The Savior of Hundreds of Slaves

Image: Harriet Tubman Leading The Way

Image: Harriet Tubman Leading The Way

After Harriet Tubman escaped from slavery, she returned to the South nineteen times and escorted hundreds of slaves to freedom along the Underground Railroad, a secret network of brave abolitionists and safe houses where runaway slaves could rest during their journey north to the free states or Canada.

Backstory

She was born Araminta Ross around 1820 in Dorchester County, Maryland, on the plantation where her parents were enslaved. She later took her mother’s name as her own: Harriet. At age five or six, she was “hired out” by her master as a nursemaid for a small baby. She had to stay awake all night so that the baby would not cry and wake the mother. If Harriet fell asleep, the baby’s mother whipped her. Seven years later she was sent to work in the fields.

One day while in her early teens, Harriet was sent to a dry-goods store for supplies. There, she encountered a slave who had left the fields without permission. His overseer was furious, and demanded that she help restrain the young man. She refused, and blocked a doorway to protect the field hand. As the slave ran away, the overseer threw a two-pound weight at him. The weight struck Harriet instead, which she said “broke my skull.”

She believed that her hair – which “had never been combed and… stood out like a bushel basket” – might have saved her life. Bleeding and unconscious, Harriet was returned to her owner’s house and laid on the seat of a loom, where she remained without medical care for two days. She was then sent back to work in the fields, “with blood and sweat rolling down my face until I couldn’t see.”

Shortly thereafter, Harriet began having seizures and would seemingly fall unconscious without warning, although she claimed to be aware of her surroundings while in this state. These episodes were alarming to her family when they were unable to wake her. She also had visions, which she described as divine premonitions. She spoke of “consulting with God,” and trusted that He would always keep her safe. This condition remained with Harriet for the rest of her life.

Escape to the North

Around 1844 Harriet married a free black man named John Tubman and took his last name. In 1849, Harriet wanted to run away, but her husband would not go with her. So she went alone, trekking through the woods at night and following the North Star. During the day she found food and shelter among the free blacks and sympathetic anti-slavery Quakers on the Eastern Shore. She eventually reached freedom in Philadelphia, where she found work as a household servant and saved her money.

On the Underground Railroad

A vast network of people who helped fugitive slaves escape to the North and to Canada, the Underground Railroad was not run by any single organization or person. Rather, it consisted of many individuals – both whites and blacks – who knew only of their local efforts to aid fugitives, not of the overall operation. According to one estimate, the South lost 100,000 slaves between 1810 and 1850.

An organized system to assist runaway slaves seems to have begun towards the end of the 18th century. In 1786 George Washington complained about how one of his runaway slaves was helped by a “society of Quakers, formed for such purposes.” The system grew, and around 1831 it was dubbed The Underground Railroad because of the emerging American railroad system, even using railroad terminlogy: the places where fugitives rested and ate were called stations and were run by stationmasters, and the conductors moved the fugitives from one station to the next.

Sometimes a conductor entered a plantation and then led the runaways northward. The fugitives moved at night, generally traveling between ten and twenty miles to the next station, where they rested and ate, hiding in barns and other out-of-the-way places along the way. While they waited, a message was sent to the next station to alert its stationmaster.

Money was also needed to improve the appearance of the runaways – a black man, woman or child in tattered clothes would invariably attract suspicious eyes. Vigilance committees sprang up in the larger towns and cities of the North, most prominently in New York City, Philadelphia and Boston. These organizations provided food, lodging and money, and helped the fugitives settle into a community by helping them find jobs and providing letters of recommendation.

After hearing that her niece and children would soon be sold, Harriet Tubman arranged to meet them in Baltimore and usher them North to freedom. The following year she returned to the Eastern Shore, the very place where she had suffered through the horrors of slavery, and escorted her sister and her sister’s two children to freedom. This was the first of some nineteen trips during which Tubman guided dozens of people to freedom along the Underground Railroad.

She made her second dangerous trip back to Maryland soon thereafter to rescue her brother and two other men. On her third return, she went for her husband, only to find he had taken another wife and did not want to leave. Undeterred, she found other slaves seeking freedom and escorted them to the North. On one especially harrowing journey she rescued her 70-year-old parents.

Tubman returned to the Eastern Shore again and again throughout the 1850s. She devised clever techniques that helped make sure her trips were successful, including using a master’s horse and buggy for the first leg of the journey; leaving on a Saturday night, since runaway notices could not be placed in newspapers until Monday morning; turning about and heading south if she encountered possible slave hunters; and carrying a drug to silence a baby if its crying might put the fugitives in danger.

In 1850 the dynamics of escaping slavery changed with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law, which stated that escaped slaves could be captured in the North and returned to slavery in the South, leading to the abduction of former slaves and free blacks living in Free States. Law enforcement officials in the North were compelled to aid in the capture of slaves, regardless of their personal principles.

In response to the law, Tubman re-routed the Underground Railroad to Canada, which prohibited slavery. She began relocating fugitives and members of her own family to St. Catharines, Ontario. While there she worked at various jobs and saved her earnings to finance her activities as a Conductor. North Street in St. Catharines remained her base of operations until 1857.

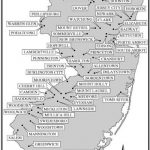

Image: This 28-foot long, 14-foot high bronze statue depicts Harriet Tubman (right) and local conductors Erastus and Sarah Hussey as they lead a group of runaway slaves to safety. Near the Kellogg House in downtown Battle Creek, Michigan, it was designed by sculptor Ed Dwight.

Tubman soon became a legendary conductor on the Underground Railroad. She worked by night in secret, silence and stealth, navigating by the North Star and the light of the moon. She let it be known she carried a gun for protection, but she also used it to threaten the runaways if they became too tired or decided to turn back, telling them, “You’ll be free or die a slave.” She knew that if anyone turned back, it would put her and the others in danger of discovery, capture or death.

By 1856, a $40,000 reward was offered for her capture. On one occasion, she overheard some men reading her wanted poster, which stated that she was illiterate. She promptly grabbed a newspaper and pretended to read it. The ploy worked. The slave catchers never caught her, their most wanted fugitive.

Anti-Slavery Work

Becoming friends with the leading abolitionists of the day, including Quaker minister Lucretia Mott , Tubman lectured at antislavery meetings in the Northeast. She met abolitionists William and Frances Seward of Auburn, New York, which was a hotbed of antislavery activism. Seward was a U.S. Senator and future Secretary of State under President Abraham Lincoln. In 1857, the Sewards provided a home for Tubman, and she seized the opportunity to deliver her parents from the harsh Canadian winters.

In 1859, the Sewards sold the home Tubman and her parents and had been living in along with a small piece of land on the outskirts of Auburn to Tubman, and it became her base of operations when she was not on the road aiding fugitives from slavery or speaking in support of the cause.

Harriet Tubman remained active during the Civil War. Working for the Union Army as a cook, nurse, scout and spy. The first woman to lead an armed expedition in the war, she guided the Combahee River Raid, which liberated more than 700 slaves in South Carolina. During this expedition, Harriet met her future husband, Nelson Davis who was 10 years younger than she.

After the end of the Civil War, Tubman returned to Auburn, New York. In 1869, she married Civil War veteran Nelson Davis, and the couple built a new home near the original house and spent the rest of their lives there. In 1874, they adopted a baby girl named Gertie. During her time in Auburn, Tubman also worked for social reform. especially the women’s rights movement. Auburn was only twelve miles from Seneca Falls, the site of the first Women’s Rights Convention in 1848.

On March 25, 2013, President Barack Obama signed a proclamation creating a Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, where Tubman was born and lived until her escape, and where she returned time after time to lead other slaves to freedom. This is an excerpt from the Presidential Proclamation:

It was in the flat, open fields, marsh and thick woodlands of Dorchester County that Tubman became physically and spiritually strong. Many of the places in which she grew up and worked still remain. Stewart’s Canal at the western edge of this historic area was constructed over 20 years by enslaved and free African Americans. This 8-mile long waterway, completed in the 1830s, connected Parsons Creek and Blackwater River with Tobacco Stick Bay (known today as Madison Bay) and opened up some of Dorchester’s more remote territory for timber and agricultural products to be shipped to Baltimore markets. Tubman lived near here while working for John T. Stewart. The canal, the waterways it opened to the Chesapeake Bay, and the Blackwater River were the means of conveying goods, lumber, and those seeking freedom. And the small ports were places for connecting the enslaved with the world outside the Eastern Shore, places on the path north to freedom….

Further reinforcing the historical significance and integrity of these sites is their proximity to other important sites of Tubman’s life and work. She was born in the heart of this area at Peter’s Neck at the end of Harrisville Road, on the farm of Anthony Thompson. Nearby is the farm that belonged to Edward Brodess, enslaver of Tubman’s mother and her children. The James Cook Home Site is where Tubman was hired out as a child. She remembered the harsh treatment she received here, long afterward recalling that even when ill, she was expected to wade into swamps throughout the cold winter to haul muskrat traps. A few miles from the James Cook Home Site is the Bucktown Crossroads, where a slave overseer hit the 13-year-old Tubman with a heavy iron as she attempted to protect a young fleeing slave….

Tubman and Douglass

It is almost incredible that the best known and most active African Americans of the Civil War era – Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass – were both born into slavery on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, twenty miles apart and within two years of each other. Tubman once brought a group of eleven runaway slaves to Douglass’ home in Rochester, New York. He wrote, “It was the largest number I ever had at any one time, and I had some difficulty in providing so many with food and shelter….”

It is appropriate then that the great abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass should have the last word about Harriet Tubman. This is an excerpt from a letter he wrote to her in 1868:

The difference between us is very marked. Most that I have done and suffered in the service of our cause has been in public, and I have received much encouragement at every step of the way. You, on the other hand, have labored in a private way. I have wrought in the day – you in the night. I have had the applause of the crowd and the satisfaction that comes of being approved by the multitude, while the most that you have done has been witnessed by a few trembling, scarred, and foot-sore bondmen and women, whom you have led out of the house of bondage, and whose heartfelt, “God bless you,” has been your only reward. The midnight sky and the silent stars have been the witnesses of your devotion to freedom and of your heroism.

Excepting John Brown – of sacred memory – I know of no one who has willingly encountered more perils and hardships to serve our enslaved people than you have. Much that you have done would seem improbable to those who do not know you as I know you. It is to me a great pleasure and a great privilege to bear testimony for your character and your works, and to say to those to whom you may come, that I regard you in every way truthful and trustworthy.

SOURCES

PBS.org: Harriet Tubman

About.com: Harriet Tubman

PBS.org: The Underground Railroad

Presidential Proclamation: Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument