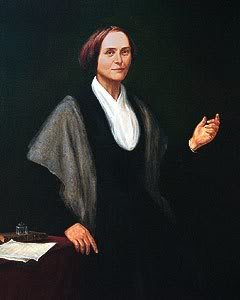

Editor of the First Feminist Periodical, The Una

Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis (1813–1876) was an abolitionist and feminist whose work in social reform extended over forty years. A wealthy and independent woman, she organized the First National Women’s Rights Convention in 1850, and another on the 20th anniversay of that occasion, at which she read from her written work, A History of the National Woman’s Rights Movement (1871).

Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis (1813–1876) was an abolitionist and feminist whose work in social reform extended over forty years. A wealthy and independent woman, she organized the First National Women’s Rights Convention in 1850, and another on the 20th anniversay of that occasion, at which she read from her written work, A History of the National Woman’s Rights Movement (1871).

Early Years

Paulina Kellogg was born on August 7, 1813 in Bloomfield, New York to Captain Ebenezer Kellogg and Polly Saxton Kellogg. The family moved to the frontier near Niagara Falls in 1817. Both of her parents died, and in 1820 Paulina went to live with a strict orthodox Presbyterian aunt in LeRoy, New York, where she was educated and attended church regularly.

Under her aunt’s influence, Paulina joined the church. She embraced religion, but suffered from thoughts of damnation and chafed at the church’s hostility toward outspoken women. She wanted to become a missionary but the church did not allow single women to become missionaries.

Paulina was courted by Francis Wright, a wealthy merchant from a prominent family in Utica, New York; they married in 1833, but had no children. They had similar values and both were involved in various reform movements – anti-slavery, temperance and women’s rights. Wright shared Davis’ passion for these causes, and joined his resources and executive ability with Paulina’s managerial skills and enthusiasm.

Career in Reform

In the late 1830s, Paulina met feminists Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Ernestine Rose. Although her husband forbade her to speak in public, she worked with Rose on a petition to the New York state legislature that eventually led to the passage of the Married Women’s Property Act in 1848, giving married women control of their own personal property and real estate.

Her husband’s death in 1845 left Davis desolate but independently wealthy and free to embark on a career as a lecturer and educator. She moved to New York City and studied the anatomy and physiology of women. In 1846 she imported a medical mannequin and began a series of lectures in anatomy, for women only, that would last for several years.

She toured the eastern United States with the mannequin to demonstrate the female physiognomy, educating women about their bodies and urging them to become physicians. The mannequin’s unveiling shocked some women, but others embraced the cause and became pioneer doctors. Davis’ new expertise led Abby Kelley to insist that she assist during the birth of her first child.

In the late 1840s Paulina met widower Thomas Davis, an antislavery Democrat, from Providence, Rhode Island. Davis had immigrated to the United States from Ireland in 1817, and his first wife Eliza Chace was a close friend of abolitionists Helen and William Lloyd Garrison.

Paulina Wright married Thomas Davis in April 1849 and they adopted two daughters together. A successful jeweler, Thomas Davis was also public spirited, and he supported many of Paulina’s causes, including women’s equality in marriage. He served in the Rhode Island State Senate from 1845 to 1853.

National Women’s Rights Conventions

In May 1850 a meeting was held to plan for the First National Women’s Rights Convention – two years after Seneca Falls – to be held on October 23-24 in Worcester, Massachusetts. Lucy Stone intended to spend the summer in Providence, working with Paulina on the details of the meeting. However, Stone was soon called away to Illinois to care for her sick brother. (Stone almost died of typhoid fever, and barely made it back in time for the convention.)

Paulina Wright Davis discontinued her lectures on anatomy and carried the full burden of planning the convention. She became organizer and president of the 1850 national convention. In the keynote address, Davis called for “the emancipation of a class, the redemption of half the world, and a conforming re-organization of all social, political and industrial interests and institutions.”

For two days, more than 1000 delegates from 11 states filled Brinley Hall to overflowing. Speakers, most of them women, demanded the right to vote, to own property, and to be admitted to higher education, medicine, the ministry and other professions. Although it was negative, press coverage of the convention helped bring it to the attention of a broad national audience and build support for the movement.

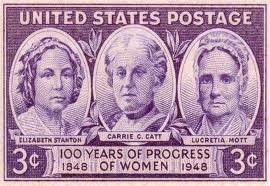

At the end of the convention, the participants insured annual national meetings by appointing a central committee, including Davis, William Henry Channing, Samuel May, Lucretia Mott, Wendell Phillips, Ernestine Rose and others, to coordinate efforts and call conventions. The changing members of this central committee served the movement throughout the decade.

The Second National Women’s Rights Convention was again held in Worcester, Massachusetts on October 15-16, 1851 and again presided over by Davis, drew a larger audience than the first. Committees appointed the previous year reported on women’s access to paid labor, education, political rights and social equality. Prominent women’s rights supporters, including Antoinette Brown Blackwell and Elizabeth Oakes Smith gave speeches.

Davis contributed to and attended but did not preside over the Third National Women’s Rights Convention held in Syracuse, New York on September 8-10, 1852. There were additional annual national conventions held from 1853 through 1860. The Civil War brought an end to the annual Women’s Rights Conventions, as women turned their hands to support emancipation and the northern war effort.

Davis was a daring but respected leader in the women’s rights movement whose intelligence, dedication, organizational skills and her wealth enabled her to make a significant contribution to the cause of women’s rights. Through the national conventions she organized and through her publications she informed people about ways to organize for much needed reforms.

In February 1853, Davis launched The Una, the first feminist periodical that was owned, written, edited and published entirely by a woman. The purpose was to “discuss the rights, sphere, duty and destiny of woman, fully and fearlessly.” Davis was determined to provide a source for written dialogue between women on the subject of labor, marriage, suffrage and schooling, and to demand that women enjoy more job opportunities and better pay. Davis was the paper’s chief author.

As she wrote in September 1853, “whoever can pay for himself and support himself will be free.” She solicited articles from feminist and social scientist Caroline Healey Dall and other prominent women reformers. This entertaining and instructive periodical, infused with feminist mottoes from philosophers, provides a unique window on the world of women in the 1850s.

Thomas Davis served in the United States Congress from March 4, 1853 through March 3, 1855. After moving to Washington, DC with her husband, Paulina Davis continued to edit The Una. However, a year later she invited Dall to share editorial responsibilities, and the magazine’s editorial office was transferred to Boston. Dall’s wish to make The Una a literary magazine clashed with Davis’ vision of it as an organ for reform. Within a year the publication collapsed.

Thomas Davis was not re-elected and he and Paulina returned to Providence, Rhode Island, where he resumed his jewelry business, and she continued to agitate for women’s rights. She broke with her old abolitionist friends and joined Elizabeth Cady Stanton to promote women’s suffrage over that of male African Americans.

After returning to Providence in 1855, the Davises lived in a spacious house surrounded by an extensive lawn and grand old trees, one and a half miles from town. Here Paulina Davis resided as a sort of foreign princess in Providence. She avoided isolation by importing artists and reformers. Her visitors included poet Walt Whitman, who enjoyed her hospitality, conversation and free spirit.

Late Years

After the Civil War, Paulina Wright Davis helped found the New England Woman Suffrage Association. Beginning in 1869 she made many of the arrangements for the twentieth anniversary of the First National Women’s Rights Convention, which was held at the Apollo Hall in New York City on October 21, 1870.

On that occasion, Elizabeth Cady Stanton stated that after due consultation the committee had decided that as Davis had called the first National Convention twenty years ago, and presided over its deliberations, it was peculiarly fitting that she should preside over this also. A motion was made and seconded to that effect, and unanimously adopted.

On taking the chair, Paulina Wright Davis read from her work, A History of the National Woman’s Rights Movement, which she published in 1871. This is an excerpt from that reading:

In assembling as we have done to review the past twenty years, it is a fitting question to ask if there has been progress; or has this universal radical reform, which was then declared, been like reformations in religion, but the substitution of a new error for an old one…

In commencing this work we knew that we were attacking the strongholds of prejudice, but truth could no longer be suppressed, nor principles hidden… We believed it would take a generation to clear away the rubbish, to uproot the theories of ages, to overthrow customs… We knew that in attacking these strongholds we should bring ridicule and opposition, but having counted the cost, and put our hand to the plow, we would not turn back…

Were I to go back of these [previous women’s rights] conventions, to see what had roused women thus to do and dare, I should be obliged to go into a long history of the despotism of repression, which German jurists call soul murder; an unwritten code, universal and cruel as the laws of Draco, and so subtle that, entering everywhere, they weigh most heavily where least seen.

During the 1860s and 1870s Davis traveled abroad with her adopted daughter and a niece. She met many prominent European reformers and indulged her love of art by copying the paintings of great masters. She abandoned her artwork when she became crippled with arthritis during the 1870s.

Paulina Wright Davis died on August 24, 1876 at her home in Providence, Rhode Island at age 63. At her funeral Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony eulogized Davis and urged others to follow her lifelong example of service to women.

Paulina Wright Davis was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 2002

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis

American National Biography: Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis

National Women’s Hall of Fame: Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis