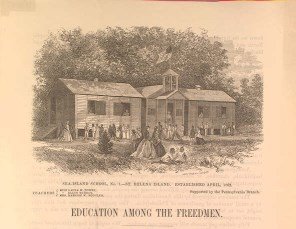

Image: Sea Island School for Liberated Slaves

Image: Sea Island School for Liberated Slaves

St. Helena Island, South Carolina

In this long essay Forten tells us about her teaching experiences as an African American northerner who went south to teach former slaves. The following are excerpts from that work:

In April [1863] we left Oaklands, which had always been considered a particularly unhealthy place during the summer, and came to Seaside, a plantation on another and healthier part of the island. The place contains nearly a hundred people. The house is large and comparatively comfortable…

On this, as on several other large plantations, there is a Praise-House, which is the special property of the people. Even in the old days of Slavery, they were allowed to hold meetings here; and they still keep up the custom. They assemble on several nights of the week, and on Sunday afternoons. First, they hold what is called the Praise-Meeting, which consists of singing, praying, and preaching… At the close of the Praise-Meeting they all shake hands with each other in the most solemn manner. Afterward, as a kind of appendix, they have a grand “shout,” during which they sing their own hymns…

Notwithstanding the heat, we determined to celebrate the Fourth of July as worthily as we could. The freed people and the children of the different schools assembled in the grove near the Baptist Church The flag was hung across the road, between two magnificent live-oaks, and the children, being grouped under it, sang The Star-Spangled Banner with much spirit…

Among the visitors present was the noble young Colonel Shaw [Robert Gould Shaw, commander of the 54th Massachusetts, the first unit of black soldiers to be raised in the North] whose regiment was then stationed on the island. We had met him a few nights before, when he came to our house to witness one of the people’s shouts. We looked upon him with the deepest interest. There was something in his face finer, more exquisite, than one often sees in a man’s face, yet it was full of courage and decision…

A few days afterwards we saw his regiment on dress-parade, and admired its remarkably fine and manly appearance. After taking supper with the Colonel we sat outside the tent, while some of his men entertained us with excellent singing. Every moment we became more and more charmed with him. How full of life and hope and lofty aspirations he was that night! How eagerly he expressed his wish that they might soon be ordered to Charleston! “I do hope they will give us a chance,” he said…

We never saw him afterward. In two short weeks came the terrible massacre at Fort Wagner, and the beautiful head of the young hero and martyr [Shaw] was laid low in the dust. Never shall we forget the heart-sickness with which we heard of his death. We could not realize it at first, we who had seen him so lately in all the strength and glory of his young manhood. For days we clung to a vain hope; then it fell away from us, and we knew that he was gone. We knew that he died gloriously, but still it seemed very hard. Our hearts bled for the mother whom he so loved,–for the young wife, left desolate…

During a few of the sad days which followed the attack on Fort Wagner, I was in one of the hospitals of Beaufort, occupied with the wounded soldiers of the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts. The first morning was spent in mending the bullet-holes and rents in their clothing. What a story they told! Some of the jackets of the poor fellows were literally cut in pieces. It was pleasant to see the brave, cheerful spirit among them.

Some of them were severely wounded, but they uttered no complaint; and in the letters which they dictated to their absent friends there was no word of regret, but the same cheerful tone throughout. They expressed an eager desire to get well, that they might “go at it again.” Their attachment to their young colonel was beautiful to see. They felt his death deeply…

The physical and emotional stress took its toll on Charlotte’s slender frame, and she began to experience periods of ill health and terrible headaches; she was forced to leave St. Helena and return to Philadelphia in 1864. After the Civil War, she worked with the Freedmen’s Relief Association in Boston to help former slaves find jobs and homes. In the late 1860s and 1870s, she worked for the U.S. Treasury Department in Washington, DC.

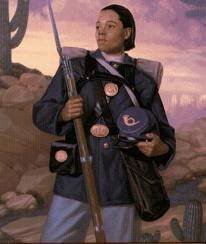

During the Civil War, black women’s services included nursing or domestic chores in medical settings, laundering and cooking for the soldiers. As the Union Army marched through the South and large numbers of freed black men enlisted, their female family members often obtained employment with the unit. The Union Army also paid black women to raise cotton on plantations for the northern government to sell.

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

Born free in Baltimore, Maryland, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper‘s family sold their home and fled to Canada when the racial climate in Maryland became increasingly hostile after the passage of the Compromise of 1850. Frances chose to move to Ohio, where she became the first woman instructor at the African Methodist Episcopal Union Seminary (now Wilberforce University) near Columbus, where she taught domestic science.

Image: Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

Image: Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

In 1855, Harper moved to Philadelphia and joined William Still, Chairman of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, in helping escaped slaves travel the Underground Railroad on their way to Canada. Leaders of the Philadelphia Underground Railroad refused to make Harper an agent because she was a woman, but she collected donations and forged friendships with Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman.

In support of the Free Produce movement which encouraged the boycott of products tied to slave labor, Harper asked, “Could slavery exist long if it did not sit on a commercial throne?” She argued that as long as people constantly demanded rice from the swamps, cotton from the plantations and sugar from the mills, their moral influence against slavery would be weakened and their testimony diluted.

This remarkable self-educated woman was referred to as the Brown Muse, and described as “a petite, dignified woman whose sharp black eyes and attractive face reveal her sensitive nature.” After emancipation, she wrote and lectured to ensure the equal rights of the newly-freed

slaves and continued her work to gain greater acceptance for all women as equals to men.

In 1893, Harper – with colleagues Fannie Barrier Williams, Anna Julia Cooper, Fannie Jackson Coppin, Sarah J Earley, and Hallie Quinn Brown – charged the international gathering of women at the World’s Congress of Representative Women in Chicago with indifference to the needs and concerns of African American women. As a result, she was active in the establishment of the National Association of Colored Women and became its vice president.

Excerpts from “Liberty For Slaves,” a speech given by Frances Ellen Watkins Harper in 1857:

Could we trace the record of every human heart, the aspirations of every immortal soul, perhaps we would find no man so imbruted and degraded that we could not trace the word liberty either written in living characters upon the soul or hidden away in some nook or corner of the heart. The law of liberty is the law of God, and is antecedent to all human legislation. It existed in the mind of Deity when He hung the first world upon its orbit and gave it liberty to gather light from the central sun…

Slavery is mean, because it tramples on the feeble and weak. A man comes with his affidavits from the South and hurries me before a commissioner; upon that evidence ex parte and alone he hitches me to the car of slavery and trails my womanhood in the dust. I stand at the threshold of the Supreme Court and ask for justice, simple justice. Upon my tortured heart is thrown the mocking words, “You are a negro; you have no rights which white men are bound to respect”!

As Union armies occupied Confederate states in the South, liberating more and more slaves, authorities began to employ these laborers for Federal benefit. Government officials placed women, children and men who were unfit for military service to work on abandoned plantations to raise cotton and food crops.

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin

An African American publisher, journalist and suffragist, Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin was also editor of Women’s Era, the first newspaper published by and for black women. Ruffin was born August 31, 1842 into one of Boston’s leading black families. In 1858, at the age of 15, she married George Lewis Ruffin. They bought a house on Boston’s Beacon Hill and became active in the anti-slavery movement.

During the Civil War, Ruffin helped recruit African American soldiers for the 54th and 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiments in the Union Army and worked for the United States Sanitary Commission. She also served on the Board of the Massachusetts Moral Education Association and the Massachusetts School Suffrage Association, working closely with other New England women leaders, including Julia Ward Howe and Lucy Stone.

Image: Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin

Image: Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin

Some of Ruffin’s greatest contributions came after the war, when her philanthropic work brought her in contact with many eminent white and black leaders, and her close friends included Susan B. Anthony, William Lloyd Garrison, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Booker T. Washington.

She is best known for her leadership role in establishing clubs for African American women. In 1894 Ruffin founded the Women’s Era Club, one the first African American women’s clubs. In 1895, she and women from other national groups organized the National Federation of Afro-American Women. Its mission was to draw attention to the existence of a large number of educated, cultured African-American women. At its founding meeting Ruffin said:

We are women, American women, as intensely interested in all that pertains to us as such as all other American women; we are not alienating or withdrawing, we are only coming to the front, willing to join any others in the same work and welcoming any others to join us.

In 1896 this group and the Colored Women’s League of Washington merged, becoming the National Association of Colored Women. Ruffin was elected its first vice-president, and she remained an active participant in that group throughout her life. Ruffin was also involved in the founding of the Boston branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

African American women saw the Civil War as an opportunity to fight oppression and end slavery. They also contributed to the war effort in various ways: as organizers, activists, nurses, cooks, camp workers and occasionally as spies. They worked in hospitals in the North and in the South; many of the nurses in the South were, in fact, African American women. Undoubtedly there are thousands whose names we will never know.

SOURCES

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin

Atlantic.com: Life on the Sea Islands

Decoded Past: Francis Watkins: A Woman of Words

National Women’s Hall of Fame: Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin

History Matters: Susie King Taylor Assists the First South Carolina Volunteers