Daughter of Union General Ulysses S. Grant

Nellie Grant was the third child and only daughter of Union general and later president and first lady, Ulysses S. Grant and Julia Dent Grant. Grant was an affectionate father and his devotion to Nellie was touching to all who observed it. Nellie was only thirteen when she moved into the White House, and the press adored her.

Nellie Grant was the third child and only daughter of Union general and later president and first lady, Ulysses S. Grant and Julia Dent Grant. Grant was an affectionate father and his devotion to Nellie was touching to all who observed it. Nellie was only thirteen when she moved into the White House, and the press adored her.

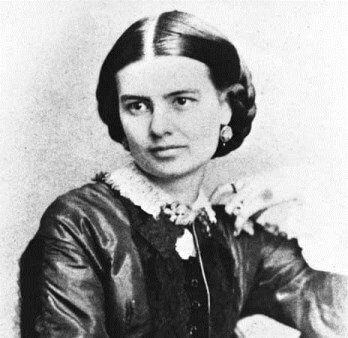

Image: Nellie at age 15

Early Years

Nellie Grant was born on the Fourth of July in 1855 at White Haven, her mother’s family home near St. Louis, Missouri. She was first named Julia, at the insistence of her father, but was christened Ellen Wrenshall Grant at eighteen months to honor her dying grandmother. She was thirteen when her father was elected president and the family moved into the White House.

Her parents believed Nellie should be properly educated, and they chose Miss Porter’s School in Connecticut. Her father escorted her to Connecticut, because he believed that his wife would be unable to withstand Nellie’s pleas to come back home. By the time Grant arrived back in Washington, DC, she had sent three telegrams expressing her homesickness, and he sent an escort to bring her back home.

By age fifteen, she was a guest at the exclusive parties thrown by Washington’s elite. Some people thought the President’s daughter was spending too much time staying out late at social events. The Grants ignored those rumors, but soon became concerned about the many young suitors who pursuing Nellie.

In 1872, the Grants decided to enhance Nellie’s education by sending her on a grand tour of

Europe’s historic cities, which was considered a must for any respectable young woman in the late nineteenth century. When they learned that an old family friend was planning a trip to Europe with his family, the president requested that they take Nellie along.

In Europe, Nellie was received as American royalty. Although the trip was designed to broaden her education and expose her to high European culture, she could not escape the balls and garden parties given in her honor. Wherever she went she was invited to the biggest social events of the season, and was showered with gifts and attention.

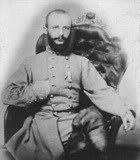

When the summer came to a close, passage for Nellie’s return trip to America was booked aboard the luxurious steamship Russia. On board, Nellie met Algernon Sartoris, a handsome wealthy English singer, son of opera singer Adelaide Kemble and nephew of the famous actress Fanny Kemble. With her seasick chaperones confined to their cabins, Nellie spent much of her time with Sartoris. She had just turned 17, and he was almost 22 years old.

At that time, Algy, as he was called, was serving as a British officer newly assigned to the British delegation in Washington, DC. During the voyage to New York Algernon and Nellie fell madly in love. According to her mother, Nellie returned a changed girl. Julia Grant wrote in her memoirs that Nellie was “no longer a nestling, but a young woman equipped and ready for the battle of life.”

The young lovers agreed to wait to announce their engagement for a year at the insistence of President and Mrs. Grant, who were not impressed with Nellie’s groom-to-be. At first glance, he appeared to be a dashing young officer with a bright future, but despite his youth, he was struggling with alcoholism. He could be arrogant, boastful, crude and obnoxious, but he could also be quite charming.

The President and the First Lady were concerned for their daughter’s future, but Nellie was unmoved by their entreaties. All they could convince her to do was hold off on the wedding for a year. Nellie and Algy conducted their courtship by correspondence, exchanging letters through the spring of the following year. By the summer of 1873, it became apparent that their relationship was quite serious, and it caught the attention of the president.

U. S. Grant was not thrilled at the prospect of his only daughter marrying a British subject. The thought of her leaving the family was bad enough, but to have her leave the country as well was unbearable. Grant did what he could to prevent the marriage between Nellie and Sartoris. He wrote a letter in July 1873 to Nellie’s future father-in-law, Algernon Sartoris, Sr., in which he tried to ascertain whether Algy had a past with women and whether he was likely to remain in England. Grant wrote:

Much to my astonishment, an attachment seems to have sprung up between these two young people… I had only looked upon my daughter as a child, with a good home which I did not think of her wishing to quit for years yet. She is my only daughter and I therefore feel a double interest in her welfare… I hope you will attribute any apparent bluntness to a father’s anxiety for the welfare and happiness of an only and much loved daughter.

Everyone who knew Grant recognized that Nellie was his favorite child. His wife admitted it in her memoirs, as did his sons in later interviews. An example of Grant’s affection appeared in the August 17, 1873 issue of the Portsmouth Ledger, as the Grants passed through New Hampshire. A reporter onboard a train as the President traveled to Augusta wrote:

President Grant arrived on the new Pullman car Mystic with the usual dignitaries and his children. Miss Nellie Grant… who is 17 years old, held her father’s hand throughout the journey. When a baggage handler became too inquisitive towards the fair daughter, the General showed positive annoyance and held Miss Grant ever-closer to the Presidential bosom.

Marriage and Family

Despite her father’s disapproval, Nellie married Algernon Sartoris in a lavish White House ceremony in the East Room on May 21, 1874. Though less than two hundred guests witnessed the wedding, it was the subject of endless public fascination. The bride wore a $2,000 white satin gown trimmed in Brussels lace, and entered the room on the arm of her father, who stared resolutely at the floor. After the wedding he was found sobbing in Nellie’s room.

A few months later, Nellie and Algy Sartoris moved to England, and Nellie saw little of her parents during the time she lived there. The Sartoris marriage seemed to progress well enough at first. The couple moved into a cottage on the Sartoris family estate. Nellie gave birth to four children in quick succession: Grant Grenville Edward (1875-1876), Algernon Edward (1877-1907), Vivien May (1879-1933) and Rosemary Alice Sartoris (1880-1914).

On both sides of the Atlantic, rumors were circulating about the Sartoris marriage. Algy was an alcoholic and a gambler, and was often absent from the couple’s home. In 1877, Ulysses and Julia Grant left the White House and shortly thereafter toured Europe. They visited their daughter and grandchildren but stayed only a week before continuing their trip.

Algy was drinking more heavily and appeared bored with Nellie. Any hopes he might have had of gaining in stature from his union with the daughter of the president of the United States had not materialized. When President and Mrs. Grant returned home to New Jersey in 1879, they issued a statement meant to dispel any more gossip about Nellie’s marriage.

Problems within the Sartoris marriage were aggravated by Algy’s continuing inability to handle his liquor, and beginning in the 1880s, his very public appearances in Europe and the United States with females who were not his wife. Sartoris also proved to be a disappointment to his own parents, who made it clear that they did not blame Nellie for the failure of the marriage.

By some accounts, Nellie asked Algy for a divorce and he refused. Other accounts assert that Nellie and Algernon were, in fact, divorced prior to 1893. Nellie lived for years in London’s fashionable West End, both with and without her scoundrel husband. They also had homes in Canada, Wisconsin and Washington, DC.

Coming Home

In May 1884 Ulysses S. Grant was defrauded of his entire fortune in a Wall Street swindle. In October 1884 he was diagnosed with throat cancer. Nellie was still living in England with her children, but he wanted her by his side. Suffering intense agony from his illness, Grant wrote Nellie a touching letter on February 16, 1885:

Dear Nellie,

Your letter of the second of February, to your mother, came two or three days ago. Algy arrived a few days before and came up and stayed with us until after dinner. All the family are well except me. The sore throat which you recollect I had all the time we were at Long Branch last summer has proven to be a very serious matter. I paid no attention to it until it had been four months. I found then the doctors considered it a very serious matter. Even now I have to see them twice a day.It has troubled me so much to swallow that I have fallen off nearly 30 pounds. It has only been within the last two days that the doctors have been willing to say that the ulcers in my throat are beginning to yield to treatment. It will be a long time yet before I can possibly recover.

It be would be very hard for me to be confined to the house so long a time if it was not that I have become interested in the work which I have undertaken. It will take several months yet to complete the history of my campaigns [Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant]. The indication now are that the book will be in two volumes of about 450 pages each. I give a biography of my life up to the breaking out of the Rebellion. If you ever take the time to read it you will find out what sort of a boy and man I was before you knew me.

I do not know whether my book will be interesting to other people or not, but all the publishers want to get it, and I have had larger offers than have ever been made for a book before. Fred [Grant’s son] helps me greatly in my work. He does all the copying and looks up references for me. We have all been as happy as could be expected considering our great losses and my personal suffering. Philosophers profess to believe that what is for the best. I hope it may prove so with our family.

All join me in sending love and kisses to you and all the children.

Your affectionate Papa

Though he did not implicitly ask her to come home, Nellie undoubtedly got the message – she arrived in New York 16 days later. Considering that the crossing of the Atlantic ocean took seven days and mail delivery was not the best at that time, she must have left England as soon as she received the letter. Despite his condition, Grant met his daughter at the dock, embracing her with tear streaked eyes.

Grant’s Memoirs

During the last months of his life Grant raced against the clock to write a two-volume memoirs that would give his family financial security after his death. In constant pain as the tumor on the side of his throat grew ever larger, Grant continued to write despite being plagued by hemorrhages, strangulation and exhaustion. When the disease took his voice and he could no longer dictate, he resorted to pen and paper.

Image: Grant spent his last days on his porch with pencil and paper, wrapped in blankets and in horrible pain, trying desperately to finish his memoirs.

Image: Grant spent his last days on his porch with pencil and paper, wrapped in blankets and in horrible pain, trying desperately to finish his memoirs.

Grant had originally intended to publish his memoirs with Robert Underwood Johnson (of the writing team Buel and Johnson), but Mark Twain made Grant a better offer. However, he remained on good terms with Johnson and wrote four Civil War articles for his magazine during the last year of his life in addition to working on his book. Johnson visited Grant shortly before his death, and later wrote:

I could hardly keep back the tears as I made my farewell to the great soldier who saved the Union for all its people and to the man of warm and courageous heart who had fought his last long battle for those he so tenderly loved.

Three days after finishing his memoirs, and months after his doctors thought he could not live another day, Ulysses S. Grant died on July 23, 1885 at age 63. Nellie returned to England to be with her children; they had not been allowed to travel to America with her.

While living in a hotel in Europe in 1893, Algernon Sartoris died of pneumonia at age 42. When word reached the United States, newspapers reported the story of his death with no mercy for the man who had abused their favorite daughter. Of Algy’s death, the St. Louis Republic wrote:

The death of Algernon Sartoris, the husband of Nellie Grant, at Capri, Italy, created no other feeling here than of complacency. Sartoris was one of the most unpopular men who ever came to this country, and he probably left more enemies when he returned to Europe than any foreigner before or since that time.

After Algy’s death, Nellie remained in England until the autumn of 1894, when she returned to America with her children and took up residence in Washington, DC.

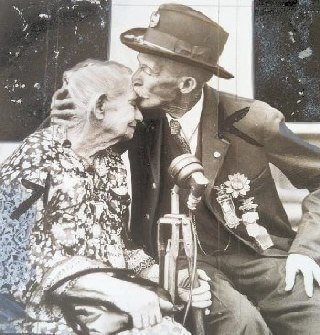

Eighteen years after Algy’s death, Nellie married Frank Hatch Jones. Sadly, circumstances did not allow her to fully enjoy her second marriage. The couple moved to Chicago, Illinois, where Nellie suffered a disabling stroke. Paralyzed, she remained an invalid until her death in 1922.

After announcing their engagement on June 21, 1912, Nellie married childhood friend Frank Hatch Jones on July 4, 1912 – her 57th birthday. Hatch was a lawyer, Yale University graduate, Member and Chairman of the Sangamon County Democratic Committee, President of the State League of Democratic Clubs of Illinois and Secretary of the Illinois State Bar Association.

However, Nellie’s happiness was short-lived. Three months after the wedding, she suffered a stroke and remained an invalid for the last ten years of her life. She also outlived all of her children except daughter Vivien May.

Nellie Grant Sartoris Jones died August 30, 1922 in Chicago, Illinois, and was buried in Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield, Illinois.

Nellie Grant’s White House wedding had captured the attention of an American public who were eager to focus on something positive in the bleak years following the Civil War and Reconstruction. The tragic circumstances of the marriage did not succeed in tarnishing the memories of that happy occasion, and it still remains as one of the great events in the history of the White House.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Nellie Grant

A White House Wedding – PDF File

Ulysses S. Grant Homepage: Nellie Grant

Nellie Grant and Algernon Sartoris Marriage Profile