Wife of Confederate Officer Sandie Pendleton

Early Years

Katharine Carter Corbin was born in July 1839 at the Laneville estate in King and Queen County, Virginia, the daughter of James Parke Corbin, whose family had lived in the Rappahannock River valley for generations. Richard Corbin succeeded Lord Dunmore and served as royal governor until the beginning of the American Revolution.

Kate and Sandie Pendleton

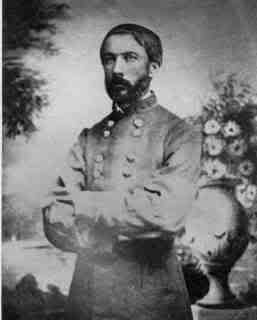

Alexander Sandie Pendleton was born September 28, 1840, near Alexandria, Virginia, the only son of Episcopal minister and future Confederate General William Pendleton and his wife Anzolette Elizabeth Page Pendleton. Sandie spent his childhood in Maryland until his father became rector of Grace Episcopal Church in Lexington, Virginia in October 1853.

In 1857, Sandie Pendleton graduated from Washington College in Lexington, Virginia, where he first met Thomas Jonathan Jackson, who was then on the faculty of the Virginia Military Institute, and who later gained iconic status in Confederate history as Stonewall Jackson. Two years later Sandie entered the University of Virginia to pursue a master’s degree. His graduate studies and plans to enter the ministry were cut short, however, when Virginia seceded from the Union in April 1861.

Sandie Pendleton in the Civil War

Pendleton received a commission as second lieutenant in the Provisional Army of Virginia and reported for duty to Harpers Ferry on June 14, 1861. There he temporarily worked with the Rockbridge Artillery, a volunteer unit his father had organized.

General Jackson was then commanding the First Brigade of General Joseph E. Johnston‘s Army of the Shenandoah in Harpers Ferry, and he remembered Sandie Pendleton from their days in Lexington. Within weeks, Jackson asked Pendleton to join his staff as a brigade ordnance officer. Pendleton soon showed his capabilities as a staff officer and his bravery at the First Battle of Bull Run, where Jackson earned the name Stonewall.

Pendleton became Jackson’s de facto chief of staff during the Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1862, and their relationship was a close one – it was said that Jackson “loved him like a son.” Pendleton served with distinction in the Valley Campaign, and in June he helped transport Jackson’s troops to Mechanicsville to surprise Union forces and protect Richmond.

Jackson recommended him for promotion to captain after the Valley Campaign. Pendleton was equally skilled in battle, relaying orders and encouraging troops, coordinating officers and units, or handling the endless paperwork that made the army run efficiently. When asked for information, Jackson always replied, “Ask Sandie Pendleton. If he does not know, no one does.”

Pendleton missed the Second Bull Run Campaign in August on sick leave, but had returned to duty when General Robert E. Lee first invaded the North in the summer of 1862 and the Battle of Antietam in Maryland on September 17. At one point during the battle, Pendleton described the scene:

Such a storm of balls I never conceived it possible for men to live through. Shot and shell shrieking and crashing, canister and bullets whistling and hissing most fiend-like through the air until you could almost see them. In that mile’s ride I never expected to come back alive.

After being slightly wounded at Fredericksburg in December 1862, Pendleton was promoted to major and permanent assignment as assistant adjutant general in the Army of Northern Virginia’s new Second Corps, commanded by Jackson. The two men became almost inseparable.

Kate and Sandie

Moss Neck Manor, the mansion at Moss Neck Plantation on thousands of acres near Fredericksburg, Virginia, is a sprawling 9000 square feet, 225 feet long, and features a columned front veranda. In the winter of 1862-1863, it was owned by Richard Corbin, who was away serving as a private in the 9th Virginia Cavalry. Living at the Manor that cold winter was Richard’s wife Roberta, their young daughter Janie, and his attractive twenty-three-old sister Kate Corbin.

General Stonewall Jackson used Moss Neck as his winter headquarters from December 1862 through March 1863. They arrived in mid-December, cold and hungry, but elated by the Confederate victory at Fredericksburg a few days earlier. The general declined an invitation to stay in the mansion, and was quoted as saying that it was “too luxurious for a soldier.” Tens of thousands of soldiers camped on the rolling hills of the plantation, and they felled many of the estate’s trees, which they used as firewood and to make log huts.

On Christmas Day 1862, General Robert E. Lee accepted an invitation to dine with General Stonewall Jackson at his winter headquarters on the grounds of Moss Neck Plantation. After sharing a meal at the outbuilding Jackson used as an office, General Lee bid his host farewell and headed back to his own headquarters.

Artist Mort Kunstler used the columned front facade of Moss Neck Manor as the backdrop of this very special painting, Merry Christmas General Lee, which depicts General Lee departing after dining with his most trusted friend and officer, Stonewall Jackson. Guests arriving for a holiday party at the mansion have stopped in their tracks on the veranda to offer greetings to the legendary rider passing by.

Artist Mort Kunstler used the columned front facade of Moss Neck Manor as the backdrop of this very special painting, Merry Christmas General Lee, which depicts General Lee departing after dining with his most trusted friend and officer, Stonewall Jackson. Guests arriving for a holiday party at the mansion have stopped in their tracks on the veranda to offer greetings to the legendary rider passing by.

Kate Corbin met Sandie Pendleton while General Jackson and his army were camping at Moss Neck. The two were engaged just before the Chancellorsville campaign, which began on April 27, 1863.

Chancellorsville Campaign

As plans for the spring campaign began to take shape in late April 1863, Union General Joseph Hooker, the new commander of the Army of the Potomac prepared for a new offensive in Virginia with an army of 130,000 men against General Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia of approximately 60,000 Confederates. Lee’s battle plan called for General Jackson to move stealthily around the right flank of the Union army through the narrow trails, gnarled trees and dense thickets of a forest known as the Wilderness.

On May 2, 1863, the valiant Jackson set off early in the morning with 28,000 men, but travel was so difficult that they did not reach their objective until the afternoon. Meanwhile General Lee and the rest of the Confederate army held the Union troops at bay at Chancellorsville, an isolated crossroads named for the family who lived in the only house there.

The troops on the Union army’s western flank were so oblivious to the impending danger that they were shocked when thousands of Rebels suddenly burst out of the woods firing and screaming their piercing rebel yell. The Union soldiers immediately began a disorderly retreat, which was slow going because of the terrain, and did not stop until they reached the safety of the main Union army.

Night was beginning to fall as Jackson and some of his staff rode out between the lines to plan another attack. Slowly finding their way back in the darkness, Jackson and his officers surprised a group of jittery Southern pickets who mistook them for Union cavalry. Two volleys burst forth in the blackness and Jackson was struck by three bullets: two in his left arm and one in his right hand. Struck by friendly fire.

Sandie Pendleton was on another part of the battlefield at that time, but came running as soon as he heard. Bleeding profusely, Jackson was carried on a litter to a nearby field hospital. None of Jackson’s three bullet wounds were in themselves life-threatening, but the bone in his left arm was shattered and it was amputated close to the shoulder later that evening.

Jackson was then moved to a house some 25 miles away to recover, but he contracted pneumonia and died on May 10, 1863; he was 39 years old. His death was a devastating loss to General Lee, his men and the Confederacy. Sandie Pendleton dressed Jackson’s body for burial after his death, and was a pallbearer at Jackson’s funeral. Pendleton told Jackson’s wife Mary Anna Morrison Jackson, “God knows, I would have died for him.”

After accompanying Jackson’s corpse to its final resting place in Lexington, Pendleton returned to duty with the Second Corps under its new commander, General Richard Ewell during the Gettysburg Campaign. Pendleton resigned his position, believing that Ewell would want to choose his replacement, but Ewell kept him, recommending him for promotion to lieutenant colonel and chief of staff in August 1863.

Kate Corbin married Sandie Pendleton on December 29, 1863 at Moss Neck Manor. My search for more information about their wedding and their marriage was unsuccessful.

In May 1864, General Lee replaced Ewell with General Jubal Early, but Pendleton kept the same position. He accompanied Early during the Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1864 with a new Army of the Valley, created with the Second Corps as its nucleus. Early promoted Pendleton to chief of staff with the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Battle of Fisher’s Hill

The Union assigned General Philip Sheridan to put down resistance in the valley once and for all. Following his defeat at the Third Battle of Winchester on September 19, 1864, Early withdrew and took up strong defensive positions at Fisher’s Hill, south of Strasburg. On September 21, the Federal army advanced, driving back skirmishers and capturing important high ground opposite the Confederate entrenchments.

The following day, USA General George Crook’s VIII Corps, hidden from Early’s view, moved along North Mountain to outflank the left of Early’s line. About 4:00 pm, Crook attacked Early’s flank, held only by Confederate cavalry who offered little resistance. As Crook began to roll up the Confederate line, Sheridan ordered a frontal assault.

Overwhelmed by Union forces from the front and rear, the Confederate defenders broke and ran to avoid capture. While trying to rally the Confederate troops streaming to the rear, Sandie Pendleton was fatally wounded in the abdomen on September 22, and was moved to the nearby town of Woodstock.

Lieutenant Colonel Sandie Pendleton died September 23, 1864, six days short of his 24th birthday, and was buried near the battlefield.

The following month Pendleton’s body was exhumed and returned to his family in Lexington. On October 24, 1864, his parents and his wife of nine months attended his reburial near General Jackson’s grave at Stonewall Jackson Memorial Cemetery in Lexington, Virginia.

Kate Corbin Pendleton was expecting their first child when her husband was mortally wounded at Fisher’s Hill. In November 1864, she gave birth to a son she named Sandie, but the child contracted diphtheria and died in September 1865. Kate has been quoted as saying:

I wonder people’s hearts don’t break. When they have ached and ached as mine has done till feeling seems to be almost worn out of them. My poor empty arms, with their sweet burden torn away forever.

On March 14, 1871, Kate Corbin Pendleton married former Confederate naval officer John Mercer Brooke, an American sailor, engineer, scientist and educator, who was instrumental in creating the Transatlantic Cable. Brooke was also professor of physics and astronomy at the Virginia Military Institute until 1899. Kate and John had three children: George Mercer Brooke, Rosa Johnston Brooke and Richard Corbin Brooke.

Kate Corbin Pendleton Brooke died in 1918 at Staten Island, New York. She and John Mercer Brooke are buried beside each other and near Sandie Pendleton in the Stonewall Jackson Cemetery in Lexington, Virginia.

Alexander Sandie Pendleton was a minor character in the Jeff Shaara book, Gods and Generals, and was portrayed by Jeremy London in the 2003 Civil War film of the same name.

SOURCES

The Washington Post

Virginia Military Instute

Wikipedia: Sandie Pendleton

Encyclopedia Virginia: Alexander S. Pendleton

Fredericksburg.com: At Moss Neck, it’s 1856 Again