Pioneer Women in the American Legal Profession

Though women lawyers did not enter the legal profession until after the Civil War, that does not mean that women did not want to become lawyers in the antebellum period. It only means that there were no records kept.

Though women lawyers did not enter the legal profession until after the Civil War, that does not mean that women did not want to become lawyers in the antebellum period. It only means that there were no records kept.

First, women were denied admission to law schools, and then they were denied permission to practice law. Either the legislature or the supreme court of each state determined the requirements for admission to the state bar, and as a rule they were not keen on changing the status quo.

The entrance of American women into the practice of law formally began in 1869 when Arabella Mansfield was admitted to the Iowa bar. She was allowed to take the bar exam after a liberal Justice included women in the meaning of white male person – by a novel interpretation of a law which stated that masculine words may include females.

The barrier of race was broken in 1872 by Charlotte Ray, the first African American woman and the third American woman of any race to earn a law degree. Ray was also the first woman to graduate from the Howard University School of Law, and became the first African American woman lawyer when she passed the exam was admitted to the District of Columbia bar.

In 1879, Belva Lockwood became the first woman admitted to the bar of the U.S. Supreme Court when she pursuaded Congress to open the federal courts to women lawyers, and the first woman to argue a case before the Supreme Court. When she tried to gain admission to the bar in Maryland, a judge told her that God Himself had determined that women were not equal to men and never could be. When she tried to respond, he had her removed from the courtroom.

Ada Kepley

Henry Kepley trained his wife Ada to be his legal assistant, and with his encouragement, she soon aspired to a professional legal career of her own. Ada Kepley graduated with honors from Union College of Law (now Northwestern) in Chicago in 1870, becoming the first woman to graduate from law school in the United States, but she was denied the right to practice law in Illinois. Henry Kepley helped Ada challenge this ruling by drafting a bill forbidding sexual discrimination in the legal and other professions.

Ada Kepley later wrote:

It seems I was the first woman to graduate from a law school in the world, and in addition, America, which boasted to the rest of the world to be “the land of the free and home of the brave,” gave no freedom to her women… I work as hard as a man, I earn money like a man… I am robbed as a woman! I have no voice in anything or in saying how my money, which I have earned, shall be spent. The men of Illinois and the United States run their hands into my pockets, take out my hard earned money, and say impertinently, “What are you going to do about it…[?]”

Although her husband’s anti-discrimination bill was passed and became law in 1872, Ada did not apply for her license right away. By then her energies had been diverted to social reform; temperance work was her passion and her true legacy. She was the Prohibition Party candidate for Illinois State Attorney General in 1881. Although she had no chance of winning, she used her candidacy to promote women’s right to vote and hold public office.

Ada Kepley did not re-apply for her license to practice law in Illinois in 1881, after which she worked alongside her husband in his Effingham, Illinois office. She also belonged to a number of women’s organizations, notably the Equity Club, a correspondence network which between 1886 and 1890 supported women pioneering in the legal profession.

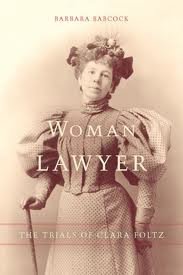

Clara Foltz

In 1878, Clara Shortridge Foltz began her quest to become California’s first woman lawyer. A mother of five small children abandoned by her husband, Foltz turned to the law “[n]ot from ambition and defiance of the norms of womanly conduct, but out of desperation,” in order to support her family. She applied to the Hastings College of Law at the state university, but was turned away with the now famous remark: “…it’s a well known fact that the rustling of a woman’s skirts distracts the minds of male students.”

Rather than challenge the California law limiting bar admission to “white male citizens” in the courts, as Arabella Mansfield had done, Foltz paved the way for her legal career by successfully securing the passage of the Woman Lawyer’s Bill, allowing admission to “any citizen or person.” This law was one of the earliest American statutes allowing women to practice law. Later that year, Foltz passed the California bar exam and became the first woman lawyer on the Pacific Coast.

Foltz was an outspoken woman who used humor as a shield and a sword in dealing with the slights and exclusions as she battled her way to recognition in the male-dominated world of the law. She once responded to a trial opponent’s ridicule by saying:

Counsel intimates with a curl on his lip that I am called the lady lawyer. I am sorry I cannot return the compliment, but I cannot. I never heard anybody call him any kind of a lawyer at all.

In her career of more than 50 years, Foltz was the author of California’s parole law, and the law providing for public defenders. She caused enactment of laws that permitted married women to serve as executors of estates, banned the use of iron cages for transport of prisoners to court, required the separation of juvenile and adult prisoners in jails, and also required seats for shop girls working behind counters.

Quote from Barbara Allen Babcock’s article, Clara Shortridge Foltz: ‘First Woman’

She could read law as an apprentice, but not in the fancy, uptown firm of San Jose’s preeminent practitioner; she could pass a rigorous examination, but not be admitted to California’s first law school; she could become a great trial attorney and still face the constant charge that her very presence in the courtroom would skew the processes of justice.

Clara Foltz ran a thriving private practice that spanned an amazing fifty years. Later in her career, she drafted a bill that would create a public defender system, which was adopted by 30 states. Foltz herself served as a public defender from 1893-1934. Famous in her time as a jury lawyer, public intellectual, leader of the women’s movement and legal reformer, Foltz has been largely forgotten until recently.

Lavinia Goodell

Wisconsin’s first female lawyer, Lavinia Goodell first expressed an interest in the law in 1858, the year she graduated from a ladies’ seminary. Because no law firm would take her under its wing, Goodell began to study law on her own, gradually making a place for herself as a copyist in the firm of Jackson and Norcross. Her dedication to her studies won over one of the firm’s partners, Pliny Norcross, who helped her win admission to the Rock County bar in 1874.

Admission to the Wisconsin bar came by order of a judge after the applicant’s legal knowledge and moral character had been thoroughly examined. While Circuit Judge Herman Conger had his doubts about Goodell based on her gender, he could find no legal reason to deny her admission. Goodell began her private practice and was soon hired by a group of temperance women to prosecute two liquor dealers. Her impressive performance led women’s groups throughout Wisconsin to hire her.

When Goodell appealed a case to the State Supreme Court her gender became an issue. The Supreme Court customarily granted the right to practice before it upon admission to any circuit court bar, but Goodell’s petition was denied in February of 1876. Writing for the court, Chief Justice Edward G. Ryan expressed his outrage at her petition and stated his opinion as to why women were not suited to practice law:

So we find no statutory authority for the admission of females to the bar of any court of this state… We cannot but think the common law wise in excluding women… The law of nature destines and qualifies the female sex for the bearing and nurture of the children of our race and for the custody of the homes of the world and their maintenance in love and honor. And all lifelong callings of women inconsistent with these radical and sacred duties of their sex, as is the profession of the law, are departures from the order of nature; and when voluntary, treason against it…

Shortly thereafter one of Goodell’s staunchest supporters, Speaker of the State Assembly John Cassoday, introduced a bill explicitly allowing women to be admitted to the bar. The bill passed and became law on March 22, 1877. Two years later, in 1879, Goodell renewed her application to the Supreme Court and was admitted over the protests of Justice Ryan.

Sarah Kilgore

Like Ada Kepley, Sarah Killgore began law school at the Union College of Law (now Northwestern) in Chicago in 1869. She then entered the law department at the University of Michigan and graduated in March 1871. Sarah’s reason for going to law school, which she began at age 26, appears to be dissatisfaction with her first career, teaching.

Sarah Kilgore was the first woman to graduate from the University of Michigan Law School, and the first woman admitted to the Michigan bar. Others preceded her in entering law school, graduating from law school or being admitted to the bar, but Kilgore was the first to accomplish all three. She was born in Jefferson, Indiana, where her father was a prominent attorney, and he encouraged her to study law.

She married Jackson Wertman, an attorney in Indianapolis, on June 16, 1875. However, she could not practice law there because the Indiana statute required for admission to the bar “male citizens of good moral character,” so she did office work, specializing in real estate law while her husband handled public court appearances.

In November 1878, the Wertmans moved to Ashland, Ohio, where Sarah bore two chldren who survived infancy. Sarah stayed home to raise her children, but when her son and daughter were in their teens she returned to the law. In September 1893, she passed the required exam and was admitted to the bar in Ohio, returning to her husband’s law office to practice real estate law and the business of abstracting.

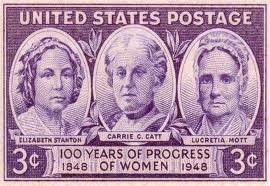

Myra Bradwell

A schoolteacher from Vermont, Myra married James Bradwell, a lawyer. She began to study law in her husband’s Chicago office, intending to assist him in his law practice. As her studies progressed, she decided to become a licensed attorney. This quest was interrupted temporarily by the Civil War, during which Bradwell worked for passage of laws granting women fair property rights, the right to serve on juries and admission to university law departments.

Bradwell also served as Secretary of the Illinois Women’s Suffrage Association, whose goal it was to ensure that Illinois would become the first state to permit women to vote. Through all the turmoil, she steadfastly worked toward her goal of becoming an attorney. In 1869, she passed a rigorous examination and applied for admission to the state bar. Had this been permitted, she should have been one of the first two women lawyers in the United States (along with Arabella Mansfield).

However, the Illinois State Supreme Court denied her application, ruling that her ‘married condition’ impaired her ability to keep a client’s confidence. Bradwell immediately requested the Court to reconsider, however, the Chief Justice harshly affirmed the original denial: not only was Bradwell’s admission to the bar denied because she was a married women, it was denied because she was a woman. The Court reasoned that women might have a detrimental effect upon the administration of justice.

Bradwell promptly filed a writ of error to the United States Supreme Court, which affirmed the Illinois court’s ruling by noting that even ‘the law of the Creator’ had placed limits on the functions of womanhood. Bradwell made no subsequent attempts to attain admission to the bar. Why would she willingly subject herself to an endless barrage of opposition and ridicule, only to give up the fight so easily?

It has been suggested that the goal of America’s first woman lawyer went far beyond her own ambitions – that her fight for admission to the bar was a deliberate test case (Bradwell v. Illinois, 1873) to open the door to other women lawyers and broaden the struggle for women’s rights. For the remainder of her life Bradwell devoted her time to legal reform, women’s rights and encouraging other aspiring female attorneys.

As she lay dying of cancer, James Bradwell secretly convinced the Illinois Supreme Court to admit his wife to the state bar, antedating her admission to 1869, the date of her original application. Two years later the United States Supreme Court followed suit. Just months before her death in 1894, the Illinois Bar Association called her the pioneer woman lawyer, because she had blazed a trail for others to follow.

SOURCES

Clara Shortridge Foltz: ‘First Woman’

History: First Women Lawyers in Illinois

Wisconsin Historical Society: Lavinia Goodell

Barred from the Bar – A History of Women and the Legal Profession

Centennial of the National Association of Women Lawyers: The First 50 Years – PDF File