Advocate for the Rights of Married Women

Elizabeth Packard was a social reformer whose experiences in a mental hospital began her quest for protective legislation for the insane and improved married women’s rights. She wrote numerous books and lobbied legislatures literally from coast to coast, advocating more stringent commitment laws, protections for the rights of asylum patients, and laws to give married women equal rights in matters of child custody, property and earnings.

Elizabeth Packard was a social reformer whose experiences in a mental hospital began her quest for protective legislation for the insane and improved married women’s rights. She wrote numerous books and lobbied legislatures literally from coast to coast, advocating more stringent commitment laws, protections for the rights of asylum patients, and laws to give married women equal rights in matters of child custody, property and earnings.

Marriage and Family

Elizabeth Parsons Ware was born on December 28, 1816 in Ware, Massachusetts. At the insistence of her parents, she married minister Theophilus Packard on May 21, 1839. Like many other women of her era, Elizabeth settled into domestic life as a wife and mother in the decades before the Civil War. The couple had six children and led a fairly peaceful life in Kankakee County, Illinois.

But Theophilus Packard was a strict Calvinist minister who held very conservative views about religion. Though she was a religious woman, after many years of marriage Elizabeth found herself at odds with her husband’s teachings. She began to question her husband’s religious beliefs, going so far as to express her own opinions to Reverend Packard’s parishioners in church.

On one occasion, Elizabeth announced in the middle of a service that she was going across the street to worship with the Methodists, whose beliefs were much closer to her own. This ‘defiance’ led Reverend Packard to question his wife’s sanity. In 1860, he arranged for Dr. J.W. Brown – masquerading as a sewing machine salesman – to speak with her.

During their conversation, Elizabeth complained of her husband’s domination and his accusations to others that she was insane. Dr. Brown reported this to Theophilus and he decided to have Elizabeth committed to the Illinois State Hospital for the Insane at Jacksonville, Illinois. She learned of his decision on June 18, 1860, when the county sheriff forcibly removed her from her home and put her on a train to Jacksonville.

Involuntary Commitment

All of this was perfectly legal. When Illinois opened its first hospital for the mentally ill in 1851, the state legislature passed a law that required a public hearing before a person could be committed against his or her will. There was one exception, however: a husband could have his wife committed without either a public hearing or her consent.

The superintendent of the state hospital, Dr. Andrew McFarland, was an intelligent and charming man who at first took a liking to Elizabeth. But when she refused to pretend that she agreed with her husband or to change her religious views as the doctor suggested, he turned against her and had her transferred to the 8th Ward for the violent and hopelessly insane.

Elizabeth Packard spent the next three years at the Jacksonville State Hospital, where she was regularly questioned by her doctors but refused to agree that she was insane or to change her religious views. She managed maintain her sanity while she was there, taking it upon herself to clean the filthy rooms in the 8th ward. To maintain her health, she stuck to a regular routine of physical exercise and good hygiene.

Elizabeth gradually won over most of the staff at the hospital and was even given a set of keys because of the duties she assumed there. She wrote constantly, telling the story of the injustice she was suffering, and collected written testimony from other patients detailing their experiences. Her notes would become the basis for the books she would later write.

When her oldest son turned 21 in 1863, he had legal authority to remove her from the asylum, and convinced his father to agree. But Elizabeth resisted leaving, because she was finishing her book, and was afraid her husband would try to lock her up somewhere else. She was right to worry.

She came home to a dirty and disorganized house, her daughter having been forced to take over the housework and child care at the age of 11. But Elizabeth’s “moral insanity” had not abated in Theophilus’ eyes. He had placed locks on everything, so that Elizabeth could not even get food or clean linen without his permission.

Soon he locked her in the nursery, nailing the windows shut and preventing anyone from seeing her. There she remained for a month and a half – in a room without a fire and without warm clothing. In the meantime he was also trying to have her transferred to another institution. Elizabeth was finally able to throw a letter out the window to a neighbor, and a writ of habeus corpus was issued on her behalf.

Judge Charles Starr ordered Reverend Packard to bring Elizabeth to his chambers on January 12, 1864. Packard produced Elizabeth and a written statement explaining that she “was discharged from [the Illinois State] Asylum without being cured and is incurably insane… [and] the undersigned has allowed her all the liberty compatible with her welfare and safety.” Unimpressed, the judge scheduled a jury trial in Kankakee, Illinois.

Packard v. Packard

The trial of Packard v. Packard began on January 13, 1864. Theophilus Packard claimed that his wife was insane and that he was therefore entitled to confine her at home. His lawyers produced witnesses from his family and church who testified that Elizabeth had argued with her husband and had attempted to leave the church, evidence in their eyes that she was insane.

Dr. J.W. Brown, who had surreptitiously interviewed Elizabeth testified that she had described her husband as wishing that “the despotism of man may prevail over the wife,” but it was during their discussion of religion that he “had not the slightest difficulty in concluding that she was hopelessly insane.”

Elizabeth Packard, Dr. Brown said, “found fault that Mr. Packard would not discuss their points of difference in religion in an open manly way instead of going around and denouncing her as crazy to her friends and to the church. She had a great aversion to being called insane. Before I got through the conversation she exhibited a great dislike to me.”

Abijah Dole, the husband of Reverend Packard’s sister Sybil, testified that he knew Elizabeth had become disoriented because she told him that she no longer wished to live with Reverend Packard. Dole also testified that Elizabeth had requested a letter terminating her membership in her husband’s church. “Was that an indication of insanity?” Elizabeth’s lawyer, John Orr, inquired. Dole replied: “She would not leave the church unless she was insane.”

Sybil Dole also testified against Elizabeth, stating, “She accused Dr. Packard… of depriving her of her rights of conscience – that he would not allow her to think for herself on religious questions because they differed on these topics.” Finally, a certificate from the Illinois State Hospital was read, which stated that she was discharged because she could not be cured. Reverend Packard’s lawyers rested their case.

Elizabeth Packard’s lawyers, Stephen Moore and John Orr, responded by calling witnesses from the neighborhood that knew the Packards but were not members of Theophilus’ church. These witnesses testified they never saw Elizabeth exhibit any signs of insanity, while discussing religion or otherwise.

Sarah Haslett then testified about her friend’s in-home confinement and described the sealed window, “fastened with nails on the inside and two screws passing through the lower part of the upper sash and the upper part of the lower sash from the outside.”

The final witness was Dr. Duncanson, who was both a physician and a theologian. Dr. Duncanson had interviewed Elizabeth Packard and he testified that he had conversed with Mrs. Packard for three hours, and while he was not necessarily in agreement with all her religious beliefs… “I do not call people insane because they differ with me. I pronounce her a sane woman and wish we had a nation of such women.”

On January 18, 1864 the jury reached its verdict in seven minutes. “We, the undersigned, Jurors in the case of Mrs. Elizabeth P.W. Packard, alleged to be insane, having heard the evidence… are satisfied that [she] is sane.” Judge Charles Starr ordered “that Mrs. Elizabeth P.W. Packard be relieved of all restraints incompatible with her condition as a sane woman.”

Elizabeth returned home to find that Reverend Packard had sold their house in Illinois and left for Massachusetts with her money, notes, wardrobe and their young children. His actions were perfectly legal under Illinois and Massachusetts law; Elizabeth Packard had no legal recourse by which to recover her children and property.

Asylum Reform

Though they never divorced, Elizabeth Packard never returned to her husband, but the underlying social principles which had led to her confinement still existed. Packard devoted the rest of her life to social reform, using her experiences to expose the poor state of mental health care. She traveled around the country, calling for legislative changes that gave mental patients more rights.

Despite strong opposition from the psychiatric community, she campaigned to pass laws in Illinois that required a jury trial to prove insanity. Packard’s laws were passed in state after state, laws that had a lasting impact on the commitment and care of the mentally ill in the United States. During her lifetime, many states revised their laws.

Packard founded the Anti-Insane Asylum Society and published several books, including Marital Power Exemplified, or Three Years Imprisonment for Religious Belief (1864), Great Disclosure of Spiritual Wickedness in High Places (1865), The Mystic Key or the Asylum Secret Unlocked (1866) and The Prisoners’ Hidden Life, Or Insane Asylums Unveiled (1868). Through her book sales she became financially independent.

From The Prisoners’ Hidden Life:

The great evil of our present Insane Asylum System lies in the fact that insanity is there treated as a crime, instead of a misfortune, which is indeed a gross act of injustice.

Packard also used the press to great effect. The Illinois State Register wrote about her book Marital Power Exemplified on the front page:

The book is designed to inform the public of the power husbands may assume under the law over their wives. Mrs. Packard designs to bring the subject matter of complaint before the general assembly to the end that relief may be provided other unfortunates who are suffering under similar persecution.

Due to her efforts and the influence of her books, 34 bills were passed in various state legislatures, including a law passed by the Illinois legislature in 1869 which required a jury trial before a person could be committed to an asylum. She also influenced the formation of The National Society for the Protection of the Insane and the Prevention of Insanity in 1880.

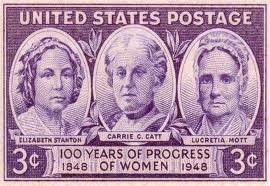

Married Women’s Rights

Elizabeth Packard then turned her efforts to the emancipation of married women. Under the law of Coverture, upon marriage, a woman’s legal rights were subsumed by those of her husband. Coverture was enshrined in the common law of England and the United States throughout most of the 19th century. Judges and lawyers referred to the overall principle as coverture.

Under this law, a married woman was not recognized as having legal rights and obligations distinct from those of her husband in most respects. Instead, through marriage a woman’s existence was incorporated into that of her husband, so that she had very few recognized individual rights of her own. Husband and wife were one person as far as the law was concerned, and that person was the husband.

A married woman could not own property, sign legal documents or enter into a contract, obtain an education against her husband’s wishes, or keep a salary for herself. If a wife was permitted to work, under the laws of coverture she was required to relinquish her wages to her husband. This persisted until the mid-to-late 19th century, when married women’s property acts began to be passed.

Elizabeth Packard wrote, lectured and lobbied on these issues and was instrumental in passing a married women’s property law in Illinois. This was a personal fight: the right of a married woman to retain custody of her children and her property. After nine years, she finally won custody of her now teenaged children. In the summer of 1869, Elizabeth gathered together and celebrated at the house she had bought in Chicago with earnings from her books.

After her children were grown, Packard went back to lobbying for people locked up in mental wards. She got a bill passed in Iowa, then in New York. Connecticut followed. Maine was a tougher nut to crack, and so she switched tactics. She decided to go to the federal level and went to Washington, DC.

First, she won over First Lady Julia Grant, then President Grant, and worked on a federal bill with feminist lawyer Belva Lockwood, the first woman to argue before the Supreme Court. The bill was passed.

Traveling by railroad, Packard spent the following fifteen years organizing in 25 other states. She was able to use her influence to change the laws changed in many of those states, with a greater emphasis on rights of the “insane” as the years went by.

Elizabeth Packard died July 25, 1897, at age 80.

Packard’s life demonstrates how dissonant streams of American society led to conflict between the freethinking Packard, her Calvinist husband, her asylum doctor, and America’s fledgling psychiatric profession. It is this conflict – along with her personal battle to transcend the stigma of insanity and regain custody of her children – that makes Elizabeth Packard’s story worthy of being told.

SOURCE

Elizabeth Packard Biography

Wikipedia: Elizabeth Packard

Encyclopedia.com: Packard v. Packard

Elizabeth Packard’s Fight to Overturn Legal Tyranny of Husbands