Women Spies for the Union

Image: Illustration of Sarah Emma Edmonds on horseback dodging a bullet fired by a southern woman.

Image: Illustration of Sarah Emma Edmonds on horseback dodging a bullet fired by a southern woman.

American society was still quite Victorian in many ways during the 1860s. Therefore, women spies were not as likely to be roughly interrogated or hanged when their true identity was discovered. These heroines exhibited great courage and were willing to suffer imprisonment or death in the service of their country.

Elizabeth Van Lew

From a wealthy family well-known in Richmond society, Elizabeth Van Lew was educated in Philadelphia and returned home an ardent abolitionist. Elizabeth was in her forties when the War began, and steadfastly loyal to the Union. She started writing to Federal officials to tell them about the “seccession mania” occurring in Richmond, but she was soon sending information about Confederate troop locations, numbers and movements. Once regular mail was no longer safe, she recruited her servants as her messengers.

Late in 1863, General Benjamin Butler recruited Van Lew as a spy ad gave her a simple cipher system to use in her reports. She kept the cipher key in the case of her watch. She hid the secret messages hollowed out egg shells hidden among real eggs or in the shoes of her African American servants, who then relayed the notes to Union officers through several helpers and agents.

Butler passed on to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton a sample of the quality of the information he had been getting “from a lady in Richmond.” She told where new artillery batteries were being set up, reported that three cavalry regiments had been “disbanded by General Lee for want of horses,” and revealed that the Confederacy “intended to remove to Georgia very soon all the Federal prisoners.”

By June 1864, the Richmond underground had five ‘depots,’ where couriers could deliver their reports for pickup by Union operatives slipping through Confederate lines. One of those was the Van Lew family farm just outside Richmond, where Van Lew was running more than a dozen operatives, including a baker who used his delivery wagon as a cover for picking up and relaying reports.

Unlike those of her Confederate counterparts, Elizabeth Van Lew’s journal was never intended for publication. She kept it “buried for safety” in the backyard of her Richmond home throughout the war and it was not found until after her death. Many sections had been cut out, apparently to protect people who worked with her in her spy operations. It contained contained cautious references to her work for the Union:

Written only to be burnt was the fate of almost everything which would not be of value. Keeping one’s house in order for Government inspection with Salisbury prison [a Confederate prison in North Carolina] in prospective, necessitated this. I always went to bed at night with anything dangerous on paper beside me, so as to be able to destroy it in a moment.

The threats, the scowls, the frowns of an infuriated community – who can write of them? I have had brave men shake their fingers in my face and say terrible things… I have turned to speak to a friend and found a detective at my elbow. Strange faces could be seen peeping around the columns and pillars of the back portico… I shall ever remember the pale face of this dear lady [her mother]… for her arrest was constantly spoken of, and frequently reported on the street, and some never hesitated to say she should be hanged.

After the war, Van Lew asked the War Department for all of her dispatches, which she destroyed to protect her network of spies and agents from postwar retribution. In her journal, she noted that she was called a traitor in the South and a spy in the North; she said she preferred “the honored name of ‘Faithful’ because of my loyalty to my country.”

Mary Elizabeth Bowser

After the war began, Elizabeth Van Lew asked her African American servant Mary Elizabeth Bowser to serve in the elaborate spying system Van Lew had established in Richmond. Van Lew asked a friend take Mary along to help at functions held at the Confederate White House by Varina Davis, the wife of Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

To gain access to top secret information, Mary took on the role of Ellen Bond, a dim-witted, but able servant. With the racial prejudice of the day, the assumption that slaves were ignorant and, and the way slave servants were trained to seem invisible, Bowser was able to glean considerable information simply by doing her job. While serving meals and cleaning up afterward, she overhead many conversations between the president and his cabinet members and military officers. Mary proved herself and began to work full-time at the Confederate White House.

Bowser had a photographic memory, allowing her to retain all of the letters and documents that were left out in the president’s private study, and later commit them to paper, word for word. She sometimes passed the information she had gathered to Van Lew, meeting her after dark near the Van Lew farm, just outside of Richmond.

Bowser also worked with Thomas McNiven, a Richmond baker. With his business, both at the bakery itself and while making deliveries, he was able to receive and pass on secret messages without suspicion. Just before his death in 1904, McNiven told his daughter Jeannette about his spy activities, and that Mary Elizabeth Bowser was the source of the most crucial information:

“…as she was working right in the Davis home and had a photographic mind. Everything she saw on the Rebel president’s desk, she could repeat word for word. Unlike most colored, she could read and write. She made a point of always coming out to my wagon when I made deliveries at the Davis’ home to drop information.”

Apparently President Davis came to realize there was a leak in the house, and suspicion eventually fell on Bowser late in the war. She fled in January 1865, but attempted one last act as a Union spy and sympathizer by burning down the Confederate White House, but was unsuccessful.

In 1995, Mary Elizabeth Bowser was inducted into the United States Army Military Intelligence Corps Hall of Fame where she was noted as “one of the highest placed and most productive espionage agents of the war.”

Kate Warne

The first female detective in the United States, Kate Warne [link] was already working for master Union spy Allan Pinkerton before the Civil War began. Kate was one of five agents sent to Baltimore, Maryland on February 3, 1861 to investigate the secessionist activity occurring there. During that investigation, she unveiled evidence of a plot to assassinate president-elect Abraham Lincoln on the way to his inauguration.

Posing as a rich southern lady with a thick accent, Warne tracked suspicious movements among Baltimore secessionists. She infiltrated secessionist social gatherings in the area, posing as a flirting “southern belle” and was quick to not only verify that there was a plot to assassinate Lincoln, she learned details of the intended operation.

Lincoln was planning to travel from his home Springfield, Illinois to Washington, DC by train with stops at major cities along the way, including Baltimore. Due to the configuration of the train system in Baltimore, all southbound trains had to transfer to another track about a mile away. The attempt on Lincoln’s life was to take place in the railway station as he changed trains.

Kate Warne was a key player in the foiled Baltimore assassination plot. Not only did she help to uncover details of the plot, but she also carried out most of the arrangements to smuggle Lincoln into Washington, DC in the dark of night. With the clothing Warne provided – a traveling suit, a soft felt cap and a shawl draped over one arm – Lincoln played the role of an invalid.

Warne secured the necessary four berths on a train leaving Philadelphia under the pretext that they were for her sick brother and family members. The train pulled out shortly before 11 p.m. and arrived in Baltimore about 3:30 a.m. on February 23. The sleeping cars with Lincoln on board arrived in Washington around 6 a.m. Lincoln made it to the capital without being recognized and was inaugurated on March 4, 1861.

Kate Warne closely guarded the president-elect and did not sleep a wink that night. It has been suggested that Allan Pinkerton came up with the slogan for his agency – we never sleep – as a result of Warne’s vigilance that night.

Sarah Emma Edmonds

At the outbreak of the Civil War Sarah Emma Edmonds disguised herself as a man and enlisted in the Union army under the name Frank Thompson. While stationed in Virginia at the beginning of the Peninsular campaign, Edmonds volunteered for a mission inside Rebel lines at Yorktown.

Edmonds decided to infiltrate Rebel lines disguised as a black man. She bought clothing from a fugitive slave, obtained a minstrel wig to cover her hair, and colored her face, hands and arms with silver nitrate. She slipped past Rebel pickets at night and the next morning joined slaves who were returning to Yorktown after taking breakfast to the pickets.

At Yorktown Edmonds and the slaves were put to work with picks and shovels on fortifications. After a day of hard labor, Edmonds recorded that her hands were “blistered from my wrists to the finger ends.” That evening, Edmonds talked one of the slaves into exchanging duties with her. For the next two days she carried buckets of water around the camp, a job that enabled her to gather intelligence about the fortification and its armament. She even caught a glimpse of General Robert E. Lee and General Joseph E. Johnston.

The evening of her third day inside Rebel lines, Edmonds was sent with her group of slaves to carry supper to the picket lines, where she was surprised to find that some of the pickets were African American men. As she was talking to one of the black pickets, an officer came up, gave her a gun, and ordered her to take the place of a picket who had recently been shot. She slipped away during the night and returned to the Union lines with information about the Confederate fortifications. Over the coming year, Edmonds would make numerous forays into enemy territory.

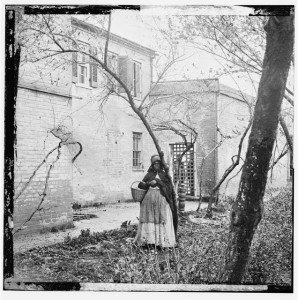

Harriet Tubman

At the request of the federal government, former slave and conductor on the Underground Railroad, Harriet Tubman served with the Union Army in South Carolina, as a scout, spy, nurse and soldier. Under the command of Colonel James Montgomery, Tubman led the Combahee River Expedition with men from the African American 2nd South Carolina regiment. The object of the raid was to take up the torpedoes placed by the rebels in the river, to destroy railroads and bridges, and to cut off supplies from the rebel troops.

On June 1, 1863, three small gunboats set out on the Combahee River to begin the mission, relying on information Harriet and her scouts had received from their sources about Confederate positions. They destroyed houses, mills and outbuildings along the way and took the Confederate stores of rice and cotton, as well as potatoes, corn and livestock, and left the plantations as smoking ruins.

Slaves working in the fields were wary when they first saw the approaching Union ships and troops, but word spread quickly that the forces were there to liberate them. Many slaves ran to the riverbank and begged to be taken on board the ships, despite the efforts of overseers and Confederate soldiers to stop them. Hundreds of slaves stood on the shore and, when the small boats put out to get them, they all wanted to get in at once.

After the boats were filled to capacity and beyond, the throng of escaping slaves still ashore held on to the boats to prevent them from leaving. Oarsmen tried beating them on their hands, but the mob would not let go, as they were afraid the gunboats would go off and leave them. The small boats made several trips back and forth to load those who wanted to leave.

The next day, the Union ships returned to Beaufort, where the newly freed slaves were transported to a resettlement camp on St. Helena Island, one of the Sea Islands off the coast of South Carolina. Due to the efforts in planning and intelligence provided by Tubman and her contacts, more than 750 slaves were freed as a result of Montgomery’s raid. Many of the freedmen joined the Union Army.

The pro-Union Commonwealth newspaper reported:

Colonel Montgomery and his gallant bank of 300 black soldiers under the guidance of a black woman, dashed into the enemy’s country, struck a bold and effective blow, destroying millions of dollars worth of commissary stores, cotton and lordly dwellings, and striking terror into the heart of rebeldom, brought off nearly 800 slaves and thousands of dollars worth of property, without losing a man or receiving a scratch.

It was a glorious consummation… The colonel was followed by a speech from the black woman who led the raid and under whose inspiration it was originated and conducted. For sound sense and real native eloquence her address would do honor to any man, and it created a great sensation.

Pauline Cushman

When the Civil War began Pauline Cushman was a struggling thirty-year-old actress who had toured the United States for years in a variety of different plays. In 1863, while performing in Louisville, Kentucky, she was offered money to toast Jefferson Davis during a performance. Cushman contacted a Union official and offered to perform the toast as a way to ingratiate herself to the Confederates so that she could spy for the Union. The official agreed, and she gave the toast the next evening.

While operating in Middle Tennessee after the Battle of Stones River, Cushman came under suspicion because of her constant travel between Shelbyville, Wartrace, Manchester and Tullahoma. Cavalrymen under General John Hunt Morgan captured her and turned her over to General Nathan Bedford Forrest. Based upon documents found on her person, Cushman was found guilty of espionage and sentenced to be hanged.

However, the local Confederates were occupied with defending themselves against an assault, and seemed to be in no hurry to hang her. When they left the area, they simply left her behind. She headed to the safety of the Federal lines at Nashville. Because of the attention she received, Cushman’s short career as a spy came to an abrupt end. After the war she toured the country dressed in uniform lecturing about her exploits as a spy.

Epilogue

As the Civil War unfolded, there was a major shift in the way women operatives were viewed and utilized. At the beginning, women were considered innocent and non-threatening, but that slowly changed as officials began to understand the immense value of women operatives. Because of the information they routinely provided and the harsh conditions under which they worked, political and military leaders began to appreciate their contributions.

This changing perception of women spies made Civil War intelligence gathering much more dangerous for females, especially those working undercover. Perhaps the most effective women spies were those we will never know. After the war, documents were destroyed, identities were protected, and they are lost to history.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Kate Warne

Intelligence Collection – The North

Wikipedia: Raid at Combahee Ferry

Women in History: Mary Elizabeth Bowser

Sarah Emma Edmonds: Spy Disguised As A Slave